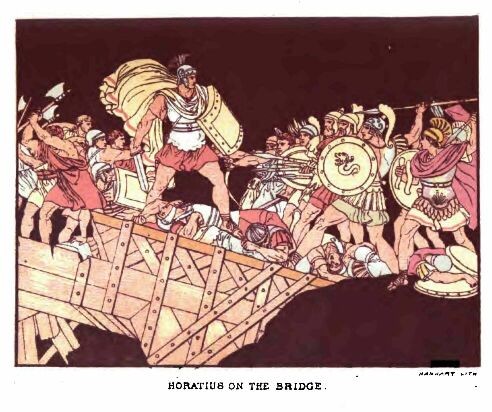

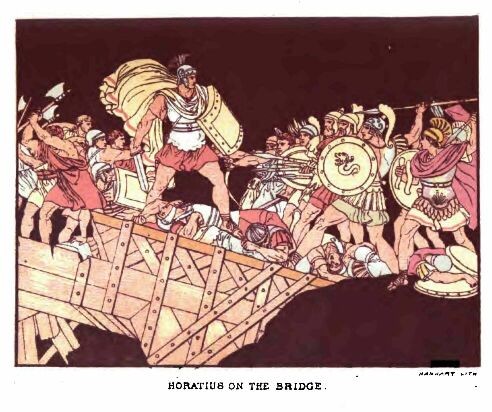

[Illustration: Horatius on the Bridge 126]

Prev | Next | Roman Legends from Livy | Main Page

[Illustration: Horatius on the Bridge 126]

King Tarquin and his son Lucius (for he only remained to him of the three) fled to Lars Porsenna, king of Clusium, and besought him that he would help them. "Suffer not," they said, "that we, who are Tuscans by birth, should remain any more in poverty and exile. And take heed also to thyself and thine own kingdom if thou permit this new fashion of driving forth kings to go unpunished. For surely there is that in freedom which men greatly desire, and if they that be kings defend not their dignity as stoutly as others seek to overthrow it, then shall the highest be made even as the lowest, and there shall be an end of kingship, than which there is nothing more honourable under heaven." With these words they persuaded King Porsenna, who judging it well for the Etrurians that there should be a king at Rome, and that king an Etrurian by birth, gathered together a great army and came up against Rome. But when men heard of his coming, so mighty a city was Clusium in those days, and so great the fame of King Porsenna, there was such fear as had never been before. Nevertheless they were steadfastly purposed to hold out. And first all that were in the country fled into the city, and round about the city they set guards to keep it, part thereof being defended by walls, and part, for so it seemed, being made safe by the river. But here a great peril had well nigh overtaken the city; for there was a wooden bridge on the river by which the enemy had crossed but for the courage of a certain Horatius Cocles. The matter fell out in this wise.

There was a certain hill which men called Janiculum on the side of the river, and this hill King Porsenna took by a sudden attack. Which when Horatius saw (for he chanced to have been set to guard the bridge, and saw also how the enemy were running at full speed to the place, and how the Romans were fleeing in confusion and threw away their arms as they ran), he cried with a loud voice, "Men of Rome, it is to no purpose that ye thus leave your post and flee, for if ye leave this bridge behind you for men to pass over, ye shall soon find that ye have more enemies in your city than in Janiculum. Do ye therefore break it down with axe and fire as best ye can. In the meanwhile I, so far as one man may do, will stay the enemy." And as he spake he ran forward to the further end of the bridge and made ready to keep the way against the enemy. Nevertheless there stood two with him, Lartius and Herminius by name, men of noble birth both of them and of great renown in arms. So these three for a while stayed the first onset of the enemy; and the men of Rome meanwhile brake down the bridge. And when there was but a small part remaining, and they that brake it down called to the three that they should come back, Horatius bade Lartius and Herminius return, but he himself remained on the further side, turning his eyes full of wrath in threatening fashion on the princes of the Etrurians, and crying, "Dare ye now to fight with me? or why are ye thus come at the bidding of your master, King Porsenna, to rob others of the freedom that ye care not to have for yourselves?" For a while they delayed, looking each man to his neighbour, who should first deal with this champion of the Romans. Then, for very shame, they all ran forward, and raising a great shout, threw their javelins at him. These all he took upon his shield, nor stood the the less firmly in his place on the bridge, from which when they would have thrust him by force, of a sudden the men of Rome raised a great shout, for the bridge was now altogether broken down, and fell with a great crash into the river. And as the enemy stayed a while for fear, Horatius turned him to the river and said, "O Father Tiber, I beseech thee this day with all reverence that thou kindly receive this soldier and his arms." And as he spake he leapt with all his arms into the river and swam across to his own people, and though many javelins of the enemy fell about him, he was not one whit hurt.

[Illustration: Horatius on the Bridge 126]

Nor did such valour fail to receive due honour from the city. For the citizens set up a statue of Horatius in the market-place; and they gave him of the public land so much as he could plough about in one day. Also there was this honour paid him, that each citizen took somewhat of his own store and gave it to him, for food was scarce in the city by reason of the siege.

After these things King Porsenna thought not any more to take the city by assault, but rather to shut it up. To this end he held Janiculum with a garrison, and pitched his own camp on the plain ground by the river; and the river he kept with ships, lest food should be brought into the city by water. Thus it came to pass in no long time that the famine in the city was scarcely to be endured, so that the King had good hopes that the Romans would surrender themselves to him. But being in these straits, they were delivered by the boldness of a noble youth, whose name was Caius Mucius. This man at the first purposed with himself to make his way into the camp of the enemy without the knowledge of any; but fearing lest if he should go without bidding from the Consuls, no man knowing his purpose, he might haply be taken by the sentinels and carried back to the city as one that sought to desert to the enemy--Rome being in so evil a plight that such an accusation would be readily believed--he sought audience of the Senate. And being admitted he said, "Fathers, I purpose to cross the Tiber, and to enter, if I shall be able, the camp of the enemy; plunder I seek not, but have some greater purpose in my heart." So the Fathers giving their consent, he hid a dagger under his garment and set forth; and having made his way into the camp, he took his stand where the crowd was thickest, hard by the judgment-seat of the King. Now it chanced that the soldiers were receiving their wages. There sat by the King's side a scribe, and the man wore garments like unto the King's garments. And Mucius, seeing that the man was busy about many things, and that the soldiers for the most part spake with him rather than with the other, and fearing to ask which of the two might be the King, lest he should so show himself to be a stranger, left the matter to chance, and slew the scribe. Then he turned to flee, making a way for himself through the crowd with his bloody sword; but the ministers of the King laid hands on him, and set him before the judgment-seat. Thereupon he cried, "I am a citizen of Rome, and men call me Caius Mucius. Thou art my enemy, O King, and I sought to slay thee; and now, as I feared not to smite, so I fear not to die. We men of Rome have courage both to do and to suffer. Think not that I only have this purpose against thee; there are many coming after me that seek honour in this same fashion by slaying thee. Prepare thee, therefore, to stand in peril of thy life every hour, and know that thou hast an enemy waiting ever at thy door. The youth of Rome declares war against thee, and this war it will wage, not by battle, but by such deeds as I would have done this day."

[Illustration: Mutius before King Porsenna 132]

King Porsenna, when he heard these words, was greatly moved both by wrath and by fear and bade them bring fire, as though he would have burned the young man alive, unless he should speedily reveal what that danger which he threatened against the King might be. Then said Mucius, "See now and learn how cheaply they hold their bodies that set great glory before their eyes," and he thrust his right hand into a fire that had been lighted for sacrifice. And as he stood and seemed to have no feeling of the pain, the King, greatly marvelling at the thing, leapt from his seat and bade them take, away the young man from the altar. "Depart thou hence," he cried, "for I see that thou darest even worse things against thyself than against me. I would bid thee go on and prosper with thy courage wert thou a friend and not an enemy. And now I send thee away free and unharmed." Then said Mucius, as though he would make due return for such favour, "Hearken, O King; seeing that thou canst pay due respect unto courage, I will tell thee freely that which thou couldst never have wrung from me by threats. Three hundred youths of Rome have banded themselves together with an oath that they will slay thee as I would have slain thee. And because the lot fell to me I came first of the three hundred, who all will follow, each in his own time, according as the lot shall fall."

So Mucius departed; and men called him thereafter Scævola, or the left-handed, because he had thus burned his right hand in the fire. No long time after there came ambassadors from King Porsenna to Rome, for the King was so moved not only by the peril that was past, but also by that which was to come, so long as any of the three hundred yet lived, that of his own accord he offered conditions of peace to the Romans. And in these conditions he made mention of bringing back the Tarquins, knowing indeed that the men of Rome would not allow it, but because he was under promise to make such demand. As to other matters, he required, the Romans consenting, that the land of the men of Veii should be given back to them, and he would have hostages given to him if he should take away his garrison from Janiculum.

To this also the Romans agreed by compulsion. So King Porsenna departed from Rome; and the Senate gave to Mucius certain lands beyond the Tiber that were called in time to come after his name.

And now were the women of Rome also stirred up to do bold deeds for their country. For a certain maiden, Cloelia by name, that was one of the hostages, the camp of the Etrurians having been pitched near unto the Tiber, escaped from them that kept her, and swam across the river, the whole troop of her companions following her. These she brought back to the city and delivered safe to their kinsfolk.

[Illustration: Cloelia and her companions 136]

News of this deed being brought to the King he was at the first moved to great wrath, and sent ambassadors to Rome who should demand the hostage Cloelia to be restored; as for the others he cared little for them; but afterwards, his wrath giving place to wonder, he cried, "Surely this deed is greater even than the keeping of the bridge by Horatius, or the burning of his right hand by Scævola. As for the treaty, I shall hold it to be broken if the Romans give not up the hostage; but if she be given up I will send her back unharmed to her own kindred." And so indeed it was done, both parties keeping faith, for the Romans gave up Cloelia as the treaty commanded, and the King judged valour to be worthy not of safety alone but also of reward. "I will give thee," he said to her, "a certain portion of the hostages: thou shalt choose whom thou wilt." Then she chose such as were of tender age, not only because this best became the modesty of a maiden, but because such would be in the greater peril of harm. To her the Romans set up in the Sacred Road a statue, a maiden sitting on horseback--a new honour, even as the valour that was so honoured was new also.

So King Porsenna departed from Rome, and departing gave his camp, that was full of all manner of good things, to the men of Rome, there being great scarcity in the city by reason of the length of the siege. In the next year he sent ambassadors yet once again who should deal with the people of Rome about the bringing back of the King. To them was given this answer, "that the Senators would send ambassadors about the matter." These ambassadors, who were the chiefest men in the city, being arrived, spake in this fashion: "We might have answered thy ambassadors, O King, in very few words, saying that we take not back the King. But we are come this day that there may never again be made mention of this matter, lest there come out of it trouble both to thee and to us, if thou shouldst ask that which would be against the liberty of the Roman people, and we should be driven to refuse something to thee who would gladly refuse thee nothing. The men of Rome are free and serve not kings, and verily they would the sooner open their gates to their enemies than to kings. And this is the mind of us all. That day which shall make an end of our freedom shall make an end also of our city. If therefore thou wouldst have us live, suffer us, we pray thee, to be free."

To this the King made answer in these words: "I will weary you no more by asking that which ye may not grant, nor will I deceive the Tarquins by show of help that it is not in me to give. As for them, whether they be minded to have peace or war, let them seek for another place of exile, that there come not anything to make mischief between you and me."

To these words he added much kindness in deeds, for he gave back such of the hostages as yet remained with him; also he restored to the Romans the land of the men of Veii that had been taken from them by the treaty of Janiculum.

After this, King Tarquin took up his abode with Mamilius Octavius, his son-in-law, that dwelt at Tusculum. And Mamilius stirred up the thirty cities of Latium to make war against Rome. For five years he made great preparations, and in the sixth year he set forth. And when the Romans knew of his coming, they made Aulus Postumius Dictator. Now a dictator was one that had the power, as it were, of a king in the city, only he might not remain for a greater space than six months. And Postumius chose Æbutius to be Master of the Horse, for the Master of the Horse is next under the Dictator. These, having gathered together their army, marched forth' and met the Latins hard by the Lake Regillus that is in the land of Tusculum. And so soon as the Romans knew that King Tarquin was in the army of the Latins, they were full of wrath and would fight without more delay. Nor indeed was ever battle harder and fiercer than this; for the chiefs contented themselves not with giving counsel how it might best be ordered, but themselves fought together, so that scarce one of them, save the Dictator only, came out of the battle unhurt. First of all King Tarquin, for all that he was an old man whose force was somewhat abated, when he saw the Dictator in the front ranks setting his men in order and bidding them be of good cheer, set spurs to his horse and rode against him; but some one smote him on the side as he rode. Nevertheless, his own men running about him, he was carried back alive into the host. On the other wing the Master of the Horse made at Mamilius, prince of Tusculum. And when Mamilius saw him coming he also spurred his horse against him, and the two came together with so great force that Mamilius was wounded in the breast, and Æbutius was smitten through the arm. Then the Master of the Horse, because his right arm was wounded, and he could not hold a weapon in it, departed from the battle, but Mamilius, caring nought for his wound, still stirred up the Latins to fight; and because he perceived them to be somewhat troubled with fear, he bade advance the company of exiles that had gone forth from Rome with King Tarquin. Very fiercely did they fight, as men that had been spoiled both of goods and country, and bare back the Romans a space. And when Valerius that was brother to Publicola (than whom none but Brutus only had been more zealous in driving out the King) saw the King's son among the foremost of the exiles, he set spurs to his horse and made at him with his spear. Nor did the young Tarquin abide his coming, but turned his back, hiding himself in the company of the exiles; and as Valerius pursued him and rode, taking no thought of what he did, into the very ranks of the enemy, one smote him upon the side so that he fell from his horse dying. And when the Dictator saw that so brave a champion was dead, and that the exiles were pressing on more fiercely and that the Romans gave place in great fear, he cried to the company that followed him, "See that ye deal with any Roman that ye see fleeing as with an enemy." Then they that fled, seeing this peril behind them, stayed their steps and addressed themselves again to the battle. But when Mamilius saw that the company of exiles was well nigh surrounded by the Dictator and his men (for these were fresh and vigorous), he brought up sundry companies from the reserve, and would have assailed them. But Herminius, the same that kept the bridge over Tiber along with Horatius against the army of King Porsenna, espied him coming, and knew him for the Chief by his garments. He made at him with all his might, and with one blow smote him through the side and slew him. But while he stripped the body of its armour one of the Latins thrust at him with a spear, and hurt him that he fell to the earth. Men carried him back to the camp, but when they would have tended his wound he died. Then the Dictator cried to the horsemen that followed him, "See now how the foot soldiers are wearied out. Leap down therefore from off your horses, and fight on foot." And when the foot soldiers saw them leap down, they took courage again, and made forward against the Latins; and these, after a while, turned their backs and fled. Then the Dictator bade them bring again their horses for the horsemen, that they might the more conveniently pursue the enemy. Also, that no help either from god or man might be wanting, he made a vow to the Twin Brethren that he would build them a temple, and he proclaimed that he would give rewards, one to him who should be first in the camp of the enemy, and another to him who should be second. So great, indeed, was the courage of the soldiers that they took the camp of the Latins that very same hour. Thus did the men of Rome put the Latins to flight at the Lake Regillus, and the Dictator with the Master of the Horse returned in great triumph to Rome.

Prev | Next | Roman Legends | Main Page