Second Reign of Chosroes II. (Eberwiz). His Rule at first Unpopular, His Treatment of his Uncles, Bindoes and Bostam. His vindictive Proceedings against Bahram. His supposed Leaning towards Christianity. His Wives, Shirin and Kurdiyeh. His early Wars. His Relations with the Emperor Maurice. His Attitude towards Phocas. Great War of Chosroes with Phocas, A.D. 603-610. War continued with Heraclius. Immense Successes of Chosroes, A.D. 611-620. Aggressive taken by Heraclius A.D. 622. His Campaigns in Persian Territory A.D. 622-628. Murder of Chosroes. His Character. His Coins.

The second reign of Chosroes II., who is commonly known as Chosroes Eberwiz or Parwiz, lasted little short of thirty-seven years—from the summer of A.D. 591 to the February of A.D. 628. Externally considered, it is the most remarkable reign in the entire Sassanian series, embracing as it does the extremes of elevation and depression. Never at any other time did the Neo-Persian kingdom extend itself so far, or so distinguish itself by military achievements, as in the twenty years intervening between A.D. 602 and A.D. 622. Seldom was it brought so low as in the years immediately anterior and immediately subsequent to this space, in the earlier and in the later portions of the reign whose central period was so glorious.

Victorious by the help of Rome, Chosroes began his second reign amid the scarcely disguised hostility of his subjects. So greatly did he mistrust their sentiments towards him that he begged and obtained of Maurice the support of a Roman bodyguard, to whom he committed the custody of his person. To the odium always attaching in the minds of a spirited people to the ruler whose yoke is imposed upon them by a foreign power, he added further the stain of a crime which is happily rare at all times, and of which (according to the general belief of his subjects) no Persian monarch had ever previously been guilty. It was in vain that he protested his innocence: the popular belief held him an accomplice in his father's murder, and branded the young prince with the horrible name of "parricide."

It was no doubt mainly in the hope of purging himself from this imputation that, after putting to death the subordinate instruments by whom his father's life had been actually taken, he went on to institute proceedings against the chief contrivers of the outrage—the two uncles who had ordered, and probably witnessed, the execution. So long as the success of his arms was doubtful, he had been happy to avail himself of their support, and to employ their talents in the struggle against his enemies. At one moment in his flight he had owed his life to the self-devotion of Bindoes; and both the brothers had merited well of him by the efforts which they had made to bring Armenia over to his cause, and to levy a powerful army for him in that region. But to clear his own character it was necessary that he should forget the ties both of blood and gratitude, that he should sink the kinsman in the sovereign, and the debtor in the stern avenger of blood. Accordingly, he seized Bindoes, who resided at the court, and had him drowned in the Tigris. To Bostam, whom he had appointed governor of Rei and Khorassan, he sent an order of recall, and would undoubtedly have executed him, had he obeyed; but Bostam, suspecting his intentions, deemed it the wisest course to revolt, and proclaim himself independent monarch of the north country. Here he established himself in authority for some time, and is even said to have enlarged his territory at the expense of some of the border chieftains; but the vengeance of his nephew pursued him unrelentingly, and ere long accomplished his destruction. According to the best authority, the instrument employed was Bostam's wife, the sister of Bahram, whom Chosroes induced to murder her husband by a promise to make her the partner of his bed.

Intrigues not very dissimilar in their character had been previously employed to remove Bahram, whom the Persian monarch had not ceased to fear, notwithstanding that he was a fugitive and an exile. The Khan of the Turks had received him with honor on the occasion of his flight, and, according to some authors, had given him his daughter in marriage. Chosroes lived in dread of the day when the great general might reappear in Persia, at the head of the Turkish hordes, and challenge him to renew the lately-terminated contest.

He therefore sent an envoy into Turkestan, well supplied with rich gifts, whose instructions were to procure by some means or other the death of Bahram. Having sounded the Khan upon the business and met with a rebuff, the envoy addressed himself to the Khatun, the Khan's wife, and by liberal presents induced her to come into his views. A slave was easily found who undertook to carry out his mistress's wishes, and Bahram was despatched the same day by means of a poisoned dagger. It is painful to find that one thus ungrateful to his friends and relentless to his enemies made, to a certain extent, profession of Christianity. Little as his heart can have been penetrated by its spirit, Chosroes seems certainly, in the earlier part of his reign, to have given occasion for the suspicion, which his subjects are said to have entertained, that he designed to change his religion, and confess himself a convert to the creed of the Greeks. During the period of his exile, he was, it would seem, impressed by what he saw and heard, of the Christian worship and faith; he learnt to feel or profess a high veneration for the Virgin; and he adopted the practice, common at the time, of addressing his prayers and vows to the saints and martyrs, who were practically the principal objects of the Oriental Christians' devotions. Sergius, a martyr, hold in high repute by the Christians of Osrhoene and Mesopotamia, was adopted by the superstitious prince as a sort of patron saint; and it became his habit, in circumstances of difficulty, to vow some gift or other to the shrine of St. Sergius at Sergiopolis, in case of the event corresponding to his wishes. Two occasions are recorded where, on sending his gift, he accompanied it with a letter explaining the circumstances of his vow and its fulfilment; and even the letters themselves have come down to us, but in a Greek version. In one, Chosroes ascribes the success of his arms on a particular occasion to the influence of his self-chosen patron; in the other, he credits him with having procured by his prayers the pregnancy of Sira (Shirin), the most beautiful and best beloved of his wives. It appears that Sira was a Christian, and that in marrying her Chosroes had contravened the laws of his country, which forbade the king to have a Christian wife. Her influence over him was considerable, and she is said to have been allowed to build numerous churches and monasteries in and about Ctesiphon. When she died, Chosroes called in the aid of sculpture to perpetuate her image, and sent her statue to the Roman Emperor, to the Turkish Khan, and to various other potentates.

Chosroes is said to have maintained an enormous seraglio; but of these secondary wives, none is known to us even by name, except Kurdiyeh, the sister of Bahram and widow of Bostam, whom she murdered at Chosroes's suggestion.

During the earlier portion of his reign Chosroes seems to have been engaged in but few wars, and those of no great importance. According to the Armenian writers, he formed a design of depopulating that part of Armenia which he had not ceded to the Romans, by making a general levy of all the males, and marching them off to the East, to fight against the Ephthalites; but the design did not prosper, since the Armenians carried all before them, and under their native leader, Smbat, the Bagratunian, conquered Hyrcania and Tabaristan, defeated repeatedly the Koushans and the Ephthalites, and even engaged with success the Great Khan of the Turks, who came to the support of his vassals at the head of an army consisting of 300.000 men. By the valor and conduct of Smbat, the Persian dominion was re-established in the north-eastern mountain region, from Mount Demavend to the Hindu Kush; the Koushans, Turks, and Ephthalitos were held in check; and the tide of barbarism, which had threatened to submerge the empire on this side, was effectually resisted and rolled back.

With Rome Chosroes maintained for eleven years the most friendly and cordial relations. Whatever humiliation he may have felt when he accepted the terms on which alone Maurice was willing to render him aid, having once agreed to them, he stifled all regrets, made no attempt to evade his obligations, abstained from every endeavor to undo by intrigue what he had done, unwillingly indeed, but yet with his eyes open. Once only during the eleven years did a momentary cloud arise between him and his benefactor. In the year A.D. 600 some of the Saracenic tribes dependent on Rome made an incursion across the Euphrates into Persian territory, ravaged it far and wide, and returned with their booty into the desert. Chosroes was justly offended, and might fairly have considered that a casus belli had arisen; but he allowed himself to be pacified by the representations of Maurice's envoy, George, and consented not to break the peace on account of so small a matter. George claimed the concession as a tribute to his own amiable qualities; but it is probable that the Persian monarch acted rather on the grounds of general policy than from any personal predilection.

Two years later the virtuous but perhaps over-rigid Maurice was deposed and murdered by the centurion, Phocas, who, on the strength of his popularity with the army, boldly usurped the throne. Chosroes heard with indignation of the execution of his ally and friend, of the insults offered to his remains, and of the assassination of his numerous sons, and of his brother. One son, he heard, had been sent off by Maurice to implore aid from the Persians; he had been overtaken and put to death by the emissaries of the usurper; but rumor, always busy where royal personages are concerned, asserted that he lived, that he had escaped his pursuers, and had reached Ctesiphon. Chosroes was too much interested in the acceptance of the rumor to deny it; he gave out that Theodosius was at his court, and notified that it was his intention to assert his right to the succession. When, five months after his coronation, Phocas sent an envoy to announce his occupation of the throne, and selected the actual murderer of Maurice to fill the post, Chosroes determined on an open rupture. He seized Lilius, the envoy, threw him into prison, announced his intention of avenging his deceased benefactor, and openly declared war against Rome.

The war burst out the next year (A.D. 603). On the Roman side there was disagreement, and even civil war; for Narses, who had held high command in the East ever since he restored Chosroes to the throne of his ancestors, on hearing of the death of Maurice, took up arms against Phocas, and, throwing himself into Edessa, defied the forces of the usurper. Germanus, who commanded at Daras, was a general of small capacity, and found himself quite unable to make head, either against Narses in Edessa, or against Chosroes, who led his troops in person into Mesopotamia. Defeated by Chosroes in a battle near Daras, in which he received a mortal wound, Germanus withdrew to Constantia, where he died eleven days afterwards. A certain Leontius, a eunuch, took his place, but was equally unsuccessful. Chosroes defeated him at Arxamus, and took a great portion of his army prisoners; whereupon he was recalled by Phocas, and a third leader, Domentziolus, a nephew of the emperor, was appointed to the command. Against him the Persian monarch thought it enough to employ generals. The war now languished for a short space; but in A.D. 605 Chosroes came up in person against Daras, the great Roman stronghold in these parts, and besieged it for the space of nine months, at the end of which time it surrendered. The loss was a severe blow to the Roman prestige, and was followed in the next year by a long series of calamities. Chosroes took Tur-abdin, Hesen-Cephas, Mardin, Capher-tuta, and Amida. Two years afterwards, A.D. 607, he captured Harran (Carrhse), Ras-el-ain (Resaina), and Edessa, the capital of Osrhoene, after which he pressed forward to the Euphrates, crossed with his army into Syria, and fell with fury on the Roman cities west of the river. Mabog or Hierapolis, Kenneserin, and Berhoea (now Aleppo), were invested and taken in the course of one or at most two campaigns; while at the same time (A.D. 609) a second Persian army, under a general whose name is unknown, after operating in Armenia, and taking Satala and Theodosiopolis, invaded Cappadocia and threatened the great city of Caesarea Mazaca, which was the chief Roman stronghold in these parts. Bands of marauders wasted the open country, carrying terror through the fertile districts of Phyrgia and Galatia, which had known nothing of the horrors of war for centuries, and were rich with the accumulated products of industry. According to Theophanes, some of the ravages even penetrated as far as Chalcedon, on the opposite side of the straits from Constantinople; but this is probably the anticipation of an event belonging to a later time. No movements of importance are assigned to A.D. 610; but in the May of the next year the Persians once more crossed the Euphrates, completely defeated and destroyed the Roman army which protected Syria, and sacked the two great cities of Apameia and Antioch.

Meantime a change had occurred at Constantinople. The double revolt of Heraclius, prefect of Egypt, and Gregory, his lieutenant, had brought the reign of the brutal and incapable Phocas to an end, and placed upon the imperial throne a youth of promise, innocent of the blood of Maurice, and well inclined to avenge it. Chosroes had to consider whether he should adhere to his original statement, that he took up arms to punish the murderer of his friend, and benefactor, and consequently desist from further hostilities now that Phocas was dead, or whether, throwing consistency to the winds, he should continue to prosecute the war, notwithstanding the change of rulers, and endeavor to push to the utmost the advantage which he had already obtained. He resolved on this latter alternative. It was while the young Heraclius was still insecure in his seat that he sent his armies into Syria, defeated the Roman troops, and took Antioch and Apameia. Following up blow with blow, he the next year (A.D. 612) invaded Cappadocia a second time and captured Csesarea Mazaca. Two years later (A.D. 614) he sent his general Shahr-Barz, into the region east of the Antilibanus, and took the ancient and famous city of Damascus. From Damascus, in the ensuing year, Shahr-Barz advanced against Palestine, and, summoning the Jews to his aid, proclaimed a Holy War against the Christian misbelievers, whom he threatened to enslave or exterminate. Twenty-six thousand of these fanatics flocked to his standard; and having occupied the Jordan region and Galileee, Shahr-Barz in A.D. 615 invested Jerusalem, and after a siege of eighteen days forced his way into the town, and gave it over to plunder and rapine. The cruel hostility of the Jews had free vent. The churches of Helena, of Constantine, of the Holy Sepulchre, of the Resurrection, and many others, were burnt or ruined; the greater part of the city was destroyed; the sacred treasuries were plundered; the relics scattered or carried off; and a massacre of the inhabitants, in which the Jews took the chief part, raged throughout the whole city for some days. As many as seventeen thousand or, according to another account, ninety thousand, were slain. Thirty-five thousand were made prisoners. Among them was the aged Patriarch, Zacharius, who was carried captive into Persia, where he remained till his death.

The Cross found by Helena, and believed to be "the True Cross," was at the same time transported to Ctesiphon, where it was preserved with care and duly venerated by the Christian wife of Chosroes.

A still more important success followed. In A.D. 616 Shahr-Barz proceeded from Palestine into Egypt, which had enjoyed a respite from foreign war since the time of Julius Caesar, surprised Pelusium, the key of the country, and, pressing forward across the Delta, easily made himself master of the rich and prosperous Alexandria. John the Merciful, who was the Patriarch, and Nicetas the Patrician, who was the governor, had quitted the city before his arrival, and had fled to Cyprus. Hence scarcely any resistance was made. The fall of Alexandria was followed at once by the complete submission of the rest of Egypt. Bands of Persians advanced up the Nile valley to the very confines of Ethiopia, and established the authority of Chosroes over the whole country—a country in which no Persian had set foot since it was wrested by Alexander of Macedon from Darius Codomannus.

While this remarkable conquest was made in the southwest, in the north-west another Persian army under another general, Saina or Shahen, starting from Cappadocia, marched through Asia Minor to the shores of the Thracian Bosphorus, and laid siege to the strong city of Chalcedon, which lay upon the strait, just opposite Constantinople. Chalcedon made a vigorous resistance; and Heraclius, anxious to save it, had an interview with Shahen, and at his suggestion sent three of his highest nobles as ambassadors to Chosroes, with a humble request for peace. The overture was ineffectual. Chosroes imprisoned the ambassadors and entreated them cruelly; threatened Shahen with death for not bringing Heraclius in chains to the foot of his throne; and declared in reply that he would grant no terms of peace—the empire was his, and Heraclius must descend from his throne. Soon afterwards (A.D. 617) Chalcedon, which was besieged through the winter, fell; and the Persians established themselves in this important stronghold, within a mile of Constantinople. Three years afterwards, Ancyra (Angora), which had hitherto resisted the Persian arms, was taken; and Rhodes, though inaccessible to an enemy who was without a naval force, submitted.

Thus the whole of the Roman possessions in Asia and Eastern Africa were lost in the space of fifteen years. The empire of Persia was extended from the Tigris and Euphrates to the Egean and the Nile, attaining once more almost the same dimensions that it had reached under the first and had kept until the third Darius. It is difficult to say how far their newly acquired provinces wore really subdued, organized, and governed from Ctesiphon, how far they were merely overrun, plundered, and then left to themselves. On the one hand, we have indications of the existence of terrible disorders and of something approaching to anarchy in parts of the conquered territory during the time that it was held by the Persians; on the other, we seem to see an intention to retain, to govern, and even to beautify it. Eutychius relates that, on the withdrawal of the Romans from Syria, the Jews resident in Tyre, who numbered four thousand, plotted with their co-religionists of Jerusalem, Cyprus, Damascus, and Galilee, a general massacre of the Tyrian Christians on a certain day. The plot was discovered; and the Jews of Tyre were arrested and imprisoned by their fellow-citizens, who put the city in a state of defence; and when the foreign Jews, to the number of 26,000, came at the appointed time, repulsed them from the walls, and defeated them with great slaughter. This story suggests the idea of a complete and general disorganization. But on the other hand we hear of an augmentation of the revenue under Chosroes II., which seems to imply the establishment in the regions conquered of a settled government; and the palace at Mashita, discovered by a recent traveller, is a striking proof that no temporary occupation was contemplated, but that Chosroes regarded his conquests as permanent acquisitions, and meant to hold them and even visit them occasionally.

Heraclius was now well-nigh driven to despair. The loss of Egypt reduced Constantinople to want, and its noisy populace clamored for food. The Avars overran Thrace, and continually approached nearer to the capital. The glitter of the Persian arms was to be seen at any moment, if he looked from his palace windows across the Bosphorus. No prospect of assistance or relief appeared from any quarter. The empire was reduced to the walls of Constantinople, with the remnant of Greece, Italy, and Africa, and some maritime cities, from Tyre to Trebizond, of the Asiatic Coast. It is not surprising that under the circumstances the despondent monarch determined on flight, and secretly made arrangements for transporting himself and his treasures to the distant Carthage, where he might hope at least to find himself in safety. His ships, laden with their precious freight, had put to sea, and he was about to follow them, when his intention became known or was suspected; the people rose; and the Patriarch, espousing their side, forced the reluctant prince to accompany him to the church of St. Sophia, and there make oath that, come what might, he would not separate his fortunes from those of the imperial city.

Baffled in his design to escape from his difficulties by flight, Heraclius took a desperate resolution. He would leave Constantinople to its fate, trust its safety to the protection afforded by its walls and by the strait which separated it from Asia, embark with such troops as he could collect, and carry the war into the enemy's country. The one advantage which he had over his adversary was his possession of an ample navy, and consequent command of the sea and power to strike his blows unexpectedly in different quarters. On making known his intention, it was not opposed, either by the people or by the Patriarch. He was allowed to coin the treasures of the various churches into money, to collect stores, enroll troops, and, on the Easter Monday of A.D. 622, to set forth on his expedition.

His fleet was steered southward, and, though forced to contend with adverse gales, made a speedy and successful voyage through the Propontis, the Hellespont, the Egean, and the Cilician Strait, to the Gulf of Issus, in the angle between Asia Minor and Syria. The position was well chosen, as one where attack was difficult, where numbers would give little advantage, and where consequently a small but resolute force might easily maintain itself against a greatly superior enemy. At the same time it was a post from which an advance might conveniently be made in several directions, and which menaced almost equally Asia Minor, Syria, and Armenia. Moreover, the level tract between the mountains and the sea was broad enough for the manoeuvres of such an army as Heraclius commanded, and allowed him to train his soldiers by exercises and sham fights to a familiarity with the sights and sounds and movements of a battle. He conjectured, rightly enough, that he would not long be left unmolested by the enemy. Shahr-Barz, the conqueror of Jerusalem and Egypt, was very soon sent against him; and, after various movements, which it is impossible to follow, a battle was fought between the two armies in the mountain country towards the Armenian frontier, in which the hero of a hundred fights was defeated and the Romans, for the first time since the death of Maurice, obtained a victory. After this, on the approach of winter, Heraclius, accompanied probably by a portion of his army, returned by sea to Constantinople.

The next year the attack was made in a different quarter. Having concluded alliances with the Khan of the Khazars and some other chiefs of inferior power, Heraclius in the month of March embarked with 5000 men, and proceeded from Constantinople by way of the Black Sea first to Trebizond, and then to Mingrelia or Lazica. There he obtained contingents from his allies, which, added to the forces collected from. Trebizond and the other maritime towns, may perhaps have raised his troops to the number of 120,000, at which we find them estimated. With this army, he crossed the Araxes, and invaded Armenia. Chosroes, on receiving the intelligence, proceeded into Azorbijan with 40,000 men, and occupied the strong city of Canzaca, the site of which is probably marked by the ruins known as Takht-i-Suleiman. At the same time he ordered two other armies, which he had sent on in advance, one of them commanded by Shahr-Barz, the other by Shahen, to effect a junction and oppose themselves to the further progress of the emperor. The two generals were, however, tardy in their movements, or at any rate were outstripped by the activity of Heraclius, who, pressing forward from Armenia into Azerbijan, directed his march upon Canzaca, hoping to bring the Great King to a battle. His advance-guard of Saracens did actually surprise the picquets of Chosroes; but the king himself hastily evacuated the Median stronghold, and retreated southwards through Ardelan towards the Zagros mountains, thus avoiding the engagement which was desired by his antagonist. The army, on witnessing the flight of their monarch, broke up and dispersed. Heraclius pressed upon the flying host and slew all whom he caught, but did not suffer himself to be diverted from his main object, which was to overtake Chosroes. His pursuit, however, was unsuccessful. Chosroes availed himself of the rough and difficult country which lies between Azerbijan and the Mesopotamian lowland, and by moving from, place to place contrive to baffle his enemy. Winter arrived, and Heraclius had to determine whether he would continue his quest at the risk of having to pass the cold season in the enemy's country, far from all his resources, or relinquish it and retreat to a safe position. Finding his soldiers divided in their wishes, he trusted the decision to chance, and opening the Gospel at random settled the doubt by applying the first passage that met his eye to its solution. The passage suggested retreat; and Heraclius, retracing his steps, recrossed the Araxes, and wintered in Albania.

The return of Heraclius was not unmolested. He had excited the fanaticism of the Persians by destroying, wherever he went, the temples of the Magians, and extinguishing the sacred fire, which it was a part of their religion to keep continually burning. He had also everywhere delivered the cities and villages to the flames, and carried off many thousands of the population. The exasperated enemy consequently hung upon his rear, impeded his march, and no doubt caused him considerable loss, though, when it came to fighting, Heraclius always gained the victory. He reached Albania without sustaining any serious disaster, and even brought with him 50,000 captives; but motives of pity, or of self-interest, caused him soon afterwards to set these prisoners free. It would have been difficult to feed and house them through the long and severe winter, and disgraceful to sell or massacre them.

In the year A.D. 624 Chosroes took the offensive, and, before Heraclius had quitted his winter quarters, sent a general, at the head of a force of picked troops, into Albania, with the view of detaining him in that remote province during the season of military operations. But Sarablagas feared his adversary too much to be able very effectually to check his movements; he was content to guard the passes, and hold the high ground, without hazarding an engagement. Heraclius contrived after a time to avoid him, and penetrated into Persia through a series of plains, probably those along the course and about the mouth of the Araxes. It was now his wish to push rapidly southward; but the auxiliaries on whom he greatly depended were unwilling; and, while he doubted what course to take, three Persian armies, under commanders of note, closed in upon him, and threatened his small force with destruction. Heraclius feigned a disordered flight, and drew on him an attack from two out of the three chiefs, which he easily repelled. Then he fell upon the third, Shahen, and completely defeated him. A way seemed to be thus opened for him into the heart of Persia, and he once more set off to seek Chosroes; but now his allies began to desert his standard, and return to their homes; the defeated Persians rallied and impeded his march; he was obliged to content himself with a third, victory, at a place which Theophanes calls Salban, where he surprised Shahr-Barz in the dead of the night, massacred his troops, his wives, his officers, and the mass of the population, which fought from the flat roofs of the houses, took the general's arms and equipage, and was within a little of capturing Shahr-barz himself. The remnant of the Persian army fled in disorder, and was hunted down by Heraclius, who pursued the fugitives unceasingly till the cold season approached, and he had to retire into cantonments. The half-burnt Salban afforded a welcome shelter to his troops during the snows and storms of an Armenian winter.

Early in the ensuing spring the indefatigable emperor again set his troops in motion, and, passing the lofty range which separates the basin of Lake Van from the streams that flow into the upper Tigris, struck that river, or rather its large affluent, the Bitlis Chai, in seven days from Salban, crossed into Arzanene, and proceeding westward recovered Martyropolis and Amida, which had now been in the possession of the Persians for twenty years. At Amida he made a halt, and wrote to inform the Senate of Constantinople of his position and his victories, intelligence which they must have received gladly after having lost sight of him for above a twelvemonth. But he was not allowed to remain long undisturbed. Before the end of March Shahr-Barz had again taken the field in force, had occupied the usual passage of the Euphrates, and threatened the line of retreat which Heraclius had looked upon as open to him. Unable to cross the Euphrates by the bridge, which Shahr-barz had broken, the emperor descended the stream till he found a ford, when he transported his army to the other bank, and hastened by way of Samosata and Germanicaea into Cilicia. Here he was once more in his own territory, with the sea close at hand, ready to bring him supplies or afford him a safe retreat, in a position with whose advantages he was familiar, where broad plains gave an opportunity for skilful maneuvers, and deep rapid rivers rendered defence easy. Heraclius took up a position on the right bank of the Sarus (Syhuri), in the immediate vicinity of the fortified bridge by which alone the stream could be crossed. Shahr-Barz followed, and ranged his troops along the left bank, placing the archers in the front line, while he made preparations to draw the enemy from the defence of the bridge into the plain on the other side. He was so far successful that the Roman occupation of the bridge was endangered; but Heraclius, by his personal valor and by almost superhuman exertions, restored the day; with his own hand he struck down a Persian of gigantic stature and flung him from the bridge into the river; then pushing on with a few companions, he charged the Persian host in the plain, receiving undaunted a shower of blows, while he dealt destruction on all sides. The fight was prolonged until the evening and even then was undecided; but Shahr-Barz had convinced himself that he could not renew the combat with any prospect of victory. He therefore retreated during the night, and withdrew from Cilicia. Heraclius, finding himself free to march where he pleased, crossed the Taurus, and proceeded to Sebaste (Sivas), upon the Halys, where he wintered in the heart of Cappadocia, about half-way between the two seas. According to Theophanes the Persian monarch was so much enraged at this bold and adventurous march, and at the success which had attended it, that, by way of revenging himself on Heraclius, he seized the treasures of all the Christian churches in his dominions, and compelled the orthodox believers to embrace the Nestorian heresy. The twenty-fourth year of the war had now arrived, and it was difficult to say on which side lay the balance of advantage. If Chosroes still maintained his hold on Syria, Egypt, and Asia Minor as far as Chalcedon, if his troops still flaunted their banners within sight of Constantinople, yet on the other hand he had seen his hereditary dominions deeply penetrated by the armies of his adversary; he had had his best generals defeated, his cities and palaces burnt, his favorite provinces wasted; Heraclius had proved himself a most formidable opponent; and unless some vital blow could be dealt him at home, there was no forecasting the damage that he might not inflict on Persia by a fresh invasion. Chosroes therefore made a desperate attempt to bring the war to a close by an effort, the success of which would have changed the history of the world. Having enrolled as soldiers, besides Persians, a vast number of foreigners and slaves, and having concluded a close alliance with the Khan of the Avars, he formed two great armies, one of which was intended to watch Heraclius in Asia Minor, while the other co-operated with the Avars and forced Constantinople to surrender. The army destined to contend with the emperor was placed under the command of Shahen; that which was to bear a part in the siege of Constantinople was committed to Shahr-Barz. It is remarkable that Heraclius, though quite aware of his adversary's plans, instead of seeking to baffle them, made such arrangements as facilitated the attempt to put them into execution. He divided his own troops into three bodies, one only of which he sent to aid in the defence of his capital. The second body he left with his brother Theodore, whom he regarded as a sufficient match for Shahen. With the third division he proceeded eastward to the remote province of Lazica, and there engaged in operations which could but very slightly affect the general course of the war. The Khazars were once more called in as allies; and their Khan, Ziebel, who coveted the plunder of Tiflis, held an interview with the emperor in the sight of the Persians who guarded that town, adored his majesty, and received from his hands the diadem that adorned his own brow. Richly entertained, and presented with all the plate used in the banquet, with a royal robe, and a pair of pearl earrings, promised moreover the daughter of the emperor (whose portrait he was shown) in marriage, the barbarian chief, dazzled and flattered, readily concluded an alliance, and associated his arms with those of the Romans. A joint attack was made upon Tiflis, and the town was reduced to extremities; when Sarablagas, with a thousand men, contrived to throw himself into it, and the allies, disheartened thereby, raised the siege and retired.

Meanwhile, in Asia Minor, Theodore engaged the army of Shahen; and, a violent hailstorm raging at the time, which drove into the enemy's face, while the Romans were, comparatively speaking, sheltered from its force, he succeeded in defeating his antagonist with great slaughter. Chosroes was infuriated; and the displeasure of his sovereign weighed so heavily upon the mind of Shahen that he shortly afterwards sickened and died. The barbarous monarch gave orders that his corpse should be embalmed and sent to the court, in order that he might gratify his spleen by treating it with the grossest indignity.

At Constantinople the Persian cause was equally unsuccessful. Shahr-Barz, from Chalcedon, entered into negotiations with the Khan of the Avars, and found but little difficulty in persuading him to make an attempt upon the imperial city. From their seats beyond the Danube a host of barbarians—Avars, Slaves, Gepidas, Bulgarians, and others—advanced through the passes of Heemus into the plains of Thrace, destroying and ravaging. The population fled before them and sought the protection of the city walls, which had been carefully strengthened in expectation of the attack, and were in good order. The hordes forced the outer works; but all their efforts, though made both by land and sea, were unavailing against the main defences; their attempt to sap the wall failed; their artillery was met and crushed by engines of greater power; a fleet of Slavonian canoes, which endeavored to force an entrance by the Golden Horn, was destroyed or driven ashore; the towers with which they sought to overtop the walls were burnt; and, after ten days of constantly repeated assaults, the barbarian leader became convinced that he had undertaken an impossible enterprise, and, having burnt his engines and his siege works, he retired. The result might have been different had the Persians, who were experienced in the attack of walled places, been able to co-operate with him; but the narrow channel which flowed between Chalcedon and the Golden Horn proved an insurmountable barrier; the Persians had no ships, and the canoes of the Slavonians were quite unable to contend with the powerful galleys of the Byzantines, so that the transport of a body of Persian troops from Asia to Europe by their aid proved impracticable. Shahr-Barz had the annoyance of witnessing the efforts and defeat of his allies, without having it in his power to take any active steps towards assisting the one or hindering the other.

The war now approached its termination; for the last hope of the Persians had failed; and Heraclius, with his mind set at rest as regarded his capital, was free to strike at any part of Persia that he pleased, and, having the prestige of victory and the assistance of the Khazars, was likely to carry all before him. It is not clear how he employed himself during the spring and summer of A.D. 627; but in the September of that year he started from Lazica with a large Roman army and a contingent of 40,000 Khazar horse, resolved to surprise his adversary by a winter campaign, and hoping to take him at a disadvantage. Passing rapidly through Armenia and Azerbijan without meeting an enemy that dared to dispute his advance, suffering no loss except from the guerilla warfare of some bold spirits among the mountaineers of those regions, he resolved, notwithstanding the defection of the Khazars, who declined to accompany him further south than Azerbijan, that he would cross the Zagros mountains into Assyria, and make a dash at the royal cities of the Mesopotamian region, thus retaliating upon Chosroes for the Avar attack upon Constantinople of the preceding year, undertaken at his instigation. Chosroes himself had for the last twenty-four years fixed his court at Dastagherd in the plain country, about seventy miles to the north of Ctesiphon. It seemed to Heraclius that this position might perhaps be reached, and an effective blow struck against the Persian power. He hastened, therefore, to cross the mountains; and the 9th of October saw him at Chnaethas, in the low country, not far from Arbela, where he refreshed his army by a week's rest. He might now easily have advanced along the great post-road which connected Arbela with Dastagherd and Ctesiphon; but he had probably by this time received information of the movements of the Persians, and was aware that by so doing he would place himself between two fires, and run the chance of being intercepted in his retreat. For Chosroes, having collected a large force, had sent it, under Ehazates, a new general, into Azerbijan; and this force, having reached Canzaca, found itself in the rear of Heraclius, between him and Lazica. Heraclius appears not to have thought it safe to leave this enemy behind him, and therefore he idled away above a month in the Zab region, waiting for Ehazates to make his appearance. That general had strict orders from the Great King to fight the Romans wherever he found them, whatever might be the consequence; and he therefore followed, as quickly as he could, upon Heraclius's footsteps, and early in December came up with him in the neighborhood of Nineveh. Both parties were anxious for an immediate engagement, Rhazates to carry out his master's orders, Heraclius because he had heard that his adversary would soon receive a reinforcement. The battle took place on the 12th of December, in the open plain to the north of Nineveh. It was contested from early dawn to the eleventh hour of the day, and was finally decided, more by the accident that Rhazates and the other Persian commanders were slain, than by any defeat of the soldiers. Heraclius is said to have distinguished himself personally during the fight by many valiant exploits; but he does not appear to have exhibited any remarkable strategy on the occasion. The Persians lost their generals, their chariots, and as many as twenty-eight standards; but they were not routed, nor driven from the field. They merely drew off to the distance of two bowshots, and there stood firm till after nightfall. During the night they fell back further upon their fortified camp, collected their baggage, and retired to a strong position at the foot of the mountains. Here they were joined by the reinforcement which Chosroes had sent to their aid; and thus strengthened they ventured to approach Heraclius once more, to hang on his rear, and impede his movements. He, after his victory, had resumed his march southward, had occupied Nineveh, recrossed the Groat Zab, advanced rapidly through Adiabene to the Lesser Zab, seized its bridges by a forced march of forty-eight (Roman) miles, and conveyed his army safely to its left bank, where he pitched his camp at a place called Yesdem, and once more allowed his soldiers a brief repose for the purpose of keeping Christmas. Chosroes had by this time heard of the defeat and death of Rhazates, and was in a state of extreme alarm. Hastily recalling Shahr-Barz from Chalcedon, and ordering the troops lately commanded by Rhazates to outstrip the Romans, if possible, and interpose themselves between Heraclius and Dastaghord, he took up a strong position near that place with his own army and a number of elephants, and expressed an intention of there awaiting his antagonist. A broad and deep river, or rather canal, known as the Baras-roth or Barazrud, protected his front; while at some distance further in advance was the Torna, probably another canal, where he expected that the army of Rhazates would make a stand. But that force, demoralized by its recent defeat, fell back from the line of the Torna, without even destroying the bridge over it; and Chosroes, finding the foe advancing on him, lost heart, and secretly fled from Dastagherd to Ctesiphon, whence he crossed the Tigris to Guedeseer or Seleucia, with his treasure and the best-loved of his wives and children. The army lately under Rhazates rallied upon the line of the Nahr-wan canal, three miles from Ctesiphon; and here it was largely reinforced, though with a mere worthless mob of slaves and domestics. It made however a formidable show, supported by its elephants, which numbered two hundred; it had a deep and wide cutting in its front; and, this time, it had taken care to destroy all the bridges by which the cutting might have been crossed. Heraclius, having plundered the rich palace of Dastagherd, together with several less splendid royal residences, and having on the 10th of January encamped within twelve miles of the Nahrwan, and learnt from the commander of the Armenian contingent, whom he sent forward to reconnoitre, that the canal was impassable, came to the conclusion that his expedition had reached its extreme limit, and that prudence required him to commence his retreat. The season had been, it would seem, exceptionally mild, and the passes of the mountains were still open; but it was to be expected that in a few weeks they would be closed by the snow, which always falls heavily during some portion of the winter. Heraclius, therefore, like Julian, having come within sight of Ctesiphon, shrank from the idea of besieging it, and, content with the punishment that he had inflicted on his enemy by wasting and devastation, desisted from his expedition, and retraced his steps. In his retreat he was more fortunate than his great predecessor. The defeat which he had inflicted on the main army of the Persians paralyzed their energies, and it would seem that his return march was unmolested. He reached Siazurus (Shehrizur) early in February, Barzan (Berozeh) probably on the 1st of March,176 and on the 11th of March Canzaca, where he remained during the rest of the winter.

Chosroes had escaped a great danger, but he had incurred a terrible disgrace. He had fled before his adversary without venturing to give him battle. He had seen palace after palace destroyed, and had lost the magnificent residence where he had held his court for the last four-and-twenty years. The Romans had recovered 300 standards, trophies gained in the numerous victories of his early years. They had shown themselves able to penetrate into the heart of his empire, and to retire without suffering any loss. Still, had he possessed a moderate amount of prudence, Chosroes might even now have surmounted the perils of his position, and have terminated his reign in tranquillity, if not in glory. Heraclius was anxious for peace, and willing to grant it on reasonable conditions. He did not aim at conquests, and would have been contented at any time with the restoration of Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor. The Persians generally were weary of the war, and would have hailed with joy almost any terms of accommodation. But Chosroes was obstinate; he did not know how to bear the frowns of fortune; the disasters of the late campaign, instead of bending his spirit, had simply exasperated him, and he vented upon his own subjects the ill-humor which the successes of his enemies had provoked. Lending a too ready ear to a whispered slander, he ordered the execution of Shahr-Barz, and thus mortally offended that general, to whom the despatch was communicated by the Romans. He imprisoned the officers who had been defeated by, or had fled before Heraclius. Several other tyrannical acts are alleged against him; and it is said that he was contemplating the setting aside of his legitimate successor, Siroes, in favor of a younger son, Merdasas, his offspring by his favorite wife, the Christian Shirin, when a rebellion broke out against his authority. Gurdanaspa, who was in command of the Persian troops at Ctesiphon, and twenty-two nobles of importance, including two sons of Shahr-Barz, embraced the cause of Siroes, and seizing Chosroes, who meditated flight, committed him to "the House of Darkness," a strong place where he kept his money. Here he was confined for four days, his jailers allowing him daily a morsel of bread and a small quantity of water; when he complained of hunger, they told him, by his son's orders, that he was welcome to satisfy his appetite by feasting upon his treasures. The officers whom he had confined were allowed free access to his prison, where they insulted him and spat upon him. Merdasas, the son whom he preferred, and several of his other children, were brought into his presence and put to death before his eyes. After suffering in this way for four days he was at last, on the fifth day from his arrest (February 28), put to death in some cruel fashion, perhaps, like St. Sebastian, by being transfixed with arrows. Thus perished miserably the second Chosroes, after having reigned thirty-seven years (A.D. 591-628), a just but tardy Nemesis overtaking the parricide.

The Oriental writers represent the second Chosroes as a monarch whose character was originally admirable, but whose good disposition was gradually corrupted by the possession of sovereign power. "Parviz," says Mirkhond, "holds a distinguished rank among the kings of Persia through the majesty and firmness of his government, the wisdom of his views, and his intrepidity in carrying them out, the size of his army, the amount of his treasure, the flourishing condition of the provinces during his reign, the security of the highways, the prompt and exact obedience which he enforced, and his unalterable adherence to the plans which he once formed." It is impossible that these praises can have been altogether undeserved; and we are bound to assign to this monarch, on the authority of the Orientals, a vigor of administration, a strength of will, and a capacity for governing, not very commonly possessed by princes born in the purple. To these merits we may add a certain grandeur of soul, and power of appreciating the beautiful and the magnificent, which, though not uncommon in the East, did not characterize many of the Sassanian sovereigns. The architectural remains of Chosroes, which will be noticed in a future chapter, the descriptions which have come down to us of his palaces at Dastagherd and Canzaca, the accounts which we have of his treasures, his court, his seraglio, even his seals, transcend all that is known of any other monarch of his line. The employment of Byzantine sculptors and architects, which his works are thought to indicate, implies an appreciation of artistic excellence very rare among Orientals. But against these merits must be set a number of most serious moral defects, which may have been aggravated as time went on, but of which we see something more than the germ, even while he was still a youth. The murder of his father was perhaps a state necessity, and he may not have commanded it, or have been accessory to it before the fact; but his ingratitude towards his uncles, whom he deliberately put to death, is wholly unpardonable, and shows him to have been cruel, selfish, and utterly without natural affection, even in the earlier portion of his reign. In war he exhibited neither courage nor conduct; all his main military successes were due to his generals; and in his later years he seems never voluntarily to have exposed himself to danger. In suspecting his generals, and ill-using them while living, he only followed the traditions of his house; but the insults offered to the dead body of Shahen, whose only fault was that he had suffered a defeat, were unusual and outrageous. The accounts given of his seraglio imply either gross sensualism or extreme ostentation; perhaps we may be justified in inclining to the more lenient view, if we take into consideration the faithful attachment which he exhibited towards Shirin. The cruelties which disgraced his later years are wholly without excuse; but in the act which deprived him of his throne, and brought him to a miserable end—his preference of Merdasas as his successor—he exhibited no worse fault than an amiable weakness, a partiality towards the son of a wife who possessed, and seems to have deserved, his affection.

The coins of the second Chosroes are numerous in the extreme, and present several peculiarities. The ordinary type has, on the obverse, the king's head in profile, covered by a tiara, of which the chief ornament is a crescent and star between two outstretched wings. The head is surrounded by a double pearl bordering, outside of which, in the margin, are three crescents and stars. The legend is Khusrui afzud, with a monogram of doubtful meaning. The reverse shows the usual fire altar and supporters, in a rude form, enclosed by a triple pearl bordering. In the margin, outside the bordering, are four crescents and stars. The legend is merely the regnal year and a mint-mark. Thirty-four mint-marks have been ascribed to Chosroes II. [PLATE XXIII., Fig. 4.]

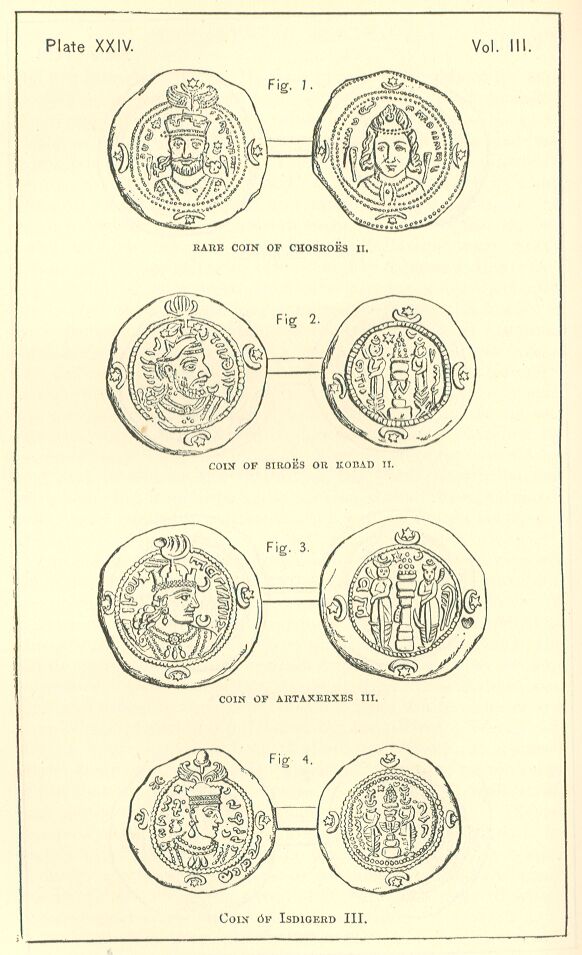

A rarer and more curious type of coin, belonging to this monarch, presents on the obverse the front face of the king, surmounted by a mural crown, having the star and crescent between outstretched wings at top. The legend is Khusrui mallean malka—afzud. "Chosroes, king of kings—increase (be his)." The reverse has a head like that of a woman, also fronting the spectator, and wearing a band enriched with pearls across the forehead, above which the hair gradually converges to a point. [PLATE XXIV., Fig. 1.] A head very similar to this is found on Indo-Sassanian coins. Otherwise we might have supposed that the uxorious monarch had wished to circulate among his subjects the portrait of his beloved Shirin.