Prev

| Next

| Contents

THE WOMEN OF DECADENT ROME

At the period with which we are now engaged, the vast majority of the

people of Rome were giving their attention to one all-absorbing

occupation--that of amusing themselves. The wealthy had little else to

do; the chief industries of the poor contributed to this end. Never in

the history of the world has a nation been so completely given over to

pleasure. Production was almost entirely limited to such occupations as

had for their object the extravagant supply of the luxuries of art and

entertainment; common necessaries, such as wheat, were extorted from the

provinces. Agriculture had become almost unknown in Italy. The rich men

no longer, like the great republican patricians, prided themselves on

their skill in tilling the soil; it better suited their tastes, and was

more lucrative, to farm taxes. "We have abandoned the care of our ground

to the lowest of our slaves," said Columelia, "and they treat it like

barbarians. We have schools of rhetoricians, geometers, and musicians. I

have even seen where they teach the lowest trades, such as the art of

cooking, or of dressing the hair; but nowhere have I found for

agriculture a teacher or a pupil.

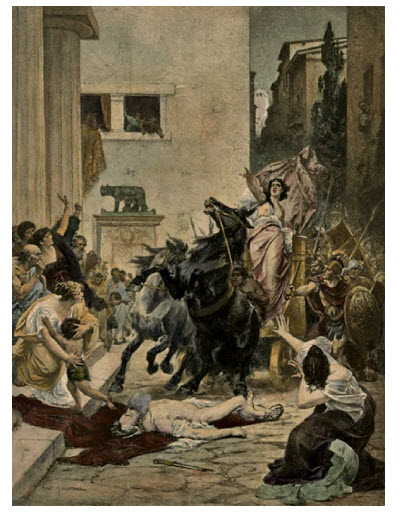

A Roman Banquet

A Roman Banquet

After the painting by Albert Baur

Around the tables, in place of chairs, are couches with an

abundance of soft pillow. These couches are placed on three sides of

the table; for it was the custom of the Romans to recline at their

meals. When this custom was first introduced from Asia, the

women did not think that it comported with their modesty to adopt

this new style, and until the end of the Republic they retained the

old habit of sitting at table.... After these entertainments have

been concluded, an enormous disk is set, and in it a great boar.

On his tusks, hang two baskets, one filled with dates, the other with

almonds. About him are little pigs made of sweetmeats; they are

presents to be carried away; it is the custom for men at a banquet

to carry some part of it to those women of their families who have

not been present..... when the servant makes a hole in the side

of this boar, as though to carve it, out fly a number of blackbirds,

which continue to flutter about the room until recaptured.]

Meanwhile, even in Latium, that we may

avoid famine, we must bring our corn from foreign countries and our

wine from the Cyclades, Boetica, and Gaul." The land had come to be held

almost wholly by the few who were exceedingly rich. Their interests were

in Rome. For the country they cared nothing, except as it provided them

with luxurious retreats where they might, for a short space, renew their

enervated faculties after the dissipations of the city. Their land they

gave up to pasture and cattle raising, as being more profitable and

requiring less care than tilling the soil. Thus there was no employment

or means of subsistence for poor freedmen in the country; and so they

flocked to the cities, crowding the wretched insulæ, or tenements, and

depending mainly upon the free distributions of corn for their living.

The mass of the people, however, were drawn to Rome and the other great

Italian cities as much by their desire to participate in the feverish

life of the times as they were driven thither by lack of employment in

the country. These were the people who amused Nero by fighting for

places in the Great Circus; these were the people who howled for bread

and for games, and rewarded an ample supply of the same by supporting

tyrants in their monstrous excesses. When it is remembered that all

domestic labor, as well as all work belonging to many other branches of

industry, was performed by slaves, we are necessarily left to suppose

that the proletariat of Rome had little with which to occupy itself

beyond the public exhibitions and the pothouses, of which there existed

an enormous number; great numbers of men were, however, required for the

immense armies which garrisoned the provinces.

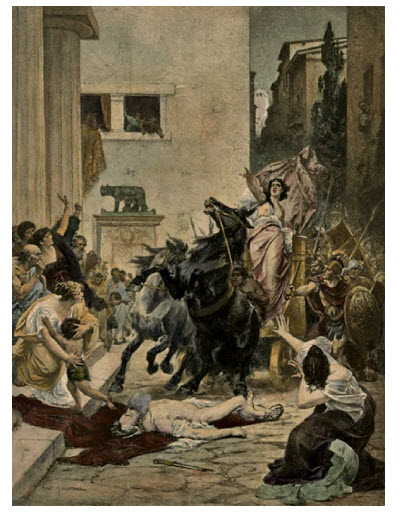

Tullia, Daughter of Servius

After the painting by E. Hildebrand

_We have had the good queen, now we encounter the

bad..... Tullia was of that type of which Shakespeare

has given a picture in Lady Macbeth.....

Lucius, her husband, with an armed band, repaired to the

Senate and seated himself on the throne. King Servius

appeared, but no one thought it worth while to hinder

Lucius from throwing the aged ruler down the steps of

the Senate house; which me manfully did.

Tullia was the instigator of this_ coup d'état; _and

impatient to learn its success, drove to the Forum, and,

calling her husband from the Senate chamber, was the

first to hail him as king. But Lucius commanded her

to return home; and the tradition runs that as she was

going thither her chariot wheels passed over the dead

body of her royal father._]

Of the domestic life of the common people of Rome we have only the most

meagre information. We know that they inhabited huge tenements, in which

small apartments were rented at excessive rates. Housekeeping in these

tenements must have been conducted on a very simple scale, as one of the

comic writers pictures a poor family moving to other quarters and

carrying all their effects in their hands at one journey. Yet the men

who issued thence wore the toga of the Roman citizen, tattered though

it might be and having no other significance than the mere fact that its

wearers were not slaves. For these men there was little occupation

except wandering about the city in search of amusement and the

opportunity to make a little gain by any means that came to hand. Of

course, there were trades and commerce, the workshop and the store; but

slavery made it impossible for a large proportion of the impecunious

citizens of Rome to make an honorable living by means of their own

labor. There was a larger army of the unemployed than our modern cities

can show. Yet the Roman government, laying tribute as it did upon the

whole civilized world, could keep the citizens of Rome from starving.

For the women, beyond their simple domestic duties, the field of honest

industry was yet more limited. They were employed as professional

mourners to sing songs of lamentation at funerals; they could work at

some few mechanical trades, such as cloth weaving; they could keep a

shop. Occasionally, there was a woman of exceptional talent who made

large profits by means of decorative art; among the wall pictures of

Pompeii there is one which represents a female artist engaged in

painting upon canvas a figure of Bacchus from a statue which serves her

for a model. We read of Iaia, who, though a Greek, lived in Rome and of

whom Pliny says that she was very successful in painting portraits, and

especially in engraving female figures upon ivory. One matron found a

unique occupation; she made large sums yearly by fattening and selling

thrushes for the tables of epicures. But the majority of women who were

able to make a living did so by virtue of their personal attractions and

by ministering to the voluptuousness of the wealthy, as harp players,

dancers, and in other avocations still more questionable.

During the reign of Nero, there were no wars of any great moment. The

old Roman passion for territorial expansion was in abeyance. The

government was concentrated in the person of a man whose ambitions were

histrionic rather than military. Nero was part actor, part clown, wholly

debased; what could be expected from the associates of such a man, or

from the people who tolerated him? If it be true that every nation has

the government of which it is deserving, then the officers and people of

the Roman Empire in Nero's time must be accounted as subordinates and

supernumeraries in a fatuous burlesque which frequently deepened into

mad tragedy. The way to the emperor's favor was not through victorious

conflicts with the enemies of the State, but by means of the lavishment

of fulsome applause of his own imbecile performances in the theatre and

the circus. Nero never entered Rome in military triumph, as had his

predecessors, followed by wagons filled with plunder and a train of

captives who had been formidable to the State; he was content to win

crowns from a debased people who hypocritically admired his voice and

his acting, and to triumphantly enter Rome as conqueror in the Grecian

games. "He made his entry into the city riding in the same chariot in

which Augustus had triumphed. For the occasion he wore a purple tunic

and a cloak embroidered with golden stars, having on his head the crown

won at Olympia, and in his right hand that which was given him at the

Parthian games; the rest were carried in a procession before him, with

inscriptions denoting the places where they had been won, from whom, and

in what plays or performances. A train followed him with loud

acclamations, crying out that they were the emperor's attendants, and

the soldiers of his triumph. He suspended the sacred crowns in his

chambers, about his beds, and caused statues of himself to be erected,

in the attire of a harper, and had his likeness stamped upon coins, in

the same dress. He offered his friendship or avowed open enmity to many,

according as they were lavish or sparing in giving him their applause."

Thus the Roman historian describes the order of that day, and from this

we may judge of the environment of the principal women of Rome in those

times.

Virtue and womanly dignity were inconsiderable qualities in the days of

Nero. The ladies of the court could only attain and hold their positions

by means of their personal attractions and by taking part in excesses

from which every vestige of virtue was eradicated. Prostitution had now

become fashionable. It is possible to give Messalina the benefit of a

doubt as to whether or not she were a mere freak of nature. Agrippina

was monstrously ambitious and as merciless as a tigress whose young are

threatened; but she adopted the only means which her times afforded. In

Poppæa, however, we see the typical woman of decadent Rome--of ordinary

intellect, intensely voluptuous, and devoid of natural affection.

Poppæa was the daughter of that beautiful but wanton lady of the same

name whom Messalina had forced to seek death by her own hand. In this

instance, heredity claimed its vindication; to the daughter descended

the loveliness of person and also the lax principles which characterized

the mother. "This woman," says Tacitus, "possessed everything but an

honest mind. Her wealth was equal to the dignity of her birth; she had a

fascinating conversation, and was not deficient in wit. She observed an

outward decorum, but in her heart was wanton; she rarely appeared in

public, and when she did she wore a veil, either because she did not

want to glut people's eyes with her beauty, or because she thought a

veil became her." It is said of her that she employed all the recipes at

that time known--and they were very numerous--to prevent the inroads

which age will make. She covered her face with a mask when out of doors,

in order to shield it from the sun; and when at last her mirror informed

her that the charms of that face were beginning to wane, she cried: "Let

me die rather than lose my beauty!"--a wish by no means unnatural, for

in the game which she so desperately played her beauty was her only

stake. Nero married her solely for her loveliness of person. The

conjugal fidelity which stands the test of changing years was not then

common; and the law did not enforce it upon the unwilling. Juvenal

doubtless truly pictures the contretemps which women like Poppsea had to

fear:

"Sertorius what I say disproves,

For though his Bibula is poor, he loves.

True! but examine him; and on my life,

You'll find he loves the beauty, not the wife.

Let but a wrinkle on her forehead rise,

And time obscure the lustre of her eyes;

Let but the moisture leave her flaccid skin,

And her teeth blacken, and her cheeks grow thin;

And you shall hear the insulting freedman say:

'Pack up your trumpery, madam, and away!

Nay, bustle, bustle; here you give offence,

With snivelling night and day;--take your nose hence!'"

We have no very trustworthy representation of Poppæa's appearance. There

are in existence medals showing her reputed portrait, especially a Greek

coin with the head of Nero on one side and that of his wife on the

other; but as the former is certainly not a good likeness, it is

Reasonable to suppose that the other is no better. Her face, as it is

here portrayed, is of the ideal Greek type--straight brows, and nose

almost in a line with the forehead. There is also a bust in existence,

which, according to archaeological students, may be held to represent

either the mythical Clytie or the famous wife of Nero. Her hair is said

to have been remarkably beautiful. It was very abundant and of a golden

amber color. Nero composed verses upon it.

There were serious obstacles between Poppæa and the imperial throne

which she speedily manifested an ambition to share--obstacles which, in

more virtuous days, or among women possessing the slightest degree of

modesty, would have been absolutely insurmountable; but with the rulers

of Rome in those times nothing was impossible except self-control for

the sake of honor. Nero was married to Octavia, the daughter of

Messalina and Claudius. Poppæa was also married. She had been divorced

from Rufus Crispinus, a Roman knight, to whom she had borne a son, and

was now joined in matrimony to Otho, the profligate confidant of the

young emperor. There are indications that Otho was fond of his

unprincipled wife. She was the choicest treasure in his magnificently

furnished house. He boasted of her beauty to Nero, and excited the young

ruler's pride as well as his passion by telling him that though he were

the emperor he could not vie with his subject in the possession of such

an example of female loveliness. He even permitted Nero to visit his

wife, but, in his self-esteem, did not count upon the result. Otho

maintained Poppæa in inordinate splendor; but he was not the emperor. He

could give her incalculable riches; but he could not make her the

mistress of the world. Poppæa saw her opportunity. She lavished upon

Nero all the powers of her coquetry; she intimated that she was smitten

with regard for him; she allowed him to flatter himself that he had won

her. But she would hear of nothing but marriage. Nero was at her feet;

but, having so far attained her end, she would listen to no

protestations until he removed all hindrances to their union. She would

be empress or nothing. With her beauty for a bait, she led Nero on to

the committal of the most heinous crimes. Agrippina was murdered because

Poppæa taunted Nero with being under the care of a governess. "Why did

he delay to marry her?" Tacitus represents her as asking. "Had he

objections to her person or her ancestry? Or was he dissatisfied because

she had given proof of her fertility? Did he doubt the sincerity of her

affection? No; the truth must be that he was afraid that if she were his

wife she would expose the insolence and the rapaciousness of his mother.

But if Agrippina would bear no daughter-in-law who was not virulently

opposed to her son, she desired to be sent to Otho. She was ready to

withdraw to any quarter of the earth, rather than behold the emperor's

degradation." Otho, in order that he might be out of the way, had been

appointed Governor of Lusitania.

It was some time after the death of Agrippina before Octavia was

removed, first by repudiation and then by death. We shall have occasion

to notice the character of this estimable woman in a later chapter. In

the meantime, the emperor did not have to wait wholly unrewarded by the

favors of Poppæa. He was entirely under her influence; but the memory of

the remorse which had seized him after the murder of his mother

restrained him, for a while, from adding to that crime another of equal

atrocity. Again, however, Poppæa cunningly worked upon his fears,

insinuating that unless he reinstated Octavia, whom he hated, as

empress, the people would give her another husband, whom they would make

emperor. This sealed Octavia's doom; shortly afterward, her head was

brought to Rome and laid at the feet of her infamous successor, Poppaea

was at last the empress in name as well as in fact; and when she

presented Nero with a daughter, he made a mockery of the title by naming

ner, as well as the child, Augusta. But the little one soon died, and

the Senate was obliged to console the father by decreeing that his

infant daughter had become a goddess.

All the historians agree that subsequent to his connection with Poppæa,

Nero deteriorated in his character, or at least in his conduct. The

influence of the woman seemed to bring out and encourage the worst that

was in him. For Poppæa, however, there was compensation; her principal

gain, in her own estimation, may perhaps be best typified by the palace

which Nero built. She cared little for political power; imperial

magnificence was the attraction that enticed her. Surely never did woman

have her wish in this respect so completely gratified as did the wife of

Nero! He built himself a house, having first destroyed many another in

order to furnish a site. The author of Rome of To-day and Yesterday

says: "It was upon the palace for the emperor that Severus and Celer,

the first architects ever mentioned by name in Roman history, lavished

all the resources of his boundless wealth and their skill. It seems so

extravagant to say that the Golden House extended over an area of nearly

a square mile in the very midst of the city, that if there had not been

left, from point to point, remains of it over a considerable part of

this area, the statement of the old writers to that effect would not

have seemed worthy of belief." By the Golden House is, of course, not

meant one continuous building; but there was an enclosure by means of

three colonnades, each a mile in length, and an entrance portico

somewhat narrower on the side opposite the Forum. Within this enclosure

were great courts resembling parks, fountains, and fishponds, besides

the residence buildings and baths. "In parts," says Suetonius, "this

house was entirely overlaid with gold and adorned with jewels and

mother-of-pearl. The supper rooms were vaulted, and compartments of the

ceilings, inlaid with ivory, were made to revolve and scatter flowers;

moreover, they were provided with pipes which shed essences on the

guests. The chief banqueting room was circular, and revolved

perpetually, night and day, in imitation of the motion of the celestial

bodies. The baths were supplied from the sea and from Albula. Upon the

dedication of this magnificent house, when finished, all Nero said in

approval of it was: 'Well, now at last I am housed as a man should be!'"

Amidst this magnificent splendor, Poppæa lived. We will endeavor to

recount her manner of living as closely as we may, in order that we may

know what was the ideal existence in the estimation of the majority of

the women of her time.

The chief concern of Poppæa, as of all the women of that period whom age

or nature had not unkindly relieved of this responsibility, was the

preservation of her beauty. The Roman authors have mercilessly laid bare

the methods and mysteries to which their ladies resorted for this

purpose. No pains or discomforts were avoided in order to retain the

freshness of complexion which was apt, in the dissipated life of the

palace, quickly to disappear. Poppæa is reputed to have invented many

cosmetics and face washes, and especially a mask which was worn at

night, which was composed of dough mixed with ass's milk; while for the

purpose of removing wrinkles another mask, composed of rice, was worn,

Juvenal mocks at the appearance of the ladies with their faces thus

encased, "ridiculous and swollen with the great poultice." He suggests

that what is fomented so often, anointed with so many ointments, and

receives so many poultices, ought to be considered a sore rather than a

face. It was held to be of great importance that these applications

should be washed off with ass's milk, and the old writers assert that

Poppæa kept large herds of these animals in order that she might bathe

in their warm milk every day. The Roman ladies were by no means averse

to assisting nature in augmenting their charms; they used white and red

paints with artistic effect. These were ordinarily moistened with

saliva, possibly on account of the Roman superstition in regard to the

efficacy of lustration. The brows and eyelashes were frequently dyed;

and so careful were the women to render nature all the assistance

possible, that even the delicate veins of the temples were heightened in

their effect by a faint touch of blue. The teeth had always received

most careful attention. There were many pastes and powders known to the

Roman beauty. Artificial teeth made of ivory had been in use from very

ancient times, for in the laws of the Twelve Tables there was one which

prohibited the deposition of gold in the graves of the dead, excepting

the material used for the fastening of false teeth. "You have your hair

curled, Galla," says Juvenal, "at a hair dresser's in Suburra Street,

and your eyebrows are brought to you every morning. At night, you remove

your teeth as you do your dress. Your charms are enclosed in a hundred

different pots, and your face does not go to bed with you." Many

instances are recorded of the costliness of the attire of these Roman

ladies. They wore silk which was sold at its weight in gold. There was a

kind of muslin so transparent that it was known as "woven air." Tunics

were ornamented with figures embroidered in gold thread, and encrusted

with pearls and precious stones. Pliny relates that he saw Lollia

Paulina wearing a dress which was covered with emeralds and pearls from

her head to her feet. She carried with her the receipts to show that

upon her person she wore a value of forty million sesterces; and this

was not her best dress, for the occasion was only a second-class

betrothal feast. At an entertainment given by Claudius on Lake Fucinus,

Agrippina wore a garment which was woven entirely of gold thread.

The women of Poppæa's day seem to have been fully acquainted with the

benefits to be derived from physical exercise. Agrippina, as we have

seen, could swim with no less expertness than Cloelia of ancient renown.

Indeed, Juvenal pictures the women breaking the ice and plunging into

the river in the depth of winter, and diving beneath the eddies of the

Tiber at early dawn. This, however, was for religious and propitiatory

reasons. The same satirist refers with evident disapproval to women

exercising with heavy dumb-bells in the same fashion as did the men when

preparing for the bath. It is apparent that in this age women deemed it

to be in keeping with their rights to share, as closely as nature would

permit, in the pursuits and the privileges of the men; just as there

were men who, beyond the boundary set by nature, usurped the position

which belonged to women.

We have spoken of the bath; and it being so large a feature in Roman

city life and so good an illustration--though the most innocent--of the

luxury of the times, it will not be amiss to afford a little space to

its description.

The Golden House and many of the palaces of the wealthy contained baths

which, while not on so large a plan as the public thermæ, were

doubtless even more luxuriously appointed. We will take, however, the

public baths for our example. In the period of the early Republic, the

Romans, though scrupulously cleanly as the warmth of their country

required, contented themselves with washing in the Tiber. Every ninth

day was deemed sufficient for a complete immersion. As the arts of

civilization advanced, tubs were placed in the houses, and a daily bath

before the evening meal became customary. The first aqueduct for the

conveyance of water into the city was built by Appius Claudius about

B.C. 310. Seven or eight others were afterward constructed, notably that

of Agrippa; so that no city was ever better supplied with water than was

ancient Rome. This made possible the public baths, which early made

their appearance and which must have been such a boon to the people. At

first these baths were solely for lavatory purposes, and were neither so

magnificent nor so much a social feature as they afterward became.

Seneca relates that at first the ædiles superintended not only the

decorum of the bathers, but also the temperature of the baths. Under

Augustus, these public conveniences began to be characterized with that

magnificence of structure in which all the emperors delighted. A great

many of these buildings were erected in various parts of the city; as

many as eight hundred have been enumerated. Some of these were

marvellous, not only for their dimensions, but also for the costliness

of the material and the artistic decorations. The baths of Caracalla

were adorned with two hundred columns of the finest marble and furnished

with sixteen hundred seats of marble, and it is said that eighteen

thousand persons might conveniently bathe there at one time. Yet these

were excelled both in size and magnificence by the Thermæ Dioclesianæ.

The gift of these establishments was one of the means by which the

emperors kept themselves in favor with the people. For a trifling sum, a

citizen of any degree could repair to this scene of magnificence and

luxury, where there were crowds of slaves to minister to his comfort in

a style which might arouse the envy of the proudest Oriental monarch.

Besides the various kinds of hot and cold baths, swimming tanks, etc.,

there were stately porticoes for games and exercise, there were

gymnasiums, magnificent galleries for the exhibition of specimens of

painting and sculpture, and frequently there were libraries where the

studious might rest and read after the refreshing luxury of the baths.

The bathrooms proper were duplicated in each establishment, one part

being open for the use of the men, the other set apart for the women.

There is a hint, however, that, during the reign of some of the worst of

the emperors, this propriety was not always strictly adhered to. Unless

the Latin writers wilfully calumniate their own times, it was not a

thing unknown for both men and women, in the private baths of palatial

residences, to be waited on by slaves of the opposite sex.

Whether or not Poppæa condescended to make use of the public baths, it

is impossible to ascertain. It is certain, however, that the emperors

frequently joined the multitude in their sports and lavations. At two

o'clock each day, the opening of the baths was announced by the ringing

of a bell. Everybody repaired thither; it was the common rendezvous for

gossip, recreation, and amusement. Authors frequently read at the baths

their new productions to those of the crowds who cared to listen. Much

of the afternoon was spent in this manner. Before taking the bath,

exercise was indulged in, a favorite form of which was ball playing.

Then one entered the caldarium, in which hot air was diffused by means

of pipes leading from a furnace in the basement; then came the

tepidarium, always followed by a plunge in cold water. While bathing,

the skin was rubbed or scraped with a silver instrument called a

strigula. The Romans concluded the toilet by rubbing the body with

odoriferous ointments, and, thus refreshed and anointed, proceeded to

the banquet.

In the early days of the Republic, meals were prepared with care, but

there was no sumptuousness, no art. The first signs of Asiatic luxury

made themselves noted on the table; delicacy and profusion were carried

to excess, resulting in extravagance and gluttony. The cook, who had

anciently been the lowest of the slaves, came to be the most important

officer in the establishments of the rich; that which at first was only

a low and necessary employment came to be a difficult and a highly

esteemed art. The price of a cook, says Pliny, was rated at as much as

would have formerly sufficed for the expense of a triumph, and a fish

was bought at the price anciently paid for a cook.

To make provision for banquets seems to have been more the province of

the master of a Roman house than it was that of the mistress. There is a

great contrast between the position of a Roman matron and that of a

modern lady in this respect; the responsibility for the entertainment of

guests did not so peculiarly rest upon the former as it does upon the

latter. We frequently read of banquets given by men in the account of

which no mention whatever is made of the wife, and these were ordinary

occasions when there can be no doubt as to her presence. The guests were

usually invited solely in the master's name. In Petronius's account of

Trimalchio's Feast, he represents one guest asking another who is the

woman that so often scuttles up and down the room. He is told that she

is Fortunata, Trimalchio's wife, that she counts her money by the

bushel, but that she has an eye everywhere, and when you least think to

meet her she is at your elbow. Her propensity for petty management seems

to have been stronger than her love for the entertainment; for another

visitor coming in later asks "why Fortunata sits not among us?" The host

replies: "Till she has gotten her plate together and has distributed

what we leave among the servants, not a sup of anything goes down her

throat." But that this was unusual is shown by the inquirer threatening

to leave unless the mistress sat down with them.

We have elsewhere described the Roman dining hall, or triclinium.

Doubtless the Golden House had many of these splendid salons. Lucullus,

who was famous for the enormous expense at which he lived, called each

of his numerous dining halls by the name of some divinity, and every

hall had a set rate of expense at which an entertainment in it was

given; so that when he ordered his household steward to prepare a

banquet in a certain salon, the servant knew exactly what to provide and

at how great a cost his master wished to entertain. It is told that

Cicero and Pompey once met Lucullus in the Forum and invited themselves

to supper with him. They declared that they wished to share the meal of

which he himself would partake if he were without company, and they

would not allow him to give any directions to the servants, only

permitting him to order his steward to prepare the table in the

Triclinium Apollo. The man knew exactly what to do, and the supper was a

great surprise to the guests, for a banquet in that hall was never

served at an expense of less than fifty thousand drachmas [nearly nine

thousand dollars].

In order that we may obtain as complete a picture as possible of the

Roman woman's life, we must attend in imagination one of those banquets

which she attended in reality.

On entering the dining hall, we notice that around the table,--or

tables, for there will be many if the company is a large one,--in place

of chairs, are couches with an abundance of soft pillows. These couches

are placed on three sides of the table; for it was the custom of the

Romans to recline at their meals. When this custom was first introduced

from Asia, the women did not think that it comported with their modesty

to adopt this new style, and until the end of the Republic they retained

the old habit of sitting at table, while the men lay on the couches; but

at the time of Poppæa women had entirely relinquished this relic of

their former scrupulousness of demeanor and were accustomed to follow

the habit for which the lassitude resulting from the bath prepared them

and which these prolonged feasts made necessary for comfort.

Having taken our places at the table, our attention is first drawn to

the fact that all the slaves, as they move about the room on their

various errands, are singing in a low voice. This is the custom of the

house; at the banquet everything must be done to the sound of music. All

the guests receive a crown or a wreath of flowers, which is worn upon

the head during the feast. Roses are to be seen everywhere in great

profusion. We are first served with some dishes which are designed to

excite rather than appease the appetite; these consist of dormice

covered with honey and pepper, hot sausages, and a large pannier filled

with both white and black olives. On the dishes in which these viands

are served we notice not only the host's name, but also the number of

ounces of silver of which the utensils are composed. An ostentatious

display of excellence was always sought after by the Romans.

A banquet must always begin with eggs; so, having picked a little of the

afore-mentioned dainties to sharpen our hunger, the repast really

commences. A table is brought in, on which we see a large hen, carved in

wood, sitting as on a nest. The slaves search in the straw and bring

forth the eggs, which are handed around. The host, after examining these

simple articles of diet, says that he commanded to have them placed

under a hen for a short time, but he is afraid that they are half

hatched. Just as we are inclined to put ours aside, we discover that

what appears to be the shell is nothing but paste, and, breaking it

open, find inside a delicately cooked little bird of the wheatear

species. We must be prepared for such culinary surprises. Then the music

strikes up, and the slaves clear the table, dancing instead of walking.

If a slave drops a valuable dish, she will not be scolded so much for

the loss as she will be if she stops to pick up the fragments, as though

the loss were of consequence. Wine is now brought in. It is contained in

sealed glass vessels, each with a label setting forth the age of the

vintage. Wine is plentiful; it is even passed to us in place of water in

which to wash our hands.

Now the viands are brought on in bewildering variety; and the marvellous

conceits of the cook baffle description. Here is an immense silver

charger, around which are carved the signs of the zodiac; and upon each

sign there is something suited to it, either in reality or its image in

pastry: a lobster, a goose, two pilchards, etc. There is a splendid

fish, and upon the sides of the dish are four little images which spout

a delicious sauce.

There must also be somewhat to amuse us; for this banquet is to be of

long continuance, and there is a limit to one's eating. A lengthy

interval occurs, during which a company of actors, women as well as men,

take their places in the lower part of the hall, which is left clear for

the purpose, and there enact a farce which ridicules the follies of the

times and causes us much laughter. Other women perform upon the harp;

some exhibit their marvellous acrobatic skill; and one girl, clothed

only in a diaphanous, silky robe which reveals more of her person than

it hides, performs a dance which is as remarkable for its grace as for

its immodesty. We may be glad that we are not treated to a gladiatorial

combat, as has sometimes been the case in this same house.

After these entertainments have been concluded, an enormous dish is set

before us, and in it a great boar. On his tusks hang two baskets, one

filled with dates, the other with almonds. About him are little pigs

made of sweetmeats. They are presents which we are to carry away with

us; for it is always the custom for the men at a banquet to carry some

part of it home to those women of their families who have not been

present. To our great astonishment, when the servant makes a hole in the

side of this boar, as though to carve it, there fly out a number of

blackbirds, which continue to flutter about the room until they are

again captured.

While we are beguiling our time with wine and conversing with the ladies

present, a large and entire hog is brought upon the table. Whereupon our

host, having examined the animal closely, expresses it as his belief

that it has not been disembowelled by the cook. That officer being sent

for, he confesses that in his haste that part of the preparation had

truly been forgotten. He is ordered to be flogged, and the executioners

prepare to carry out the command upon the spot in the presence of us

all; but mercy is implored for him by the women, and his master contents

himself by ordering him to finish his work there upon the table. At

this, the cook takes a knife and cuts open the hog's belly, and there

immediately tumble out a heap of delicious sausages of various kinds and

sizes. This done, all the slaves cheer their master, and a present of

silver is made to the cook.

While we are discussing this and the various other interesting episodes

of the feast, we are startled by the ceiling giving a great crack, and,

as we gaze up in considerable alarm, the main beam opens in the middle.

A large aperture appears, from which descends a great disk and upon it

are hung many beautiful presents for the guests, also fruits of various

kinds which when touched throw out a delicious liquid perfume.

Thus, eating and conversing and viewing these wonders and the various

performances of the entertainers, the feast begun in the early evening

has endured until the night has grown late. Wine has been flowing

without stint, and its effect is to be seen among the company. The

ladies present have indulged with almost as great freedom as the men.

Tongues have become loosened and stories are told and allusions made

which might bring the blush to some cheeks, were they not already

flushed with wine. The feast is likely to end in a revel. Men take the

wreaths of flowers from the heads of the women and dip them in the wine,

which they then drink as a mark of gallantry. There is no longer need

for the actors and female entertainers; the male guests play the

buffoon, and matrons, throwing aside their robes, dance, though possibly

with less grace, certainly with no more modesty than did the

professional women who had been hired for that purpose. Pranks are

played upon those who have fallen into an intoxicated stupor. Some are

roaring bacchic songs, some are loudly arguing concerning politics,

giving vent to opinions for which they may have to give an account to

the emperor on another day; some are brawling, while others are

conversing with the women in such unrestrained fashion as leaves no room

for wonder at the numerous matrimonial readjustments which are

characteristic of these times.

These are some of the features of such banquets as those to which the

women of Poppæa's time were accustomed. We have drawn our description

principally from Petronius's inimitable account. Though in Trimalchio's

Feast there was, so far as it appears, no other woman besides his wife,

yet we know from other sources that the presence of women at such

entertainments was common. There is no evidence to the effect that they

were in the habit of leaving the triclinium before the unrestrained

indulgence in wine had made their presence there entirely inconsistent

with any ideas of strict propriety; indeed, if the poets are to be

credited, it often happened that love making of an ardent nature was

carried on in the confusion which marked the termination of these

feasts.

Poppæa had married an imperial actor. Even at so late a period as the

days of Julius Cæsar, a citizen lost his civic rights by appearing on

the stage; but now the whole Roman Empire bent in fulsome adulation

before a crazy ruler who strained a wretched voice to sing Canace in

Labor. The Forum had become silent; the temples were frequented, but

with little faith or sincerity on the part of the worshippers. The

public life of Rome centred in the theatre and the circus. "After the

market place has been designed," says Vitruvius, "a very healthy spot

must be chosen for the theatre, where the people can witness the dramas

on the feast days of the immortal gods." In the days of Nero, the Roman

people did not wait for a religious motive in order that they might

indulge in shows which were certainly morally unhealthy, however

salubrious may have been the site of the theatre. The most popular and

best remunerated public servants were actors and actresses, dancing

women and female musicians. Mommsen, commenting on the condition of

theatrical art at an earlier time than that of Nero, says: "There was

hardly any more lucrative trade in Rome than that of the actor and the

dancing girl of the first rank. The princely estate of the tragic actor

Æsopus amounted to two hundred thousand pounds sterling; his still more

celebrated contemporary Roscius estimated his annual income at six

thousand pounds, and Dionysia the dancer estimated hers at two thousand

pounds." Later he adds, as indicating what was popular at the time: "It

was nothing unusual for the Roman dancing girls to throw off at the

finale the upper robe and to give a dance in undress for the benefit of

the public."

There is in existence an epitaph of a girl named Licinia Eucharis, who

is reputed to have been the first female to appear on the public Greek

stage in Rome. She died at the age of fourteen; but, notwithstanding her

tender years, she was "well instructed and taught in all arts by the

Muses themselves."

The theatrical displays of the Romans had always been characterized by

vulgarity and coarseness. The ancient Atellan farces were as full of

obscenity as were the fescennine songs of broad allusions. This being

so, even in the days when the Roman people deified chastity, it

naturally follows that unbounded license must have prevailed in the

degenerate days of the Empire. The surfeited taste of the licentious

populace was gratified by hordes of women as well as men, who strove to

give new piquancy to their exhibitions by the shamelessness of their

performances.

There is some evidence, however, to show that now and again there was an

actress who endeavored to "elevate the stage." Horace reports that when

Arbuscula was hissed by the people, though doubtless she was giving a

good performance, she had the courage to retort: "It is enough for me

that the knight Mæcenas applauds"; but such a spirit was unusual, and

the Roman theatre continued to deteriorate. As is always the case in

such matters, the demand created the supply; but the supply also renewed

and strengthened the taste from which sprung the demand. Watching some

gladiators who had been condemned to mortal combat, a Roman argued with

Seneca that they were criminals and deserved their fate. "Yes," answered

the philosopher; "but what have you done that you should be condemned to

witness such an exhibition?"

The moralist's stricture on their amusements was not concurred in by the

great mass of his female compatriots. Patrician and plebeian, rich and

poor, the women of Rome craved the realistic scenes of the theatre and

the terrible excitements of the circus with as much avidity as did the

men. Augustus had ordered that women should not be present at the

exhibitions of wrestlers, and that they should only be allowed to

witness gladiatorial combats from the upper and remote part of the

theatre; but in the days of Nero, the sex was placed under no such

restrictions. Augustus also severely punished an actor who allowed a

married woman, dressed as a boy, to wait upon him at table; but

afterward it became common for patrician ladies to be the paramours of

gladiators and pantomimists, with no fear of punishment save the

immortal lashings of the poetic satirists. These lashings, it is

evident, had no deterrent effect; despite the sarcasms of Juvenal, the

Ælias and Hispullas continued to be enamored of tragic actors. Hippia,

though the wife of a Senator, accompanies a gladiator to Alexandria. She

dines among the seamen, walks the deck in a rolling sea, and delights to

take a hand at the ropes. What was the attribute that captivated her?

Sergius was not handsome; "but then, he was a swordsman. The sword made

its wielder as beautiful as Hyacinthus. It was this she preferred to her

children, her native land, and her husband. It is the steel of which

women are enamored. This same Sergius, if he were discharged from the

arena, would be no better than her husband in her eyes."

In the times of the most dissolute emperors, the people of Rome lived

chiefly to attend the theatre and the circus; after bread, all they

asked for was shows. There were theatres in Rome capable of seating

eighty thousand persons. We may imagine such a concourse waiting while

Nero dines in their presence in the imperial box, and allays their

impatience by shouting: "One more sup, and then I will present you with

something that will make your ears tingle." But it is likely that the

Roman ladies of noble birth were wont to hear the announcement of Nero's

performances with little anticipatory pleasure. They dared not absent

themselves, for there were spies who would report to the emperor their

failure to attend; and, being present, they were compelled to submit to

the infliction of the whole of the wretched exhibition; for on such

occasions the doors were absolutely closed against all egress. So

thoroughly was this rule carried out that there are reports of infants

having been born in the theatre while Nero was displaying his skill as

an actor. More than that, it was never known when or under what

circumstances the lightning of his malicious displeasure would fall upon

some unlucky head. Once, when he was playing and singing in the theatre,

he observed a married lady dressed in the shade of purple which he had

prohibited. He pointed her out to his officers, and she was not only

stripped of her raiment, but her property was also practically

confiscated by means of fines.

Yet doubtless the fact that they were afforded the strange privilege of

witnessing the acting of an emperor did serve to arouse the interest of

the blasé Roman populace. Legitimate histrionic art had become for them

tiresome, as it always does where luxury and pampered idleness tend to

blunt the artistic conscience. Nothing less than libidinous vaudeville,

in which matrons of noble birth were by bribes or threats induced to

take part, could create the least sensation. Realistic performances were

more popular still. The actors in these were found in the dungeons,

therefore they were not costly and required little training. A much

truer idea of agony is obtained by watching a man really suffer than by

seeing it mimicked by an actor; and if the piece to be staged includes a

death, why not provide the audience with the opportunity of seeing a

criminal die in the manner designated? These were the scenes to which

the women of Rome grew accustomed, with the result that, for the

evil-disposed, bloodshed was no more than a pastime, while for the

better-natured it at least enabled them to look upon their own death

with diminished terror. But the favorite exhibition with the Roman

populace was the sanguinary gladiatorial encounter. Ten thousand men

were constantly kept and trained, that the people might witness their

combats to the death with each other or with ferocious animals. These

combats were to be seen in greater perfection at a later day than that

of Poppæa, in the Colosseum--the most stupendous show place ever erected

by man, and in which was exemplified the most enormous wickedness that

has disgraced the name of humanity. In the central space was "the sand,"

the arena, often red and soaked like a battlefield with human blood.

Around this was a gilded fence to prevent the animals or the more

desperate men from rushing with deadly hate upon the unfeeling audience.

Behind that stood the marble podium, on which were placed the imperial

seats and those of the nobility. Then came, tier above tier, the seats

of the commoner people, who ofttimes made the vast edifice resound with

their roar--more dreadful than that of the forest king: "To the lions!"

In the front seats and behind them sat women, beautiful of face but

hardened in disposition, who, when a man was mortally wounded, cried:

"hoc habet [he has it!]" with an excitement as unsympathetic as that

which delighted their male companions; and who, when an unfortunate

combatant lowered his arms in token of defeat, were as likely to point

their thumbs downward, in sign that the unfortunate man was forthwith to

be despatched, as to raise them in token of mercy.

So long as Petronius, the man of taste, was the "arbiter" of Nero's

amusements, the people of Rome were not called upon to witness the most

outrageous examples of imperial depravity. Yet it must be confessed

that, if the women described in the Satyrikon are to be accepted as

being typical of the majority of the Roman ladies, their morals could

not suffer much by the influence even of a Nero. Tigellinus incited the

emperor to greater lengths of profligacy than he otherwise would have

reached. Tacitus describes the feast given by Tigellinus, for which "he

built, in the lake of Agrippa, a raft which supported the banquet, which

was moved to and fro by other vessels drawing it after them. He had

procured fowl and venison from remote regions, and fish from far-off

seas. Upon the margin of the lake were erected brothels, filled with

ladies of distinction, and over against them other women whose

profession was apparent by the scantiness of their attire. As soon as

darkness came on, the surrounding dwellings echoed with the music, and

in the groves brilliant lights revealed everything that was obscene and

improper."

During the reign of the dissolute emperors, the virtue of women was but

little respected. Nero denied that any person was sincerely chaste. If a

woman of any social prominence in those days desired to retain her

honor, her beauty was her greatest misfortune. No ties or obligations,

not even the sanctity of the Vestals, were respected by the lustful

tyrants. If a man rejoiced in a beautiful and modest wife, she might

any day be requested to appear at the palace; and the husband, if he

would preserve his life, was compelled to bear the dishonor in silence.

Occasionally, however, there was a woman who showed more spirit;

Mallonia publicly upbraided Tiberius for his wickedness, and then went

home and killed herself. But the condition of morals was such that there

were a great many wives and husbands who did not regard such tyranny

with any special degree of horror. Piso, who was put to death for his

conspiracy against Nero, had robbed his friend Domitius Silius of his

wife, who was, the historian informs us, a depraved woman and void of

every recommendation but personal beauty; but "both concurred, her

husband by his passiveness, she by her wantonness, to blazon the infamy

of Piso."

Among these characters there was but little of that chaste love which

glorifies the marriage bond. Poppæa could have had no regard for the

despicable Nero; her sole concern was that she might be empress, and

maintain herself in that exalted position. The emperor prized nothing in

his wife except her incomparable beauty; and he placed her beside

himself on the throne only because it was necessary that Cæsar should

have legitimate heirs.

As to the character of Poppæa, Josephus credits her with being very

religious, and Tacitus says that she was much given to consulting with

soothsayers and eastern charlatans. Yet it may have been that,

notwithstanding her wild profligacy and shameless ambition, Poppæa felt

the vacuity of the glittering show by which she was surrounded, and that

at times a restless conscience compelled her to grope among the tangled

mysteries of the spiritual life. At the same time, it has been

suspected--and the suspicion is not totally without warrant--that the

Roman Jews, in their bitter animosity against the Christians, were

aided by the empress in instigating that persecution which rendered the

reign of Nero so superlatively infamous.

It was rare for an imperial consort to come to other than a violent end;

and Poppæa was no exception to the rule. Her death was the act, though

unpremeditated, of her husband. One day, she found fault with him for

returning later than she desired from a chariot drive. Angered by her

upbraidings and brutal by nature, he kicked her, and, being in a

condition of pregnancy at the time, she shortly afterward died of the

blow. It is said that her body was not consumed by fire, as was the

custom of the Romans, but embalmed in Jewish fashion and placed in the

tomb of the Julian family. She was, however, given a splendid funeral;

and there is no stronger witness to the terrible moral apathy which

characterized the times than the fact that her murderous husband

delivered on the occasion a laudatory oration. From the rostrum, he

magnified "her beauty and her lot, in having been the mother of an

infant enrolled among the gods." There being nothing else in her

character to extol, he treated her gifts of fortune as having been so

many virtues. It is impossible to doubt that the ancient historian is

correct when he asserts that though the people were obliged to put on an

appearance of mourning, they could but rejoice at the death of this

woman, when they remembered her lewdness and her cruelty; and although,

as Pliny tells us, all Arabia did not produce in a whole year as many

spices as were consumed at the funeral of Poppæa, there was no incense,

material or eulogistic, by which it was possible to overcome the evil

odor of her life.

The reign of Nero was typical of other ages that were to follow. The

Roman people were to drink still deeper of the dregs of servility, and

they were to become yet more morally apathetic, before they would awaken

to better things. Poppæa was simply a woman of her time, and she was

followed by generations of women, both of high and low degree, who were

like-minded with herself. Imperial prostitutes and plebeian courtesans

run riot through all the long drawn out decadence of the Roman Empire;

but, although a veritable picture of the Roman woman could not be given

without the inclusion of such types as those delineated in this and the

preceding chapter, we will at least spare ourselves and the reader

further recital of vice and crime by confining the exemplification to

this one period. We have not refrained from including the worst features

and employing the darkest colors that history warrants, in order that,

to use the expression of Tacitus, we may not have to repeat instances of

similar extravagance.

Although Nero was a monster of iniquity, he was not denied the

disinterested love of women. That strange, strong passion which holds

woman's heart to the most unworthy objects and feeds itself with

idealizations made the name of Nero dear to some when it was execrated

by all the world besides. And when at last he was driven from the

throne, and, uttering the words: "I yet live, to my shame and disgrace,"

drove the suicidal dagger through his throat, there were women who

tenderly cared for that body which sycophantic courtiers extolled while

it lived and neglected when it was dead and powerless. His nurses Ecloge

and Alexandra, who had cared for him when he was an innocent boy, and

that Acte who had been his first love and who had never entirely lost

her influence over him, laid his ashes in the tomb of his fathers, and

grieved over a death which gave to the world at large great cause for

rejoicing.

Prev

| Next

| Contents