Silius was a noble, with a nobleman's privileges and also hislimitations. The class next in rank below his consisted of the"knights," of whom something has already been said. It will beremembered that these men of the "narrow stripe" were the highermiddle class, who conducted most of the greater financial enterprisesof Rome and the provinces. While the senatorial order could govern theimportant provinces, command legions, possess large estates, andderive revenues from them, but could make money in other ways onlythrough the more or less concealed agency of knights or their ownfreedmen, the knights were free to act as bankers, money-lenders,tax-farmers, and merchants or contractors in a large way, and to takecharge of such third-rate provinces as the Caesar might think fit toentrust to them. Money-lending at Rome was an extremely profitablebusiness. Not only was the nobleman often extravagant in his tastes,but when once elected to a public position he was practicallycompelled to spend money lavishly in giving shows and exhibitions ofthe kind which will be described immediately, or upon some publicbuilding, or otherwise. In consequence he often incurred heavy debts.Meanwhile the smaller traders and agriculturists, who were incompetition with slave-labour and other false economic conditions, tosay nothing of bad seasons, were frequently in the hands of theusurers. Though efforts were repeatedly made to check exorbitant ratesof interest, they were apparently quite as ineffectual as with us. Analmost standard charge was at the rate of one-twelfth of the loan, or8-1/3 per cent, but another common rate was that of one per cent permonth. Rates both higher and lower are known to us from particularcases. Naturally the question depended on the security, when it didnot depend upon the greed of the one side and the ignorance of theother. Much, however, of what the books call money-lending was onlywhat we should consider legitimate banking. Be this as it may, theknights made large fortunes from the practice. They were also thetax-farmers, who operated in the case of those imposts which werestill left indirect. The practice was to make an estimate of theamount of such a tax derivable from a province, to purchase it fromthe government at as large a margin of profit as possible, and sorelieve the state of the trouble and cost of collecting it. For thispurpose "companies" were formed, with what we should call a "legalmanager" at Rome. The managers would bid at auction for the tax, paythe purchase-money into the treasury, and proceed to get in the taxthrough local managers and agents in the provinces concerned. It hasalready been explained that the more important taxation of the empirewas at this date direct--a community in Gaul, Spain, Asia Minor, orSyria knowing what its assessment was, taking its own measures, andusing its own native or local collectors. The knights at Rome mightstill advance sums to such communities, but they were not in this casetax-farmers. It is unfortunate that the word "publicans"--bracketedwith "sinners"--is used in the New Testament translation for the localcollectors like St. Matthew. Not only does the word convey either nonotion or a wholly incongruous one to the ordinary reader, but it isapt to mislead those who know its origin. Because the financialcompanies at Rome, in purchasing the taxes, were taking up a publiccontract, they were called publicani. But it is not these men whowere themselves acting as petty collectors--in any case they hadnothing to do with the native collectors appointed by thecommunities--and it is not these who enjoyed an immediate associationwith "sinners." The fact is that the Latin word applied to the greattax-farming companies, who were acting for Rome, was afterwardstransferred to even the smallest collecting agent with opportunitiesfor extortion and harshness.

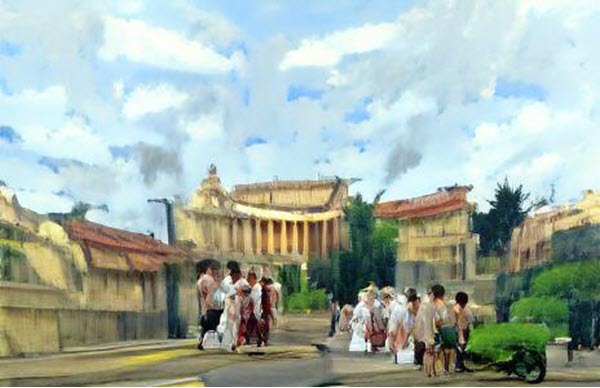

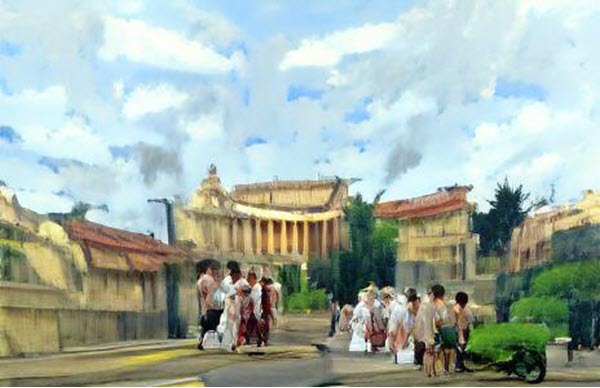

The stratum of Roman society below the knights was extremelycomposite. The slaves, of course, are not included. They have no rightto the Roman "toga," nor may they even wear the conical Roman cap,except at the Saturnalia, when everything is deliberately topsy-turvy.Omitting these, we may roughly divide the rest, as the Romansthemselves divided them, into "people" and "rabble." The rabble areeither persons without regular occupation, or lazzaroni, sheeridlers, loafers, and beggars. Doubtless many of them would execute anerrand or carry a parcel for a small copper, otherwise they would befound hanging about the public squares, lounging on the steps or inthe precincts of public buildings, such as temples, basilicas,porticoes, and baths, and playing at what the Italians call morra--amore clever and tricky species of "How many fingers do I hold up?"--orat "Heads or Tails." The poor of ancient Rome, like those of modernItaly, could subsist on very plain and simple food. Water, with a dashof wine when it could be got--and apparently at this date wine costless than a penny a quart--and porridge or bread, however coarse,would suffice, so long as there were amusements, sunshine, and no needto work. Every considerable city of the empire round the Mediterraneanwould doubtless contain its proportion of such "lewd fellows of thebaser sort," but it was naturally the imperial city that contained byfar the most. Rome was by no means the only city in which doles offree corn were made and free spectacular exhibitions given. But inother places the distributions were occasional and depended on thebounty of local men of wealth or ambition, whereas at Rome the dolewas regular, and the spectacles frequent and splendid. Rome was thecapital, and the abode of the emperor. It claimed the privileges ofthe Mistress City, including the enjoyment of the surplus revenues.Policy also demanded that the rabble should be kept quiet by "breadand games."

It is for these reasons that the names of some 200,000 citizens stoodupon a list to receive each month an allowance of corn--apparentlybetween six and seven bushels--at the expense of the imperialtreasury. This quantity they took away and made into bread as bestthey could. In many cases doubtless they sold it to the bakers andothers. It must be added that, apart from the free distribution, theimperial stores contained quantities of grain which could always bepurchased at a low rate. Occasionally a dole of money was added; inone case Nero gave over £2 per man. Meanwhile there was water inabundance to be had for nothing, brought by the carefully keptaqueducts into numerous fountains conveniently placed throughout thecity. While, however, we must recognise that the number of idlers wasvery large, we must be careful not to exaggerate. It is absurd toassume, as some have done, that because 200,000 citizens are receivingfree corn there are 200,000 unemployed. The Roman emperors neverintended to put a premium on laziness, but only to deal with poverty.In order to receive your dole of corn it was not necessary to showthat you were starving, but only that you were entitled, or in otherwords, on the list. It is also a mistake to think that any chancearrival among the Roman olla podrida could claim his bushel and ahalf of corn a week. In any case only Roman citizens couldparticipate. All the poorest workers, whether actually employed ornot, could take their corn with the rest. Nor must we forget thatamong the unemployed there were a considerable number who were, forone reason or another, only temporarily out of work. Nevertheless, itrequires no study of political economy to know, nor were Romanstatesmen blind to see, that the best way to make men cease to work isto show them that they can live, however shabbily, without. The reallysurprising thing is perhaps that the Roman government, with itsimmense funds and resources, stopped short where it did. An unsoundeconomic system had brought about difficult conditions, with which theemperors and their advisers dealt as best they could.

It was inevitable that among so numerous a pampered rabble, and somany impoverished aliens who tried their fortunes in the capital,there should be beggars in considerable numbers. We cannot tellprecisely how many they were. You might find them on the bridges,where they marked, as it were, a "stand" for themselves and crouchedon a mat, or at the gates, or wherever carriages must proceed slowlyon the highroads near the city, as for instance up the slope of theAppian Way as it passed over the south-western spur of the AlbanHills. Other towns would be infested in the same manner. Nor werethieves and footpads wanting in the streets or highwaymen upon theroads, especially in the lonelier parts near the marshes between Romeand the Bay of Naples. The city was, indeed, liberally policed, butRoman streets, as we have seen, were for the most part narrow,crooked, and unlighted at night. As usual, it was the comparativelypoor who suffered from the street robber; the rich, with their torchesand retinue, could always protect themselves.

After the "rabble" we will take the "people" in the sense current atthis date. We must begin by adjusting our notions somewhat. The Romansmade no such clear distinction as we do between trades andprofessions. To perform work for others and to receive pay for it isto be a hireling. Painters, sculptors, physicians, surgeons, andauctioneers are but more highly paid and more pleasantly engagedhirelings. Only so far do they differ from sign-painters, masons,undertakers, or criers. No doubt the theory broke down somewhat inpractice, yet such is the theory. That which in our day constitutes a"liberal" profession--a previous liberal education and a high code ofprofessional etiquette--can hardly be said to have existed in the caseof corresponding professions at Rome. If the liberality departs fromour own professional education and the etiquette is relaxed, we shallpresumably revert to the same state of things. A surgeon was commonlya "sawbones," and a physician a compounder and prescriber of more orless empirical drugs. Their knowledge and skill were by no meanscontemptible, and their instruments and pharmacopoeia weresurprisingly modern. Among the Greeks and Orientals their socialstanding was high, but at Rome, where they were chiefly foreigners,for the most part Greeks, the old aristocratic exclusiveness kept themin comparatively humble estimation, however large might be their feesin the more important cases. Something will be said later as to thestate of science and knowledge in the Roman world. For the present itis sufficient to note that artist, medical man, attorney,schoolmaster, and clerk belong theoretically to the common "people,"along with butchers, bakers, carpenters, and potters.

[Illustration: FIG. 69.--SURGICAL INSTRUMENTS. (Pompeii.)]

Setting aside the aristocratic and wealthy classes on the one hand,and the pauperised class on the other, we have lying between them theworkers, whether native Romans or the emancipated slaves, who are nowcitizens known as "freedmen." To these we must add the rather shabbygenteel persons whom we have already described as "clients." Amongworkers are found men and women of all the callings most familiar toourselves, with one exception. They do not include domestic servants.Romans who could afford regular servants kept slaves. It 18 true thatoccasionally one of the poorer citizens, even a soldier on furlough,might perform some menial task connected with a household, such ashewing wood or carrying burdens; but such services were regarded as"servile." With this exception there is scarcely an occupation inwhich Roman citizens did not engage. In such work they often had tocompete with slave-labour. It is probable, doubtless, that the greaterproportion of the slave body were employed as domestic servants. Butmany others tilled the lands of the larger proprietors. Otherslaboured under the contractors who constructed the public works.Others were used as assistants in shops and factories. It is obviousthat such competition reduced the field of free labour, when it didnot close it entirely, and the free labour must have been undulycheapened. But to suppose that all the Roman work, whether in town orcountry, was done by slaves is to be grossly in the wrong. Romans wereto be found acting as ploughmen and herdsmen, workers in vineyards,carpenters, masons, potters, shoemakers, tanners, bakers, butchers,fullers, metal-workers, glass-workers, clothiers, greengrocers,shopkeepers of all kinds. There were Roman porters, carters, andwharf-labourers, as well as Roman confectioners and sausage-sellers.To these private occupations must be added many positions in the lowerpublic or civil service. There was, for example, abundant call forattendants of the magistrates, criers, messengers, and clerks.Unfortunately our information concerning all this class is veryinadequate. The Roman writers--historians, philosophers, rhetoricians,and poets--have extremely little to say about the humble persons whoapparently did nothing to make history or thought. They are mentionedbut incidentally, and generally without interest, if not with somecontempt, except where a poet is choosing to glorify the simple lifeand therefore turns his gaze on the frugal peasantry, who doubtlessdid, in sober fact, retain most of the sturdy old Roman spirit. Aboutthe soldiers we know much, and not a little about the schoolmasters.The connection of the one occupation with history and of the otherwith authors will account for this fact. Something will be said of thearmy and also of the schools in their special places. Keepers of innsare not rarely in evidence in the literature of satire and epigram,and no language seems too contemptuous for their alleged dishonesty.But of inns enough has been said. We learn that the booksellersmade money out of the works of which they caused their slaves tomake copies, and which they sold in "well got up" style for fourshillings, or, in the case of slender volumes, for as little asfourpence-halfpenny. But to this day we do not know how much profit anauthor drew from the bookseller, or how it was determined, or whetherhe drew any at all. It is most reasonable to suppose that he sold abook straight out to the publisher for what he could get. Otherwise itis hard to see how any check could be kept upon the sales. The onlyoccupation upon which literature offers us systematic information isagriculture, including the pasturing of cattle and the culture of thevine. For the rest we derive more knowledge from the excavations ofPompeii than from any other source. From actual shops and theircontents, from pictures illustrating contemporary life, and frominscriptions and advertisements, we are enabled to reconstruct somepicture of commercial and industrial operations. We can see thefuller, the baker, the goldsmith, the wine-seller, and thewreath-maker at their work. We can discern something of the retailtrade in the Forum; or we can see the auctioneer making up hisaccounts.

[Illustration: FIG. 70.--BAKER'S MILLS. (Pompeii.)]

[Illustration: FIG. 71.--CUPIDS AS GOLDSMITHS. (Wall Painting.)]

[Illustration: FIG. 72.--GARLAND-MAKERS.]

[Illustration: FIG. 73.--BUST OF CAECILIUS JUCUNDUS.]

The baker, for example, was his own miller. There are still standingthe mills, with the upper stone--a hollow cylinder with a pinchedwaist--capable of revolving upon the under stone and letting the flourdrop into the rim below. Into the holes in the middle of the upper or"donkey" stone, and across the top, were fixed wooden bars, which wereeither pushed by men or drawn by asses yoked to them. The oven isstill in place, and, charred as they are, we are quite familiar withthe round flat loaves shaped and divided like a large "cross" bun. Thedough was kneaded by a vertical shaft with arms revolving in areceptacle, from the sides of which other arms projected inwards, sothat there was little room for the dough to be squeezed between them.We have pictures of the fuller, to whom the woollen garments--thetogas and tunics, and the mantles of the women--were regularly sent tobe washed by treading in vats, to be beaten, stretched, and bleachedwith sulphur, and to have their naps raised with a comb or a bunch ofthorns. The goldsmith is depicted at his furnace or his anvil. Thegarland-makers are at work fastening the blossoms or petals on aribbon or a tough strip of lime-bark. Dealers in other goods areshowing the results of their labour to customers, who carefullyexamine them by eye, touch, and smell. The tablets containing thereceipts for sales and rents still exist as they were found in thehouse of the shrewd-looking Jucundus the auctioneer. They formallyacknowledge the receipt of such-and-such sums realised at an auction,"minus commission," although unfortunately they do not happen to tellus how much the commission was. We see the venders of wine filling thejars for customers from the large wine-skin in the waggon. Inconclusion to this subject it should be observed that all manner ofdescriptive signs were in use; and just as one may still see abarber's pole or a gilt boot in front of a shop, or a painted sign ata public-house, so one might see the representation of a goat at thedoor of a milk-vender, or of an eagle or elephant at the door of aninn.

[Illustration: FIG. 74.--PLOUGH. (Primitive and later forms.)]

Meanwhile out in the country we can perceive the farm, with its hedgesof quick-set, its stone walls, or its bank and ditch. The ratherprimitive plough--though not always so primitive as it was ageneration or so ago in Italy--is being drawn by oxen, while, for therest, there are in use nearly all the implements which were employedbefore the quite modern invention of machinery. It may be remarked atthis point that the rotation of crops was well understood andregularly practised. Then there are the pasturelands, on the plains inthe winter, but in summer on the hills, to which the herdsmen drivetheir cattle along certain drove-roads till they reach the unfenceddomains belonging to the state. There they form a camp of huts orwigwams under a "head man," and surround their charges with strongfierce dogs, whose business it is to protect them, not only fromthieves, but also from the wolves which were then common on theApennines--where, indeed, bears also were to be met. There was no wantof occupation in the country in the time of haymaking, of the vintage,or of olive-picking. Even the city unemployed could gather a bunch ofgrapes or pick an olive, just as they can with us, or just as theLondon hop-picker can take a holiday and earn a little money in Kent.In the vineyards, where the vines commonly trailed upon low elms andother trees, various vegetables grew between the rows, as they stilldo about Vesuvius; on the hills were olive-groves, which cost almostnothing to keep in order, and which supplied the "butter" and thelamp-oil of the Mediterranean world.

[Illustration: FIG. 75.--TOOLS ON TOMB.]

We need not waste much compassion upon the life of the Roman workingclass. It is true that there was then no doctrine of the "dignity oflabour," but that there was reasonable pride taken in a tradereputably maintained is seen from the frequent appearance of its toolsupon a tombstone. In respect of the mere enjoyment of life, thelabourers, of the Roman world were, so far as we can gather, tolerablyhappy. They had abundant holidays, mostly of religious origin; but,like our own, so frequently added to, and so far diverted fromreligious thoughts, that they were more marked by jollity and sportthan by any solemnity of spirit. The workmen of a particular callingformed their guilds, "city companies," or clubs, in the interests oftheir trade and for mutual benefit. There was a guild of bakers, aguild of goldworkers, and a guild of anything and everything else.Each guild had its special deity--such as Vesta, the fire-goddess, forthe bakers, and Minerva, the goddess of wool-work, for thefullers--and it held an annual festival in honour of such patrons,marching through the streets with regalia and flag. Doubtless themembers of a guild acted in concert for the regulation of prices,although the Roman government took care that these clubs should benon-political, and would speedily suppress a strike if it seriouslyinterfered with the public convenience. The ostensible excuse for aguild, and apparently the only one theoretically accepted by theimperial government, was the excuse of a common worship. It is atleast certain that the emperors jealously watched the formation of anynew union, and that they would promptly abolish any which appeared tohave secret understandings and aims, or to act in contravention of thelaw. In the towns which possessed local government the municipalauthorities were still elected by the people; and the guilds,especially of shopkeepers, could and did play their parts indetermining the election of a candidate. The elections might make adifference to them in those ways in which modern town-councillors andmayors, may influence the rates, the conditions of the streets, therules of traffic, and so forth. There are sixteen hundred electionnotices painted, in red and black about the walls of Pompeii, and wefind So-and-So recommended by such-and-such a trade as being a "goodman," or "an honest young man," or a person who will "keep an eye onthe public purse." It is amusing to note that, in satirical parody ofsuch appeals as "the fruitsellers recommend So-and-So," we find that"the petty thieves recommend So-and-So," or we get the opinion of "thesleepers one and all." Special objects connected with these and otherassociations were the provision of "widows' funds," and of properburial for the members. Of the importance of the latter to the ancientworld we shall speak when we come to a funeral and the religious ideasconnected with it.

The most difficult task in dealing with antiquity is to visualise theactual life as it was lived. In the life of the humbler citizens theremains of Pompeii lend more help than anything else to the desiredsense of reality, but they are the remains of Pompeii, not of Rome.Nevertheless there are many points in which we may fairly argue fromthe little town to the larger, and it is customary to adopt thiscourse.

[Illustration: FIG. 76.--POMPEIAN COOK-SHOP.]

We may, therefore, think of the common people among these ancients asvery much alive in their frank curiosity, their broad humour, theirlove of shows, and their keen enthusiasm for the competitions, theirinterest in petty local elections, their advertising instincts, theirinsatiable fondness for scribbling on walls and pillars, whether inpaint or with a "style," a sort of small stiletto with which theycommonly wrote on tablets. The ancient world becomes very near when weread, side by side with the election notices, a line from Virgil orOvid scrawled in a moment of idleness, or a piece of abuse of aneighbouring and rival town--such as "bad luck to the Nucerians"--or apretty sentiment, such as "no one is a gentleman who has not been inlove," or an advertisement to the effect that there are "To let, fromJuly 1, shops with their upper floors, a flat for a gentleman, and ahouse: apply to Prinus, slave of So-and-So"; or "Found wandering, amare with packsaddle, apply, etc."--the latter, by the way, painted ona tomb.

[Illustration: FIG. 77.--IN A WINE-SHOP.]

For places of social resort there were the baths, the colonnades, thesemicircular public seats, the steps of public buildings, the shops,and the eating-houses and taverns. The middle classes, in the absenceof the modern clubs, met to gossip at the barber's, the bookseller's,or the doctor's. Those of a humbler grade would often betakethemselves to the establishments corresponding to the modern Italianosterie, where were to be obtained wine with hot or cold water andalso cooked food. As they sat on their stools in these "greasy andsmoky" haunts they might be compelled, says the satirist, to mix with"sailors, thieves, runaway slaves, and the executioner," but even menof higher standing were often not unwilling to seek low pleasures amidsuch surroundings, especially when, as was frequently the case, therewas provision for secret dicing beyond the observation of the police.

From literature, meanwhile, we may fill in their vivacious language,the courteous terms the people apply to each other, such as "you ass,pig, monkey, cuckoo, chump, blockhead, fungus," or, on the other side,"my honey, my heart, my dove, my life, my sparrowkin, my daintycheese." But to go more fully into matters like these would carry ustoo far afield.

We will end this topic with a last look at the ordinary free workman,who wears no toga, but simply a girt-up tunic, a pair of boots, and aconical cap, and who goes home to his plain fare of bread, porridge,lentil soup, goats'-milk cheese, "broad" and "French" beans, beetroot,leeks, salted or smoked bacon, sausages, and black-pudding, which hewill eat off earthenware or a wooden trencher, and wash down withcheap but not unwholesome wine mixed with water. He has no pipe tosmoke; he has never heard of tea, coffee, or spirits. He may have beentold that certain remote barbarians drink beer, and he may know of athing called butter, but he would not touch it so long as he can getolive-oil. However humble his home, he will endeavour to own a silversalt-cellar, and to keep it as an heirloom.