Prev

| Next

| Contents

GOOD WOMEN OF NERO'S REIGN

The immoralities which characterized the reigns of some of the first

emperors must be considered as abnormal outbreaks rather than as

permanent conditions. The element of corruption is always present in the

social body. As a rule, it reveals itself only to those who look for it

in the slums and prisons and criminal haunts, but at times and under

certain conditions it breaks out with excessive virulence, and, to adopt

a Biblical figure, there seems to be no soundness in the whole body.

Such conditions were present during the period we have been studying.

Many circumstances combined to bring all the corruption and immorality

which are usually veiled or disguised into prominent view and to make

them fashionable. The accidents of birth placed upon the imperial throne

men who were morally insane; consequently, the evil-disposed found

themselves in a paradise of crime, while the ambitious, the covetous,

and the cowardly were enabled to gain their ends and preserve their

safety only by becoming caterers to and companions in their masters'

lusts.

It is very easy, however, for a student of history to encourage an

exaggerated idea of Roman depravity, even as it was in the days of

Messalina and Poppsea. Whence do we obtain our picture of the Rome of

those times? Partly from historians; but very largely from such writers

as Juvenal, Petronius, and Apuleius. The historians confined their

accounts to the prominent people of their times, and it not unfrequently

happened that the most prominent and successful were the least

commendable from the moral standpoint. The moralists necessarily placed

the worst in the boldest relief, in order to ensure a more telling

effect. Seneca held such writers up to ridicule, when he said: "Morals

are gone; evil triumphs; all virtue, all justice, is disappearing; the

world is degenerating. This is what was said in our fathers' days, it is

what men say to-day, and it will be the cry of our children." And yet,

the world does not grow worse. As for the society portrayed by Petronius

and Apuleius, these men sought their characters among the low pothouses

and the brothels of Rome. The morals of the ordinary Roman home must not

be judged by a scene either in a house of ill fame or in the palace of a

crazy and dissolute tyrant, any more than the common life of Herculaneum

or Pompeii is to be conjectured solely from the obscene pictures found

on the walls of their ruined dwellings.

In this present chapter, the women we shall cite are chiefly those who

were ennobled in their deaths rather than in their lives. That is to

say, though they lived well, had it not been for their brave manner of

dying their names would not have been preserved in history.

As has been said, Roman society was not wholly corrupt, even though an

adulterous Messalina, an unprincipled Poppæa, or a cruel and ambitious

Agrippina, shared the throne. Contemporary with these were women who

still with pure hands and sincere hearts invoked the ancient goddess of

chastity. There were those who had mother love for their children, but

were free from deadly ambition. Among the more ordinary homes were many

that were graced with the same family loyalty and tender affection as

beautify our homes to-day.

The young women of the days of Claudius were not obliged to search in

the musty annals of past times for examples of feminine honor and

virtue. They had all known Antonia, the virtuous daughter of Octavia and

Antony, who, like Agrippina, had honored her widowhood by a long and

irreproachable chastity. Yet the maidens of Messalina's age may have

been the less attracted by the example of Antonia because, while she

retained the old Roman purity of morals, she also exemplified the old

Roman severity of manners. Claudius, her son, never ceased to stand in

awe of her, and during his childhood her severity to him was such that

it is supposed that it helped to induce his imbecility. When her

daughter Livilla had been betrayed into crime by means of the arts of

Sejanus, Antonia was even more inexorable than Tiberius, against whom

the plot had been laid, and she caused the young woman to be starved to

death. It was not an instance of cruelty, it was simply the old Roman

justice, in which personal or even maternal feeling was allowed no

place. Antonia's goodness was not of the attractive kind. We must

imagine her as a proud, puritanical old matron, who made herself a

terror to wrong doers. She courageously rebuked her grandson Caligula

for his enormities; but the young ruffian, who possessed neither the

mind nor the conscience to respect age or kinship, in return caused

Antonia to be put to death--though it is possible that the actual deed

may have been her own.

It was asked of old: "Can a clean thing come out of an unclean?" The

affirmative answer to this question is found in the person and character

of Octavia, the daughter of Messalina the infamous. Indeed, the axiom

that "like produces like" cannot be applied to moral character; so many

instances are met with of bad offspring from noble parentage and

virtuous children from immoral antecedents that they cannot be regarded

as exceptions to the rule.

Octavia was fortunate in nothing but her character. She was the

plaything of a relentlessly adverse fate. The whole of her short life is

an illustration of the fact that goodness of disposition does not

protect its possessor from the worst evils of existence. That this young

girl remained virtuous amid the whirl of immorality in which she was

reared, with no lovable example and no motherly advice, is a proof of

the invincibility of a good disposition if nature has woven it into a

human character.

As a little child, Octavia had been petted and fondled by her father,

the poor old Emperor Claudius, who, dull and phlegmatic as he was, would

have been a good-hearted man if he had not been thrust into a position

for which he was totally unfitted. He loved to take Octavia and her

little brother Britannicus to the theatre and hold them with a father's

pride before the admiring eyes of the people. This was all the love that

Octavia ever knew. One of her earliest and saddest experiences was to be

sent by Messalina out upon the road to Ostia, to meet Claudius and plead

vainly for that unworthy mother's life. Then Agrippina came to the

palace; and with her in the double capacity of empress and stepmother,

Octavia found no cause of thankfulness for the change. Hitherto she at

least had not been used as a mere tool to effect some other's political

ambitions. Her father Claudius had betrothed her to Lucius Silanus, a

celebrated and favorite Senator. Had this match been allowed to remain

undisturbed, it is possible that Octavia's lot might have been peaceful

and happy; but a false charge against Silanus was trumped up by the

perfidious Vitellius, so that the former was degraded from the Senate,

and immediately afterward he committed suicide, Octavia lived on and

encountered the terrible misfortune of being betrothed to Nero, whom

Seneca was advising to "compensate himself with the pleasures of youth

without compunction." Agrippina threw Octavia to her son, just as a rope

might be tossed to a mountain climber to enable him to ascend a

difficult pass; when its use has been served, it is looked upon as a

piece of mere cumbersome baggage. So Nero considered his wife, after he

had obtained the Empire. When he expressed his dislike for her, the

plain-spoken Burrhus said: "Very well, send her away; but of course you

will give up her dower with her;" which was nothing less than the throne

of Claudius.

Had Octavia been supported by some all-powerful and sympathetic relative

like Augustus, she might have survived and have shown as great patience

with the vices of Nero as her ancestral namesake showed with those of

Antony; but she was left unprotected amidst numerous opposing forces

which, when not aimed with deadly hatred against her, were indifferent

to her welfare, with the consequence that she was speedily and

mercilessly crushed.

The first woman who took the place which Octavia never held in Nero's

affections was the Greek freedwoman Acte. The wild young emperor would

have divorced his wife and married the Greek forthwith, but he was still

under the domination of the powerful Agrippina. This first thwarting of

the imperial will was the beginning of Agrippina's downfall. It was not

long before she and the young wife saw a fearful presage of their own

fate when the young Britannicus fell dead upon the banquet floor,

poisoned by the diabolical art of Nero's instrument, Locusta. Octavia,

though so young, was not entirely ignorant as to what the perils of her

situation demanded. She had received early lessons in a terrible school.

Consequently, when Nero declared to the alarmed guests that her brother

was habitually afflicted with the falling sickness, she disguised her

sisterly grief and composedly retained her place at the banquet.

But the time came when Agrippina had also fallen a victim to her son's

inhumanity, and Nero, responsible to no human being, had become enamored

by the more attractive fascinations of a more unprincipled woman than

Acte. "Why does not Nero," the tyrant asks of himself, "banishing all

fear, set about expediting his marriage with Poppæa? Why not put away

his wife Octavia, although her conduct is that of a modest woman, since

the name of her father and the affection of the people have made her an

eyesore to him?" With Poppæa urging him on and the villainous Tigellinus

exercising his diabolical ingenuity to find a plausible excuse, it was

not long before the courage of Nero was equal to the audacious act of

driving from the imperial palace the woman through connection with whom

he had his right of tenure there. Octavia was divorced by process of

law, under the allegation that she was barren. At first she was awarded

the house of Burrhus and the estate of Plautus, whom Nero had recently

put to death. The divorce being sought by her husband for no fault of

hers, he was obliged, if the strict letter of the law had been observed,

to give up with her the whole of her dowry; but for men like Nero, who

execute the laws, a mere pretence of legality suffices. Poppæa had

brazenly endeavored to trump up a far more serious charge against the

woman she injured; but it could not be made to hold. She bribed one of

Octavia's domestics to assert that her mistress had participated in an

amour with Eucerus, an Alexandrian flute player; but this accusation was

so preposterously inconsistent with Octavia's well-known character that,

even though they tortured her servants, they could gain no evidence

which they dared to set before the people in substantiation of the

charge. There could be no stronger testimony to the amiability and

lovableness of Octavia, as well as to the purity of her character, than

the fidelity with which her servants defended her reputation from all

aspersions, even while they were undergoing the most intense torture.

One brave maid, while being examined upon the rack, spat in the face of

Tigellinus, who was urging a confession, and declared aloud that "the

womb of Octavia was purer than his mouth." It was among slaves like

these that the first Christian martyrs were found; women who gave their

bodies to the most excruciating torture, but could not be induced to

deny their faith.

Soon after Octavia's divorce, she was banished into Campania, where she

was kept in close confinement, and a guard of soldiers was placed over

her. But though the Senate and the nobility had become absolutely

enslaved to the imperial tyrant's will, there was always the people to

reckon with. The common women talked loudly but sympathetically of

Octavia's persecuted innocence. The men took up the cry; they made it

heard in the theatre and they scribbled it upon the walls. The people

could not be individualized. They had not but one neck, as Caligula had

so maliciously wished. Their number and individual insignificance

rendered it possible for them to express their mind with impunity. Nero

hastened to recall Octavia to the city.

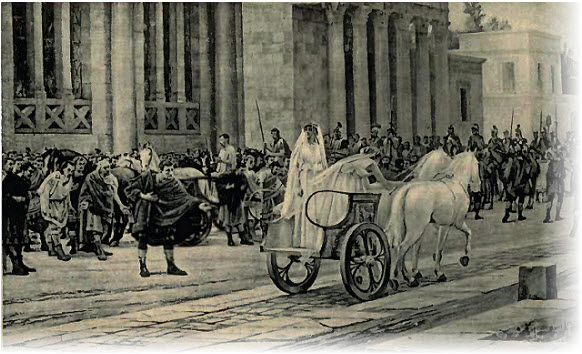

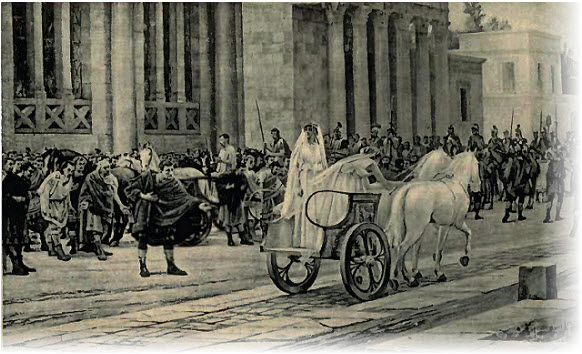

That was a day of proud but dangerous joy for the unfortunate young

empress. At least she had the satisfaction of knowing that all the world

believed in her innocence. In their happiness, the multitude went to the

Capitol and thanked all the gods for her return. They threw down the

statues of Poppæa, and wherever they could find one of Octavia they

wreathed It with flowers and removed it to the Forum or to some temple.

They even went to the palace to applaud Nero for bringing back his

banished wife, but were driven thence by the soldiery.

AH this served only to incite Poppæa to take the most desperate

measures. She approached Nero with such artful insinuations in regard to

the possibility of the people's revolting in favor of Octavia, and at

the same time with a pretence of such meek submissiveness in regard to

her own personal fortunes, that the emperor was induced both by fear and

passion to take the course which she desired.

A method of getting rid of Octavia without incurring danger was not easy

to devise; but Nero had at his court a man who was a genius in the art

of removing formidable impediments. Anicetus had proved his ability upon

Agrippina. He was not only resourceful, but absolutely without either

honor or conscience. It was not alone necessary that Octavia should be

destroyed, but her death must take on the semblance of a justified

punishment. There was none who could or would testify aught against her.

Nero summoned Anicetus and told him "that he alone had saved the life of

his prince from the dark devices of his mother; now an opportunity for a

service of no less magnitude presented itself, by relieving him from a

wife who was his mortal enemy. There was no need of force or arms; he

had only to admit of adultery with Octavia!" The dastardly freedman

forthwith began to boast among his friends of the favors he received

from the young empress. On being summoned to a council of the friends of

Nero, he made a pretended confession. He was condemned to banishment to

Sardinia, where he lived in great luxury until he died a natural death.

Nero published an edict in which he stated that Octavia had been

discovered seeking, through the corruption of Anicetus, the admiral, to

engage the fleet in a conspiracy, and that her infidelity was clearly

proved. Octavia was sent to the island of Pandataria. Tacitus says:

"Never was there any exile who touched the hearts of the beholders with

deeper compassion. Some there were who still remembered to have seen

Agrippina the Elder banished by Tiberius; the more recent sufferings of

Julia were likewise recalled to mind--that Julia who had been confined

there by Claudius. But they had experienced some happiness, and the

recollection of their former splendor proved some alleviation of their

present horrors." Everything in Octavia's life that promised pleasure

had been turned to gall. Her home recalled the scenes of her father's

poisoning and her brother's murder; her marriage rights had been first

usurped by a handmaid and then by a woman known to be of infamous

character; and now even her memory was to be stained with the imputation

of a crime which was more intolerable to her than death itself. There is

no sadder picture in all history than that of this girl,--she was only

twenty,--after her short life of uninterrupted sorrow and unstained

innocence, thrown among centurions and common soldiers, who dared not

help her even if a feeling of pity entered their hearts. They commanded

her to die; but she had not the strength or the courage of Antonia. She

pleaded that she was now a widow, and that the emperor's object having

been gained he had no cause to fear anything from her. She invoked the

name of Agrippina, and said "that had she lived, her marriage would have

been made no less wretched, but she would not have been doomed to

destruction." When those in charge saw that it was hopeless to expect

that she would take the unpleasant task off their hands, they bound her

and opened her veins; but, the blood flowing too slowly, her death was

accelerated by the vapor of a bath heated to the highest point. After

life was extinct, they severed her head from her body and carried it to

Poppaea, in order that she might see that the deed by which she was made

Empress of Rome was surely accomplished.

The abject Senate, when they learned that the whole matter was thus

concluded, decreed that offerings should be made at the temples, as a

thanksgiving for the deliverance of the emperor from the dangers which

had threatened him through the conspiracy of his wife. Tacitus declares

that he records this circumstance "in order that all those who shall

read the calamities of those times, as they are delivered by me or any

other authors, may conclude, by anticipation, that as often as a

banishment or a murder was perpetrated by the prince's orders, so often

thanks were offered to the gods; and those acts which in former times

were resorted to in order that prosperous occurrences might be

distinguished, were now made the tokens of public disasters."

These were the days of the martyrs. During this reign, the burning

bodies of Christians lighted the gardens of the malevolent tyrant,

innocent women and tender girls were exposed to fierce beasts in the

arena, and by their sufferings were made to contribute interest to a

Roman holiday. These died for their faith. They died gladly, in the

belief that their pains and faithfulness were to be rewarded with an

unfading crown in a land beyond the skies. They cheered each other in

the face of death, and they were comforted by those friends who were

still at liberty with the promise of a meeting where no tyrant's hand

could harm them. Octavia was not of this faith. It is probable that she

knew nothing of the strange doctrines which were making converts among

the Roman slaves. Yet there was no martyr more innocent than herself,

none more worthy of canonization. There was none whose purity and whose

fidelity to the principles which were cherished by high souls could

present a better claim for the victor's palm and the martyr's crown than

her own. Octavia knew nothing of the Christian hope of immortality; her

religious faith at the best could teach her no more than the vague

surmise that possibly in some dreary under world the shades of mortals

retained a melancholy consciousness. Yet a consistent justice at the

present day cannot do other than place side by side the persecuted girl

from the imperial palace and the Christian slave maiden whose blood

dripped from the jaws of the beasts of the arena, and believe that

whatever consolation eternal fate provided for the one was equally

shared in by the other.

As we have said, the first woman to attract the affections of Nero,

which were never turned toward Octavia, was Acte. She had probably been

brought as a slave from Asia. How old she was when Nero first knew her

it is impossible for us to conjecture, but it is likely that she was

somewhat older than the youthful emperor; it frequently happens that a

boy's first love is aroused by a woman his superior in age. Then, too,

Acte was at this time a freedwoman. Liberty was often gained by female

slaves by means of the charms of their persons; but this result was not

likely to be secured before those charms were fully matured. So profound

was Nero's passion for Acte that, had he not been with difficulty

restrained, he would have divorced Octavia forthwith and married the

Greek. He is said to have induced men of consular rank to swear that she

was of royal descent. It is by no means impossible that such an

assertion should be true; for the slave markets which supplied Rome were

to a large extent recruited by kidnapped children, picked up wherever

they might be found. It is remarkable that not a word that is

detrimental to the character of Acte is recorded in history. Indeed, we

know but very little about her, though she has always been regarded with

a sort of poetical approbation. There is no evidence of her having used

her power with the emperor for the injury of an enemy. She seems to have

been modest and unassuming, and it is certain that her love for Nero was

sincere; for it not only outlasted his, but remained true to the latest

hour of his life. When all others had forsaken the fallen prince whom

they had fawned upon, it was Acte who tenderly cared for his remains.

Tacitus represents her as warning Nero from his early evil

extravagances. She remained queen of his affections for four years,--the

best four years of his reign,--and it is said that when he turned from

her to Poppaea she sank into a profound melancholy. Upon all this has

been founded the surmise that Acte was a Christian; but it is nothing

more than conjecture. Whatever may have been the facts in regard to

this, in the little glimpses we obtain of her presence in the awful

tragedies of her age we catch the outline of one whom we are assured

must have been a good woman--a woman innately pure, but forced into

contact with vice by circumstances over which she had no control.

There are numerous examples from history to prove that in the dissolute

reign of Nero feminine goodness was not a rarity; but there are no

pictures of pure light-heartedness and gladsome simplicity such as were

known in the older days. Everything was sombre; death was in the air;

the only gayety was that found in the scenes of reckless profligacy. It

was an age of extremes; on the one side, unrestrained profligacy; on the

other, fear and sorrow occasioned by a tyrant's cruel caprice. It was an

age in which all the experiences of life were intensified. Human life

of the period can only be pictured in high lights and deep shadows;

everything must be shown in strong relief. The fortune of nearly all the

good women of this time whose names we know was to suffer patiently and

die heroically.

Like Acte, the noble matron Pomponia Græcina has been credited by

tradition with having found consolation for the sorrows of the times in

that new faith which was undermining old Rome, both literally in the

catacombs and figuratively in the rapidity with which it was making

converts; but we know not with certainty. It would be unjust to paganism

and untrue to history to claim every instance of moral superiority for

the modern faith. Still, Græcina was accused of yielding to foreign

superstitions. This may have been owing to the peculiarities of her

manner. She had been the close friend of that Julia, daughter of Drusus,

whom Messalina had forced to kill herself. From this time on, for the

space of forty years, Græcina wore nothing but mourning, and was never

seen to smile. Sienkiewicz founds the plot of his Neronian novel on the

idea that Græcina was a Christian; but there are no facts by which this

supposition can be verified. When the charge of entertaining foreign

superstitions was laid against her, she was, in accordance with the

ancient law, consigned to the adjudication of her husband. Plautius

assembled her kindred, and, in compliance with the institutions of early

times, having in their presence made solemn inquisition into the

character and conduct of his wife, adjudged her innocent. She survived

to a great age and was always held in high estimation by the people, but

she never recovered from her melancholy.

When the noble Thrasea had been condemned to death by Nero, the officer

who brought the tidings found him walking in the portico of his house.

He had already opened his veins, and as he stretched out his arms the

blood began to flow. Calling the quæstor to him, and sprinkling the

blood upon the floor, he said: "Let us make a libation to Jove the

Deliverer. Behold, young man, and may the gods avert the omen, but you

are fallen upon such times that it may be useful to fortify your mind by

examples of unflinching firmness." Arria, his wife, wished to share her

husband's fate, but he bade her live for their daughter's sake.

There were many women who presented examples of the same unflinching

firmness for the encouragement of their own sex. The mother of Thrasea's

wife, whose name was also Arria, exhibited a strength of mind and a

magnanimity of spirit equal to that of the noblest Romans in the best

days of the Republic. Duruy recounts two episodes in the career of this

noble woman which illustrate all we have claimed for her as one of the

best of her sex.

"Arria's husband, Cæcina Pætus, and his son were affected with a serious

malady; the son died. His mother took such measures respecting the

funeral that the father knew nothing of it. Every time she entered his

room she gave him news of the sufferer,--he had not slept badly, or

perhaps he was recovering his appetite; and when she could no longer

restrain her tears she went out for a moment, and then returned with dry

eyes and a calm face, having left her grief behind her. At a later

period, her husband, being concerned in the conspiracy of Scribonianus,

was captured and taken to Rome. He was put on board a ship, and Arria

begged the soldiers to allow her to go with him, 'You cannot refuse,'

she said to them, 'to a man of consular rank a few slaves to wait on him

and dress him; I alone will do him these services.' As they continued

inexorable, she hired a fishing boat and followed across the Adriatic

the vessel in which her husband was conveyed. At Rome, she met the wife

of Scribonianus, who attempted to speak to her. 'How can I listen to

you,' she said to her, 'who have seen your husband killed in your arms,

and who are still alive?' Foreseeing the condemnation of Pætus, she

determined not to survive him. Thrasea, her son-in-law, begged her to

give up this determination. 'Is it your wish, then,' he said to her, 'if

I should be compelled to die, that your daughter should die with me?'

'If she shall have lived as long and as united a life with you as I with

Pætus, it is my wish,' was the reply. Her family watched her carefully,

to prevent her fatal design. 'You are wasting your time,' she said; 'you

will make me die a more painful death, but it is not in your power to

prevent me from dying.' Thereupon she dashed her head against the wall

with such violence that she fell down as if dead. When she recovered her

senses, she said to them: 'I have already warned you that I should find

some means of death, however hard, if you denied me an easy one.' We

cannot wonder that, to decide her hesitating husband, she struck herself

a fatal blow with a poniard; then handed him the weapon, saying: 'Pætus,

it gives no pain.'"

Pliny gives an account of an incident showing similar conjugal devotion

and self-sacrificing courage. "I was sailing lately," says he, "on our

Lake Larius, when an elderly friend pointed out to me a house, one of

whose rooms projected above the waves. 'From that spot,' he said, 'a

townswoman of ours threw herself out with her husband. The latter had

long been ill, suffering from an incurable ulcer. When she was convinced

that he could not recover from his disease, she exhorted him to kill

himself, and became his companion in death--nay, rather his example and

leader, for she tied her husband to her and jumped into the lake.'" This

was a woman of the common citizens; we do not even know her name.

Modern times have no examples to show of a closer marital sympathy than

this. Our ideas compel us to deprecate the act of self-destruction; but

we cannot question, or more than rival, such devotion. The like degree

of faithfulness between married couples was common among the Romans; and

this was their manner of showing it.

We have, more than once, seen the statement advanced in all seriousness

by well-informed writers and public speakers that marital affection, in

the modern understanding of the expression, was almost unknown among the

ancients. The object of the contention is to enhance the appreciation of

the effects of Christianity; but the argument is as absurdly

inconsistent with history as it is with common sense. True, Christianity

discourages conjugal unions in which that affection does not exist, but

it does not create it; nor was there anything whatever in pagan customs

or institutions to prevent the existence of the warmest and purest

affection between husband and wife. The sole conditions in the ancient

world that militated against pure and constant married love were the

customary unions of expediency and the inferior position of the wife. As

to the first of these customs, it is by no means unknown in the modern

world and to Christian times; in regard to the second, the Roman wife in

the period with which we are now engaged was almost equally as well off

as her modern descendant.

Principles of virtue, honor, and duty of a high order had been

inculcated through many generations of ancient Romans; and it could not

be otherwise than that these would reappear and manifest themselves with

invincible insistence, even in the most corrupt days of the Empire. What

higher or more dignified sense of duty could there be than that

exhibited by the lady who had determined to send substantial relief to

a friend of hers, banished by Domitian? It was represented to her that

this money would be certain to fall into the tyrant's hands, and that

hence she would be only wasting her means and gratifying the unworthy.

"It is of little consequence to me," she said, "if Domitian steal it;

but it is of great moment for me to send it." She possessed the sublime

conviction that she was responsible to her consciousness of what

friendship demanded, even though she might be certain of the miscarriage

of her efforts.

There were also women whose spirits were stirred by the love of freedom,

and who were willing to do and dare and suffer in the attempt to wrest

the nation from a tyrant's grasp. Among those who have sacrificed their

own lives at the altar of Liberty, the Roman woman can claim

representatives.

We are told that into the conspiracy against Nero which was headed by

Caius Piso, "senators, knights, soldiers, and even women entered with

the ardor of competition." The plot was to attack Nero while he was

singing upon the stage, though it was considered by some that it would

be a better plan to set his house on fire and then despatch him while he

was excitedly hurrying about unattended by his guards. "While the

conspirators were hesitating, and protracting the issue of their hopes

and fears, a woman named Epicharis--and how she became acquainted with

the affair is involved in mystery, nor had she ever manifested a concern

for worthy objects before--began to animate the conspirators, and goad

them on by reproaches; but at length, disgusted by their dilatoriness,

while sojourning in Campania, she tried every effort to shake the

allegiance of the officers of the fleet at Misenum, and engage them in

the plot."

But, though an enthusiastic conspirator, Epicharis proved herself an

unwary recruiting agent. She especially applied herself to an old

acquaintance named Proculus, who confided to her the fact that he had

been one of the party concerned in the assassination of the emperor's

mother, and that he was dissatisfied with the reward he had received for

such eminent service, he being only a minor officer in the fleet. He

added that it was his settled purpose to be revenged, should a fitting

opportunity present itself. Epicharis did not wait to consider the

unwisdom of incontinently intrusting the knowledge of the whole plot to

a man of insufficient principle to prevent him from looking upon the

murder of a defenceless woman as an exploit to be liberally rewarded.

Moreover, it is likely that she inadvertently had dropped some hint of

what was in her mind, and Proculus lured her on by suggesting the

possibility of himself as a convert. Epicharis first gave him the whole

plot, and then set about persuading him to join it. She recounted all

the atrocities of the emperor; and concluded with the remark "that Nero

had stripped the Senate of all its powers; but," she added, "measures

had been taken to punish him for overturning the constitution; and

Proculus had only to address himself manfully to the work and bring over

to their side the most energetic of the troops, and he might depend upon

receiving suitable rewards."

One indiscretion she did not commit: she did not divulge the names of

the conspirators. So, when Proculus laid information before the

emperor--thinking doubtless that this was a readier path to reward than

any plot of assassination of which a woman would be cognizant--his

evidence was of little avail; but Nero considered it best to detain

Epicharis in prison, in anticipation of anything that might occur.

The conspirators at last concluded to perpetrate their design at the

Cirensian games. Lateranus, a man of determined spirit and gigantic

strength, was to approach the emperor as a suppliant and, apparently by

accident, throw him down. Scævinus was to perform the principal part

with a dagger he had procured from the temple of Fortune for the

purpose. Piso was to wait at the temple of Ceres until he was summoned

to the camp, which he was to enter attended by Antonia, the daughter of

Claudius Cæsar,--a woman of an entirely opposite character to that of

her grandmother, after whom she was named,--and who, it was hoped, would

conciliate the favor of the people. How deeply Antonia was involved in

this plot it is impossible to say. It appears improbable, as Tacitus

remarks, that she should have lent her name and hazarded her life in a

project from which she had nothing to hope.

It was through the dagger mentioned above, and also the cupidity of a

woman, that the whole conspiracy came to light. Scævinus impatiently

ordered his freedman Milichus to put the weapon to the grindstone and

bring it to a sharp point. Milichus, putting together this and other

preparations he witnessed, guessed the project that was on foot. He told

his suspicions to the emperor. Scævinus was arrested; but his bearing

was so confident that the accuser would have broken down had not the

wife of Milichus reminded him that "Natalis had taken part in many

secret conversations with Scævinus, and that both were confidants of

Piso." Then followed numerous arrests, confessions, and accusations,

each conspirator endeavoring to lighten the burden of his own guilt by

revealing how many there were who shared it. Lucan the poet even

informed against his own mother, Atilla.

Amid all this disaster, there was one spirit that remained undaunted,

one tongue that could not be persuaded by promises or compelled by

torment to confess and thus implicate others. Epicharis had been held

in custody from the time of her unguarded enthusiasm in Campania. Nero

recollected her, and commanded that she should be put to the torture.

"But," says the historian, "neither stripes, nor fire, nor the rage of

the tormentors, who tore her with the more vehemence, lest they should

be scorned by a woman, could vanquish her." Thus the first day of

torture was passed without producing any effect upon her. "The day

following, as she was being brought back to suffer the same torments,

riding in a chair, for all her members being disjointed, she could not

support herself, taking off the girdle that bound her breast, she tied

it in a noose to the canopy of the chair, and, placing her neck in it,

hung upon it with the weight of her whole body, and thus forced out the

slender remains of life. A freedwoman, by thus screening strangers and

persons almost unknown to her, though pressed to divulge their names by

the most extreme torture, exhibited an example which derived augmented

lustre from the fact that freeborn persons, men, Roman knights, and

Senators, untouched by the instruments of inquisition, all betrayed

their dearest pledges of affection."

Among the many who suffered from the discovery of this conspiracy was

Seneca, the aged philosopher and the former tutor of Nero. It is

probable that he was innocent; but he had incurred Nero's displeasure,

and the tyrant was glad of the opportunity to destroy him with seeming

justice. The parting of Seneca with his wife and her conduct at the time

well merit the pains which the historian has taken with the recital.

Embracing his wife, he implored her to "refrain from surrendering

herself to endless grief; but to endeavor to mitigate her regret for her

husband by means of those honorable consolations which she would

experience in the contemplation of his virtuous life." Paullina,

however, expressed her determination to die with her husband, and called

for the assistance of the executioner to open her veins. Seneca, proud

of her devotion and as willing to see her acquire the glory of such an

act as he was to be assured that she was safe from the hard usages of

the world, replied: "I had pointed out to you how to soften the ills of

life; but you prefer the renown of dying. I will not envy you the honor

of the example. Though both display the same unflinching fortitude in

encountering death, still the glory of your exit will be superior to

mine." Then they had the veins of their arms opened at the same moment;

but being unable to bear up under the excessive torture, and afraid lest

the sight of his sufferings should overpower her, Seneca persuaded his

wife to retire into another room.

When Nero heard what was being done, having no dislike to Paullina, and

not willing to incur the odium of a double death and one so affecting,

he ordered her wounds to be dressed and the flow of blood stanched. She

survived but a few years, and these were devoted to the memory of her

husband. It is also said that an excessive paleness was the continuous

witness to the sacrifice to conjugal devotion which she had done her

best to make.

Not so fortunate was Servilia, a young woman of twenty who, at this

time, was arraigned before the Senate, charged with having distributed

sums of money among the magi. Servilia was the daughter of Soranus, who

had been Proconsul of Asia. There was no accusation against Servilia's

father more severe than that he was a friend of Plautus, whom Nero, for

reasons utterly unjust, but entirely satisfactory to himself, had caused

to be executed. Tacitus suggests the picture of her trial: the consuls

on the judgment seat in the presence of the assembled Senate; on one

side of that tribunal, an old, gray-haired man who for many years has

served his country with honor and integrity; on the other side, the

daughter, so young and yet widowed, for her husband has been sent into

banishment, and hence is as dead to her. The thought that she, who had

endeavored to aid and comfort her father, had only added to his dangers

is so oppressive that she has not the heart to look at him. The accuser

questions her: "Did you not sell your bridal ornaments, and even the

chain off your neck, to raise money for the performance of magic rites?"

Instead of answering, the unfortunate girl falls to the floor, embracing

the altar, as though hoping that divine aid would be given, where human

mercy was not to be expected. At last she gathers voice, and is able to

falter: "I have used no spells; nor did I seek aught by my unhappy

prayers than that you, Cæsar, and you, fathers, would preserve this best

of fathers unharmed. It was with this object alone I gave up my jewels,

my raiment, and the ornaments belonging to my station; as I would have

given up my blood and life, had the magi required them. To those men,

till then unknown to me, it belongs to declare whose ministers they are,

and what mysteries they use; the prince's name was never uttered by me,

save as one speaks of the gods. Yet to all this proceeding of mine, if

guilty it be, my most unhappy father is a stranger; and if it is a

crime, I alone am the criminal." Then Soranus pleads for his daughter.

Her age is so tender that she could not have known Plautus, whose friend

they accuse himself of being. Do they impeach him for mismanagement of

his province? Let it be so; yet his daughter had not accompanied him to

Asia. Her only crime was too much filial piety, too great solicitude for

her father. He would gladly submit to whatever fate awaited him, if only

they would separate her case from his. Overcome with emotion, the old

man totters forward with outstretched hands to embrace his daughter,

who springs to meet him; but the stern lictors interpose the fasces and

deny them this sad comfort.

The Senate exercises a heartless clemency; Servilia and Soranus are

allowed to choose their own deaths. This faithful daughter, for seeking

by means of her religion to aid her father, is privileged to die with

him. With them also perished Thrasea, who had added to his crime of

disbelieving in the deification of Poppæa that of neglecting to

sacrifice for the preservation of Nero's beautiful voice!

A strikingly magnificent feature of the old Roman character is the

manner in which these people met death. This was the one virtue which

the Romans, down to the latest period of the decadence, did not cease to

retain. In the most dissolute times, the Roman might live badly, but at

least he could die bravely. This was the one opportunity always left

when atonement might be made for the errors of life. In this ability to

meet death with calm fortitude the women shared no less than the men.

The maids and matrons of Rome were habituated by training and by their

best traditional examples to look upon the possibility of exit from the

world as an ever ready refuge from unendurable ills. Lucretia was for

Roman matrons an ideal in her death as well as in her life; and they

seem to have found it less irksome to follow her in the former respect

than in the latter.

In the endeavor to show how, even in the days of Nero, when wickedness

reached its climax, virtue and honor and devotion were not utterly gone

out of the world, it has been necessary to adopt as illustrations some

of the saddest of the many tragedies of human history. Neither side of

any true picture of this period can be a pleasing one. Human life in the

city of Rome during the middle of the first century of our era was for

the most part either insane or sad. To exult in unrighteousness or

mourn in bereavement was the lot of every prominent personage; for there

were few quiet, honorable folk whom the hand of tyranny did not touch

through their friends. Therefore, in the endeavor to show the better

side of the life of this time, the necessity has been forced upon us to

illustrate how the prevailing remnant of the ancient virtue was

manifested in the devotion of women to their stricken husbands and

friends, and in the firm manner in which they met their own death.

That which belongs to the ordinary routine of woman's life did not

undergo any change during this period. The status of woman remained

unaltered; her manners, customs, and occupations were the same. There

was no progress. It was like the conditions existing in a home during a

terrific electrical storm; all other interests are in abeyance until it

is over.

This statement, however, applies more particularly to the city of Rome

and to Italy. In the outlying parts of that country and in the

provinces, the storm was hardly felt. Women who lived out of the sight

of Nero and whose male friends did not hold office were secure from

imperial cruelty and caprice. Their lives ran on in the ordinary manner

of civilization. They were betrothed and married according to the

ancient ceremonies; for customs changed slowly away from the metropolis.

They worshipped the old gods, though they heard now and again of a

certain sect of fanatical people who courted their own destruction from

the officials, if not from Olympus, by denouncing the ancient worship.

They managed their homes and their slaves, read their books, as we have

seen in the case of Calpurnia, the wife of Pliny, and visited the

amphitheatre. The only anxieties of the women who belonged to the

unofficial class were those incidental to the rule of the proconsuls who

were sent to govern them in the name of the emperor. Sometimes these

men were lustful; frequently they were tyrannical; they were always

rapacious. The people were oppressed to meet the demands of the tax

collectors; but these were ills that were always with them and

represented a condition of affairs that was normal.

In his biography of his father-in-law, Agricola, who was himself a

provincial, Tacitus says: "He married Domitia Decidiana, a lady of

illustrious descent, from which connection he derived credit and support

in his pursuit of greater things. They lived together in admirable

harmony and mutual affection, each giving the preference to the other;

a conduct equally laudable in both, except that a greater degree of

praise is due to a good wife, in proportion as a bad one deserves the

greater censure." What more touching expression of family affection can

there be found than the words Tacitus wrote in respect to Agricola's

death? Apostrophizing him, he says: "But to myself and your daughter,

besides the affliction of losing a parent, the aggravating affliction

remains that it was not our lot to watch over your sickbed. With what

attention should we have received your last instructions, and graven

them on our hearts! This is our sorrow. Everything, doubtless, O best of

parents, was administered for your comfort and honor, while a most

affectionate wife sat beside you; yet fewer tears were shed upon your

bier, and in the last light which your eyes beheld, something was

wanting." There is nothing in modern times superior to this in chaste

and cultivated sympathy.

Seneca also, who was born at Cordova, describes his mother as having

been "brought up in a strict home"; and he assures us that his aunt,

during the sixteen years that her husband governed Egypt, was "unknown

in the province," so devoted was she to her family and home duties.

There was also Polla, the wife of Lucan, whose inconsolable grief at her

husband's death was so beautifully described by Statius. We read also of

Minicius Macrinus, who lived thirty-nine years with his consort without

a single cloud ever rising between them; while Martial tells us of

Spurinna, a man of consular family loaded with years and honors, who

lived in the country with his aged wife, each resting in the other's

affection, and finishing together "the evening of a fair life."

UNDER THE FLAVIANS

Such sober-minded people as had survived the reign of Nero hailed the

tyrant's death as a deliverance, though they had no guaranty of the

inauguration of a better state of things. No conceivable change could be

otherwise than for the better. At first sight, it seems marvellous that

the better class of Romans endured so long and with such supineness a

shameful monstrosity like the government of Nero; but it must be

remembered that no government is other than the majority of the people

desire, or better than they deserve. The mass of the people in the

capital were satisfied to have an imperial mountebank ruling over them.

Politics had ceased to interest them, they having wholly forfeited their

liberties. They cared naught for the fortunes of the Empire, so long as

the wheat ships came regularly from Alexandria. The only vestige of

independence they retained was the privilege of shouting with impatience

when the games were delayed; there were no further rights they cared to

demand when Nero, dining in his box at the amphitheatre, threw his

napkin from behind the curtains as a signal that he had finished and

that the sport might commence. With such a populace as this, the nobler

spirits in the city could hope to accomplish nothing. Their only

recourse was to glorify their passive sufferings and their death with

stoical calmness and undismayed pride. How hopeless it was to expect the

inauguration of a revolt among the common people of Rome is shown by the

attitude of these people toward Nero's memory after his death. For a

long time, his tomb was continually decked with flowers. Sometimes, his

admirers placed his image upon the rostra, dressed in robes of state;

again, they would publish proclamations in his name, as though he were

yet alive and would shortly return and avenge himself upon his enemies.

Occasionally, there were rumors of his reappearance, for the reality of

his death was doubted in many quarters, and the undisguised satisfaction

with which these reports were received is evidence that the Roman people

generally were not yearning for reform.

But those who were absent in the provinces, being neither under the

immediate power of Nero nor partners in his excesses, did not endure

with such complacence the shame he put upon the Roman name. Men like

Galba and Vespasian heard with great indignation from scoffing

foreigners how, at Rome, they had seen the emperor acting Orestes or

even Canace on the stage. These men could not endure the thought of

serving under a ruler who competed with a slaveborn pantomimist. Revolt

flamed up among the legions in various parts of the Empire; the guards

at Rome joined in it; and when Galba came, who had been proclaimed

emperor, they gladly welcomed him.

Rome was shaken in the very foundations of her constitutional ideals.

The discovery of the possibility that an emperor could be created away

from the city marked the entering of the wedge which was eventually to

bring about the disintegration of the Empire. The legions had come

clearly to realize that the gift of the Empire was in their hands. The

Senate was henceforth supernumerary. The city was no longer to be

viewed with that superstitious reverence which had made men deem nothing

sacred or authoritative that had not issued therefrom; it was the

centre, but no longer the source of Empire. It soon came to pass that

"Roman" signified wide-spreading national inclusion rather than, as

heretofore, racial exclusion; even a Jew might now claim to be a freeborn

Roman citizen, though he had never seen the Capitol.

In consequence of opposing claims to the succession, Italy was once more

torn with civil strife, an experience from which she had been free ever

since the days of the last Triumvirate. Within eighteen months three

emperors were created and destroyed.

Our story, however, does not deal with emperors or with the political

history of Rome, except as it is necessary to refer to it as a

background for, or an explanation of, the conduct of the women who are

herein introduced. Women played no important part in the disturbances

which shook the Empire after the death of Nero, and which thus differed

from many of the previous revolutions in the State; yet it is entirely

consistent with the plan of this work to mention the women who were

connected with the principal actors.

Galba, who was an old man when he came to the throne, had been in his

youth a great favorite of the Empress Livia. By her he had been advanced

in fortune and position. His mother's name was Mummia Achaica, the

daughter of Catulus; but she probably died when he was very young, and

he owed the benefits of his training to Ocellina, his stepmother, who

was a very remarkable woman in more than one respect. Beautiful and very

wealthy, she herself made the advances in courtship to Galba's father.

The elder Galba became consul and was of considerable importance in the

State; but he was a very short man and deformed. There is an

interesting story to the effect that once, when Ocellina was pressing

her suit, Galba, in order that if there were to be any disillusionment

on her part in regard to himself it might take place before he gave her

his hand, took off in her presence the toga which hid the deformity of

his back. The incident shows a praiseworthy ingenuousness of disposition

on the part of Galba; it also indicates, what is of more interest to us,

the fact that Roman ladies were not unaccustomed to making matrimonial

advances in person and with unmistakable directness of purpose. Galba,

the future emperor, was adopted by Ocellina as her own son; and it is

safe to assume that the honesty of his character was in a large degree

the result of her training as well as an inheritance from his father.

Galba was married to Æmilia Lepida, a descendant of the triumvir; but

she died during the reign of Claudius, and he never afterward married,

even though he was ardently sought by Agrippina the Younger, who had

been cuffed by his mother-in-law for seeking to usurp the place of

Lepida while the latter still lived.

During the short eight months of his reign, Galba was almost entirely

ruled by the influence of Titus Vinius and Piso Licinianus, both of whom

perished with him, the latter having been designated by him as his

successor. Vinius met a fate which he richly deserved, and which,

unfortunately for many Romans, he escaped, though barely, in the days of

Caligula. At that time, he disgraced himself as the accomplice and

paramour of Cornelia, the wife of his commander, Sabinus, she who

paraded the camp at night in the dress of a common soldier. Cornelia,

however, expiated her crime by her devotion to her husband in his

misfortune at a later day. Vinius attained to fortune by means of

methods which are well illustrated by the indignity to which he

submitted his daughter Crispina at the hands of the depraved Tigellinus.

During Galba's reign, the people, believing Nero to have been incited to

his worst acts by Tigellinus, demanded the latter's execution, Vinius

preserved him from their rage, and thereupon Tigellinus gave a splendid

banquet as a thanksgiving for his deliverance. This entertainment

Crispina attended, accompanied by her father, who allowed her to receive

from their host an immense sum of money. Tigellinus on the same occasion

commanded his chief concubine to take from her own neck an extremely

valuable necklace and place it upon that of Crispina. But she was soon

compelled to expend her ill-gotten gains in a most pitiable manner.

After the death of Galba, Piso, and Vinius, the soldiers amused

themselves by carrying their heads about the city on the points of

spears. When Crispina and Verania, the wife of Piso, visited the camp

for the purpose of imploring the heads of their relatives, in order that

they might be disposed of with funereal honor, Crispina was not allowed

to take that of her father until she had purchased it at a cost of

twenty-five thousand drachmas.

Otho, who had been the husband of Poppæa Sabina, was the next emperor;

but his reign lasted less than four months, and his only praiseworthy

act is the noble manner in which he died. Then came the brief and

shameful reign of Vitellius. Rome needed only to come under the rule of

a glutton to have exhibited by turn upon her throne a monstrous example

of every form of vice to which human nature can become addicted.

This man was the son of that Vitellius who had so shamelessly flattered

Messalina and so basely deserted her in her extremity of need. His

mother's name was Sextilia, and she is reported to have been a most

excellent and respectable woman, whose character was formed on the

model of the ancient morals. Her death is said to have been brought

about by her son, in order that the prediction of a German prophetess

might be certain of fulfilment, she having told him that, he would reign

in security, if he survived his mother. He is accused of having denied

her proper nourishment during her illness. Suetonius, however, adds,

"that being quite weary of the woeful state of affairs, and apprehensive

of the future, she obtained without difficulty a dose of poison from her

son."

Petronia was the first wife of Vitellius. A separation took place which

was probably mutually agreed upon, for Petronia bequeathed her property

to their son; first requiring, however, that he be released from his

father's authority, Vitellius agreed to this; but shortly after, the son

died by poison believed to have been administered by his father. A woman

named Galeria Fundano became the second wife of Vitellius; but of her

nothing more is known than that Tacitus speaks of her gentle

disposition.

With Vitellius, to reign meant merely to feast royally. In this,

however, he was only the leading and most noteworthy exponent of a vice

characteristic of his time. Gluttony, among the Romans, had come to be

exalted to an art; and, in proof that the women of those days were not

exempt from it, historians inform us that it was common for individuals

of the female sex to be afflicted with the gout. Suetonius thus

describes the kind of feasting to which Vitellius accustomed the

nobility of Rome: "At a supper given him by his brother, on the day of

his arrival in Rome, there were served two thousand rare fishes and

seven thousand birds. But Vitellius threw into the shade all this

profusion by using on his own table a huge dish, which he named the

Shield of Minerva. In it were livers of plaice, brains of pheasants and

peacocks, flamingoes' tongues, roe of lamprey, and a thousand other

things which the ships of war had sought from the remotest border of

the Euxine to the Pillars of Hercules."

This dish of Vitellius was made of silver. What its exact weight was we

do not know; but inasmuch as a freedman of Claudius had constructed one

of five hundred pounds weight, which was evidently inferior, we can well

believe the ancient writer when he tells us that the Shield of Minerva

was of such prodigious size that a special furnace had to be constructed

for its manufacture. It was kept as a monument of extravagance until the

time of Hadrian, who caused it to be melted.

The brief reign of Vitellius was closed in a paroxysm of civil strife,

which ended within the walls of the city itself. For more than a hundred

years,--ever since the sack of Perusia, in which Fulvia played so

prominent a part,--the women of Italy had been free from the bitter

experiences of war. They knew nothing of the cruelties and atrocities

which followed in the wake of ancient battle, except from stories told

by grandmothers at nightfall. Now they were to suffer those evils

themselves.

In warfare, more than in any other experience, man reverts to his

original barbarous, or rather purely animal, type. It is noticeable also

that in war, and especially in civil war, women regain some of that

ferocity which characterizes the female of the lower types of animals.

In the reign of terror during the French Revolution, there were many

women who showed themselves as bloodthirsty as any of the men who

composed the Committee of Public Safety. So, in the struggles which

accompanied the short-lived reigns of these three Roman emperors there

were many women who engaged in the battles; and there were some who

distinguished themselves by conduct not often exhibited to the discredit

of the female sex. Triaria, for example, who was the wife of Lucius

Vitellius, the brother of the emperor, is described as having been a

woman of the most furious spirit. When Dolabella, who had married

Petronia, was in danger of his life, Triaria warned a friend who sought

to save him that it would not be good for that friend to seek the

exercise of clemency; and when Tarracina was sacked by the Vitellian

soldiers, this same Triaria, armed with the sword of a soldier, urged on

the men to murder and rapine.

In the final strife between the forces of Vitellius and Vespasian, the

city of Cremona, which was held by the former, was besieged. Tacitus

informs us that, in their zeal for the cause which their city had

adopted, some of the women of Cremona took part on the field of battle

and were slain. In view of what followed at the taking of their city,

they were fortunate in their lot. "Forty thousand men," says the

historian, "poured into it. The number of drudges and camp followers was

still larger, and more addicted to lust and cruelty. Neither age nor

dignity served as a protection; deeds of lust were perpetrated amidst

scenes of carnage, and murder was added to rape. Aged women who had

passed their prime, and who were useless as booty, were made the objects

of brutal sport. Maidens were contended for by ruffians who ended by

turning their swords against each other."

The bloodshed and rapine were carried into the city of Rome itself. When

he saw that his case was hopeless, the ignoble, indolent Vitellius

wished to abdicate; but this neither his soldiers nor the people would

allow him to do. Flavius Sabinus was prefect of the city, and he, with

the soldiers of the Vespasian party, took refuge in the Capitol. There

were women who voluntarily took their places with these besieged men.

Among them was Verulana Gratilla, who, having neither children nor

relatives, followed the fortunes of the war for no other apparent reason

than the pleasure she derived from scenes of carnage. In this conflict

the Capitol was fired and the temple of the Empire reduced to ashes.

Yet, while all these things were occurring, the common people of Rome,

indifferent as to whether they were ruled by Vitellius or Vespasian,

looked on as if they were at a gladiatorial show. It was to them nothing

more than a spectacle, except that it was also an occasion for absolute

lawlessness and an incitement to frenzied indulgence in everything

vicious. So brutalized were the people that, while in some parts of the

great city the streets were filled with heaps of slain, in other parts,

to which the conflict did not extend, there prevailed revelry of the

most frantic kind, in which shameless women took a leading part.

The legions of Vespasian conquered; and with his enthronement Rome

returned to peace and sanity. The enormities in which she had indulged

since the reign of Augustus were for the time expiated.

In the Flavians, a new and healthy dynasty came to the throne of the

Cæsars, though not later than the third reign, that of Domitian, it also

was to succumb to the effects of the possession of unbounded power.

Vespasian had come from an obscure family living at Reate in the Sabine

country. His father had collected the revenue in the province of Asia,

where his statue had been erected with the inscription: The Honest Tax

Collector. His mother, whose name was Vespasia Polla, was descended

from a good Umbrian family. Tertulla, his grandmother by his father's

side, had charge of his education, and her memory was always held by him

in the highest regard; much more than appears is suggested in the remark

of Suetonius that, after his advancement to the Empire, Vespasian loved

to visit the place where he spent his childhood. The house and all the

surroundings were kept exactly in the same condition, so that amid

unchanged scenes he might live over again his boyhood days. It was a

simple country house, with no pretension to the splendor in which the

great mansions of the city vied with each other; yet it was artistic.

In those times, not even the simplest farmstead was without its

statuary; and we may well believe that, as Tertulla, in the courts of

Phalacrine, superintended the education of the future builder of the

Colosseum, she could point to examples of sculptured beauty to

illustrate those ideas of art which were included in every Roman's

training. In the great common room, where the work of the house was

done, and where, on winter evenings, the slaves were kept busy with

useful occupations, Polla presided, as had the matrons of the old days.

In the atrium she entertained her rural neighbors in simple style; and

there also she sometimes lectured her son, who greatly displeased her by

his tardiness in putting off his boyish ways. She was ambitious for him,

and longed to hurry him away to Rome, that in the stir of the city or

the camp he might win renown for the Vespasian name. Polla little

understood that the time her son spent, idly, as she supposed, watching

the teams and cattle about the drinking troughs of the inner court, was

fortifying him to withstand the moral dangers of a court of another

sort. The rugged, straightforward, simple-mannered soldier, who honored

festival occasions by drinking from a silver cup which he treasured as a

keepsake from his grandmother, was such an emperor as the Romans had not

before seen the like of.

Flavia Domitilla was the wife of Vespasian; but she did not survive to

participate with him in the imperial dignity. Of her life and character

we know little. There is in existence but one likeness of her--a

colossal head found near Puteoli and now preserved in the Campana

Museum. This gives her the appearance of a strikingly handsome woman,

with a suggestion of pride, but not too powerful to overcome the aspect

of good nature. Suetonius says that she was at first the mistress of

Statilius Capella, a Roman knight. It may seem strange that a man of

Vespasian's character should marry a woman who had sustained such a

former relation; but in those times, wives with a past history in which

their present husbands had played no part were not so rare that they

were even remarkable. Domitilla enjoyed by birth all the legal

privileges of a Latin woman, but she was not a citizen of Rome until a

suit had been brought by her father for her in the courts. Possibly this

suit was instituted in regard to her inheritance of property; for the

privileges of citizenship, as they related to women, consisted of the

ability to receive legacies and bequeath property, and to form such

matrimonial unions as would be held valid when brought into question in

matters concerning property. It is very likely that the explanation of

the fact that Domitilla is spoken of as the mistress rather than the

wife of Statilius is to be found in the further fact that, he being a

Roman knight and she not yet a citizen of Rome, legal marriage could not

take place between the two. Suetonius tells us that after the death of

Domitilla, Vespasian renewed his union with his former concubine Cænis,

the freedwoman and former amanuensis of Antonia, whom he treated, even

after he became emperor, almost as if she had been his legal wife; and

it is safe for us to suppose that, had he been legally able to do so,

Vespasian would have made Cænis Empress of Rome.

Domitilla bore her husband three children: Titus and Doraitian, who

became emperors in succession, and Domitilla, who died before her father

attained to the purple.

The salutary influence of Vespasian's character was soon made apparent

in the improvement of Roman morals. He was not an energetic reformer;

but he curtailed those abuses which were most flagrant, and himself set

an example which those who desired his favor found it to their advantage

to follow. He expelled from the Senate those who were extraordinarily

vicious in their lives, and among them one who had, by request of Nero,

contended with a Greek girl in the arena. He required the Senate to pass

a decree that any woman who entered into a liaison with the slave of

another person should be herself considered a slave--a law which

indicates to what lengths the license of women had carried them during

the preceding reigns.

One act of cruelty to a woman stains the records of this reign. An

insurrection had been stamped out in Belgium; but Sabinus, the leader,

had made his escape. His house was burned; still he could easily have

escaped into Germany, but that he was unwilling to leave his young wife,

Eponia, unprotected as well as homeless. "He concealed himself in an

underground hiding place, whose entrance was known only to two faithful

freedmen. He was believed to be dead; and his wife, sharing the opinion

of those around her, had been for three days plunged in inconsolable

affliction. Being secretly informed, however, that Sabinus was alive,

she concealed her delight, and was conducted to his place of refuge,

where in the end she determined also to remain. After seven months, the

husband and wife ventured to emerge, and made a journey to Rome for the

purpose of soliciting pardon. But being warned in season that the

petition would be in vain, they left Rome without seeing the emperor,

and again sheltered themselves in their subterranean refuge. Here they

lived together during nine years. Being at last discovered, Sabinus was

taken to Rome, where Vespasian ordered his execution. Eponia had

followed her husband, and she threw herself at the emperor's feet.

'Cæsar,' she cried, showing her two sons, who were with her, 'these have

I brought forth and nourished in the tombs, that two more suppliants

might implore thy clemency.' Those present were moved to tears, and even

Vespasian himself was affected; but he remained inflexible. Eponia then

asked to die with him whom she had been unable to save. 'I have been

more happy with him,' she said, 'in darkness and under ground, than thou

in supreme power,' Her second request was granted her. Plutarch met at

Delphi one of their children, who related to him this sad and touching

story." Why this usually tolerant and always sensible emperor should

have been so inexorable on this occasion is a mystery.

There is another instance recorded, in which a woman of different

character, presenting a petition of another kind, received an

acquiescent response. A lady of rank pretending, as Suetonius puts it,

to be desperately enamored of Vespasian,--it must have been that she

hoped to achieve a permanent relationship with the widowed

emperor,--requested that which it would have been more consistent with

her modesty to have avoided. In addition to granting her petition,

Vespasian made her a present of four hundred thousand sesterces. When

his steward asked how he would have the sum entered in his accounts, he

replied: "For Vespasian's being seduced." Considering, however, the

parsimonious character which the historian attributes to this emperor,

we are more inclined to think that the sum must have been entered on the

credit side of the ledger.

Vespasian died in A.D. 79. The humor--which is the same thing as saying

the sanity--of the man is manifested in his remark, as he felt his life

ebbing away: "Well, I suppose I shall soon be a god." Pliny says of

him, "Greatness and majesty produced in him no other effect than to

render his power of doing good equal to his desire." Suetonius declares:

"By him the State was strengthened and adorned."

In this same year occurred the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

These two cities, by the manner in which they were by one event both

destroyed and preserved, have afforded us so much material for the study

of Roman home life that a reference to them is entirely in accord with

the plan of this book. Among the Romans, even more so than among

ourselves, woman's life was home life. As we look into those Pompeian

houses, which the catastrophe of a day rendered impregnable to the siege

of centuries, we see in reality before us much which the scraps of

information afforded by the ancient writers fail to make intelligible.

By a singular good fortune, we are in possession of the narrative

furnished by a trustworthy eyewitness of the disaster which overwhelmed

Pompeii; it is contained in the two letters which Pliny the Younger

wrote to Tacitus, informing him how Pliny and his mother watched the

eruption of Vesuvius while his uncle was perishing in the attempt to

rescue the wife of a friend and at the same time to satisfy his spirit

of inquiry. We will not recite the well-known account, except as it

refers to the women who, if for no other reason than that it was their

fate or fortune to be present on this memorable occasion, deserve a

mention in the history of Roman women. Pliny says: "On the twenty-fourth

of August, about one in the afternoon, my uncle was desired by my mother

to observe a cloud which appeared of a very unusual size and shape....

This extraordinary phenomenon excited his philosophical curiosity to

take a nearer view of it. He ordered a light vessel to be got ready, and

gave me the liberty, if I thought proper, to attend him. I preferred to

continue my studies.... As he was coming out of the house, he received a

note from Rectina, the wife of Bassus, who was in the utmost alarm at

the imminent danger which threatened her; for her villa being situated

at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, there was no way to escape but by sea;

she earnestly entreated him, therefore, to come to her assistance. He

accordingly changed his first design, and what he began with a

philosophical turn of mind he pursued with heroic purpose. He ordered

the galleys to put to sea and himself went on board, with an intention

of assisting not only Rectina, but several others, for villas stand

extremely thick upon that beautiful coast." In this design he was

unsuccessful; so he went to what is now called Castellamare, in the Gulf

of Naples. While there he was suffocated by the poisonous gases which

accompanied the eruption. In a second letter, Pliny describes his mother

and himself seeking to escape from the effects of a "black and dreadful

cloud, bursting with an igneous, serpentine vapor, darting out a long

train of fire, resembling flashes of lightning, but much larger.... Soon

the cloud seemed to descend, and cover the whole ocean, as indeed it

entirely hid the island of Caprese and the promontory of Misenum. My

mother strongly conjured me to make my escape, at any rate, which, as I

was young, I might easily do; as for herself, she said, her age and

corpulency rendered all attempts of that sort impossible. However, she

would willingly meet death, if she could have the satisfaction of seeing

that she was not the occasion of mine. But I absolutely refused to leave