Architecture of the Sassanians. Its Origin. Its Peculiarities. Oblong Square Plan. Arched Entrance Halls. Domes resting on Pendentives. Suites of Apartments. Ornamentation: Exterior, by Pilasters, Cornices, String-courses, and shallow arched Recesses, with Pilasters between them; Interior, by Pillars supporting Transverse Bibs,or by Door-ways and False Windows, like the Persopolitan. Specimen Palaces at Serbistan, at Firuzbad, at Ctesiphon, at Mashita. Elaborate Decoration at the last-named Palace. Decoration Elsewhere. Arch of Takht-i-Bostan. Sassanian Statuary. Sassanian Bas-reliefs. Estimate of their Artistic Value. Question of the Employment by the Sassanians of Byzantine Artists. General Summary.

"With the accession of the Sassanians, Persia regained much of that power and stability to which she had been so long a stranger.... The improvement in the fine arts at home indicates returning prosperity, and a degree of security unknown since the fall of the Achaemenidae."—Fergusson, History of Architecture, vol. i. pp. 381-3, 3d edition.

When Persia under the Sassanian princes shook off the barbarous yoke to which she had submitted for the space of almost five centuries, she found architecture and the other fine arts at almost the lowest possible ebb throughout the greater part of Western Asia. The ruins of the Achaemenian edifices, which were still to be seen at Pasargadae, Persopolis, and elsewhere, bore witness to the grandeur of idea, and magnificence of construction, which had once formed part of the heritage of the Persian nation; but the intervening period was one during which the arts had well-nigh wholly disappeared from the Western Asiatic world; and when the early sovereigns of the house of Sassan felt the desire, common with powerful monarchs, to exhibit their greatness in their buildings, they found themselves at the first without artists to design, without artisans to construct, and almost without models to copy. The Parthians, who had ruled over Persia for nearly four hundred years,' had preferred country to city life, tents to buildings, and had not themselves erected a single edifice of any pretension during the entire period of their dominion. Nor had the nations subjected to their sway, for the most part, exhibited any constructive genius, or been successful in supplying the artistic deficiencies of their rulers. In one place alone was there an exception to this general paralysis of the artistic powers. At Hatra, in the middle Mesopotamian region, an Arab dynasty, which held under the Parthian kings, had thought its dignity to require that it should be lodged in a palace, and had resuscitated a native architecture in Mesopotamia, after centuries of complete neglect. When the Sassanians looked about for a foundation on which they might work, and out of which they might form a style suitable to their needs and worthy of their power and opulence, they found what they sought in the Hatra edifice, which was within the limits of their kingdom, and at no great distance from one of the cities where they held their Court.

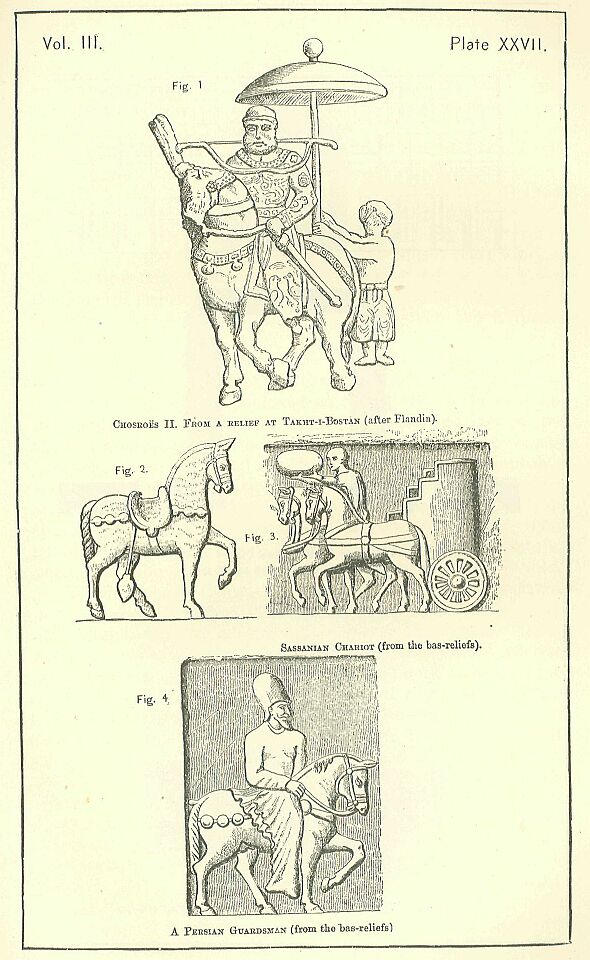

The early palaces of the Sassanians have ceased to exist. Artaxerxes, the son of Babek, Sapor the first, and their immediate successors, undoubtedly erected residences for themselves exceeding in size and richness the buildings which had contented the Parthians, as well as those in which their own ancestors, the tributary kings of Persia under Parthia, had passed their lives. But these residences have almost wholly disappeared. The most ancient of the Sassanian buildings which admit of being measured and described are assigned to the century between A.D. 350 and 450; and we are thus unable to trace the exact steps by which the Sassanian style was gradually elaborated. We come upon it when it is beyond the stage of infancy, when it has acquired a marked and decided character, when it no longer hesitates or falters, but knows what it wants, and goes straight to its ends. Its main features are simple, and are uniform from first to last, the later buildings being merely enlargements of the earlier, by an addition to the number or to the size of the apartments. The principal peculiarities of the style are, first, that the plan of the entire building is an oblong square, without adjuncts or projections; secondly, that the main entrance is into a lofty vaulted porch or hall by an archway of the entire width of the apartment; thirdly, that beside these oblong halls, the building contains square apartments, vaulted with domes, which are circular at their base, and elliptical in their section, and which rest on pendentives of an unusual character; fourthly, that the apartments are numerous and en suite, opening one into another, without the intervention of passages; and fifthly, that the palace comprises, as a matter of course, a court, placed towards the rear of the building, with apartments opening into it.

The oblong square is variously proportioned. The depth may be a little more than the breadth, or it may be nearly twice as much. In either case, the front occupies one of the shorter sides, or ends of the edifice. The outer wall is sometimes pierced by one entrance only; but, more commonly, entrances are multiplied beyond the limit commonly observed in modern buildings. The great entrance is in the exact centre of the front. This entrance, as already noticed, is commonly by a lofty arch which (if we set aside the domes) is of almost the full height of the building, and constitutes one of its most striking, and to Europeans most extraordinary, features. From the outer air, we look; as it were, straight into the heart of the edifice, in one instance to the depth of 115 feet, a distance equal to the length of Henry VII.'s Chapel at Westminster. The effect is very strange when first seen by the inexperienced traveller; but similar entrances are common in the mosques of Armenia and Persia, and in the palaces of the latter country. In the mosques "lofty and deeply-recessed portals," "unrivalled for grandeur and appropriateness," are rather the rule than the exception; and, in the palaces, "Throne-rooms" are commonly mere deep recesses of this character, vaulted or supported by pillars, and open at one end to the full width and height of the apartment. The height of the arch varies in Sassanian buildings from about fifty to eighty-five feet; it is generally plain, and without ornament; but in one case we meet with a foiling of small arches round the great one, which has an effect that is not unpleasing.

The domed apartments are squares of from twenty-five to forty feet, or a little more. The domes are circular at their base; but a section of them would exhibit a half ellipse, with its longest and shortest diameters proportioned as three to two. The height to which they rise from the ground is not much above seventy feet. A single building will have two or three domes, either of the same size, or occasionally of different dimensions. It is a peculiarity of their construction that they rest, not on drums, but on pendentives of a curious character. A series of semi-circular arches is thrown across the angles of the apartment, each projecting further into it than the preceding, and in this way the corners are got rid of, and the square converted into the circular shape. A cornice ran round the apartment, either above or below the pendentives, or sometimes both above and below. The domes were pierced by a number of small holes, which admitted some light, and the upper part of the walls between the pendentives was also pierced by windows.

There are no passages or corridors in the Sassanian palaces. The rooms for the most part open one into the other. Where this is not the case, they give upon a common meeting-ground, which is either an open court, or a large vaulted apartment. The openings are in general doorways of moderate size, but sometimes they are arches of the full width of the subordinate room or apartment. As many as seventeen or eighteen rooms have been found in a palace.

There is no appearance in any Sassanian edifice of a real second story. The famous Takht-i-Khosru presents externally the semblance of such an arrangement; but this seems to have been a mere feature of the external ornamentation, and to have had nothing to do with the interior.

The exterior ornamentation of the Sassanian buildings was by pilasters, by arched recesses, by cornices, and sometimes by string-courses. An ornamentation at once simple and elegant is that of the lateral faces of the palace at Firuzabad, where long reed-like pilasters are carried from the ground to the cornice, while between them are a series of tall narrow doubly recessed arches. Far less satisfactory is the much more elaborate design adopted at Ctesiphon, where six series of blind arches of different kinds are superimposed the one on the other, with string-courses between them, and with pilasters, placed singly or in pairs, separating the arches into groups, and not regularly superimposed, as pillars, whether real or seeming, ought to be.

The interior ornamentation was probably, in a great measure, by stucco, painting, and perhaps gilding. All this, however, if it existed, has disappeared; and the interiors now present a bare and naked appearance, which is only slightly relieved by the occasional occurrence of windows, of ornamental doorways, and of niches, which recall well-known features at Persepolis. In some instances, however, the arrangement of the larger rooms was improved by means of short pillars, placed at some distance from the walls, and supporting a sort of transverse rib, which broke the uniformity of the roof. The pillars were connected with the side walls by low arches.

Such are the main peculiarities of Sassanian palace architecture. The general effect of the great halls is grand, though scarcely beautiful; and, in the best specimens, the entire palace has an air of simple severity which is striking and dignified. The internal arrangements do not appear to be very convenient. Too much is sacrificed to regularity; and the opening of each room into its neighbor must, one would think, have been unsatisfactory. Still, the edifices are regarded as "indicating considerable originality and power," though they "point to a state of society when attention to security hardly allowed the architect the free exercise of the more delicate ornaments of his art."

From this general account of the main features of the architecture it is proposed now to proceed to a more particular description of the principal extant Sassanian buildings—the palaces at Serbistan, Firuzabad, Ctesiphon, and Mashita.

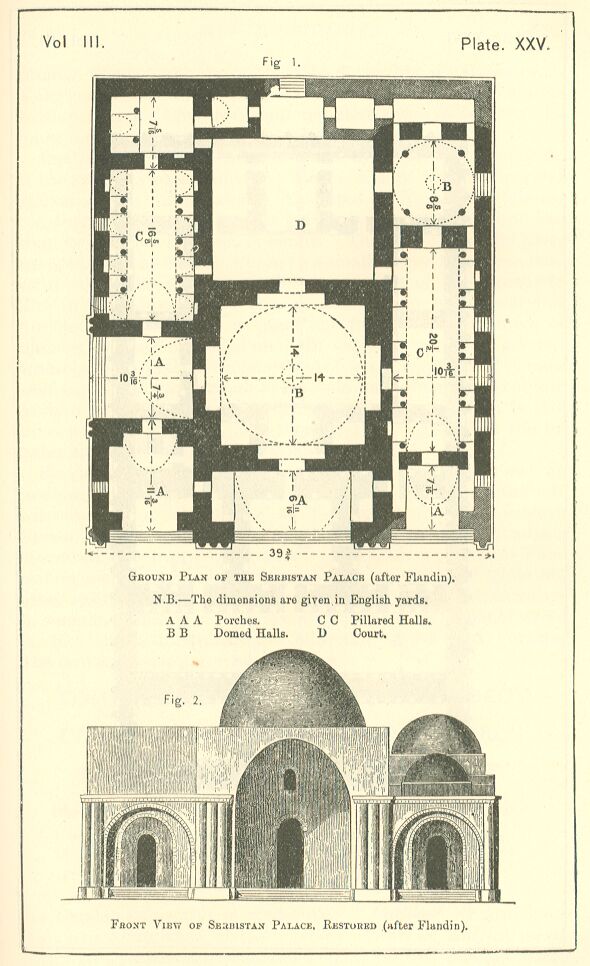

The palace at Serbistan is the smallest, and probably the earliest of the four. It has been assigned conjecturally to the middle of the fourth century, or the reign of Sapor II. The ground plan is an oblong but little removed from a square, the length being 42 French metres, and the breadth nearly 37 metres. [PLATE XXV., Fig. 1.] The building faces west, and is entered by three archways, between which are groups of three semi-circular pilasters, while beyond the two outer arches towards the angles of the building is a single similar pilaster. Within the archways are halls or porches of different depths, the central one of the three being the shallowest. [PLATE XXV., Fig. 2.] This opens by an arched doorway into a square chamber, the largest in the edifice. It is domed, and has a diameter of about 42 feet or, including recesses, of above 57 feet. The interior height of the dome from the floor is 65 feet. Beyond the domed chamber is a court, which measures 45 feet by 40, and has rooms of various sizes opening into it. One of these is domed; and others are for the most part vaulted. The great domed chamber opens towards the north, on a deep porch or hall, which was entered from without by the usual arched portal. On the south it communicates with a pillared hall, above 60 feet long by 30 broad. There is another somewhat similar hall on the north side of the building, in width about equal, but in length not quite 50 feet. In both halls the pillars are short, not exceeding six feet. They support piers, which run up perpendicularly for a considerable height, and then become ribs of the vaulting.

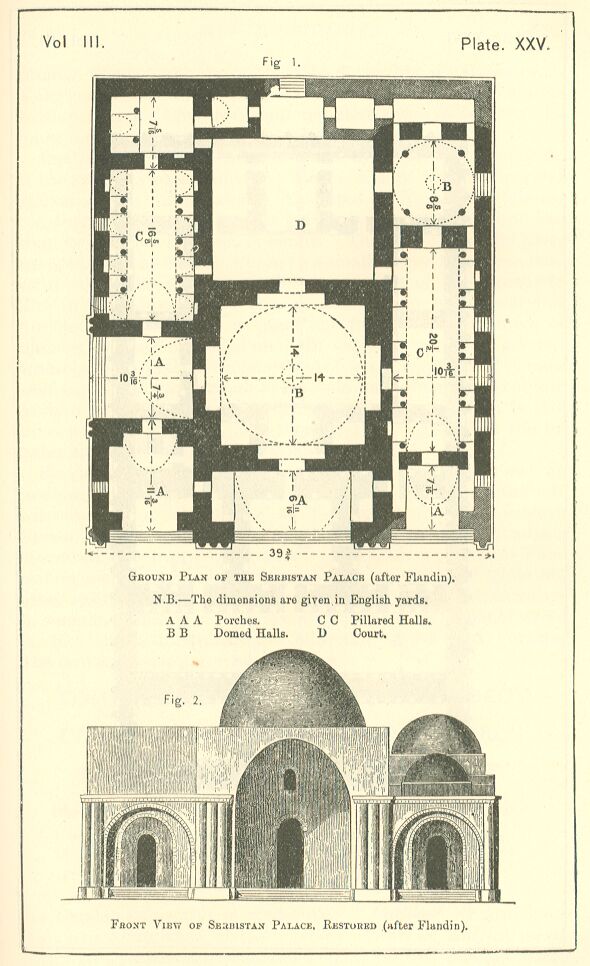

The Firuzabad palace has a length of above 390 and a width of above 180 feet. Its supposed date is A.D. 450, or the reign of Isdigerd I. As usual the ground plan is an oblong square. [PLATE XXVI.] It is remarkable that the entire building had but a single entrance. This was by a noble arch, above 50 feet in height, which faced north, and gave admission into a vaulted hall, nearly 90 feet long by 43 wide, having at either side two lesser halls of a similar character, opening into it by somewhat low semi-circular arches, of nearly the full width of the apartments. Beyond these rooms, and communicating with them by narrow, but elegant doorways, were three domed chambers precisely similar, occupying together the full width of the building, each about 43 feet square, and crowned by elliptical domes rising to the height of nearly 70 feet. [PLATE XXVII., Fig. 1.] The ornamentation of these chambers was by their doorways, and by false windows, on the Persepolitan model. The domed chambers opened into some small apartments, beyond which was a large court, about 90 feet square, surrounded by vaulted rooms of various sizes, which for the most part communicated directly with it. False windows, or recesses, relieved the interior of these apartments, but were of a less elaborate character than those of the domed chambers. Externally the whole building was chastely and tastefully ornamented by the tall narrow arches and reed-like pilasters already mentioned. [PLATE XXVII., Fig. 2.] Its character, however, was upon the whole "simple and severe;" nor can we quarrel with the judgment which pronounces it "more like a gigantic bastile than the palace of a gay, pavilion-loving people like the Persians."

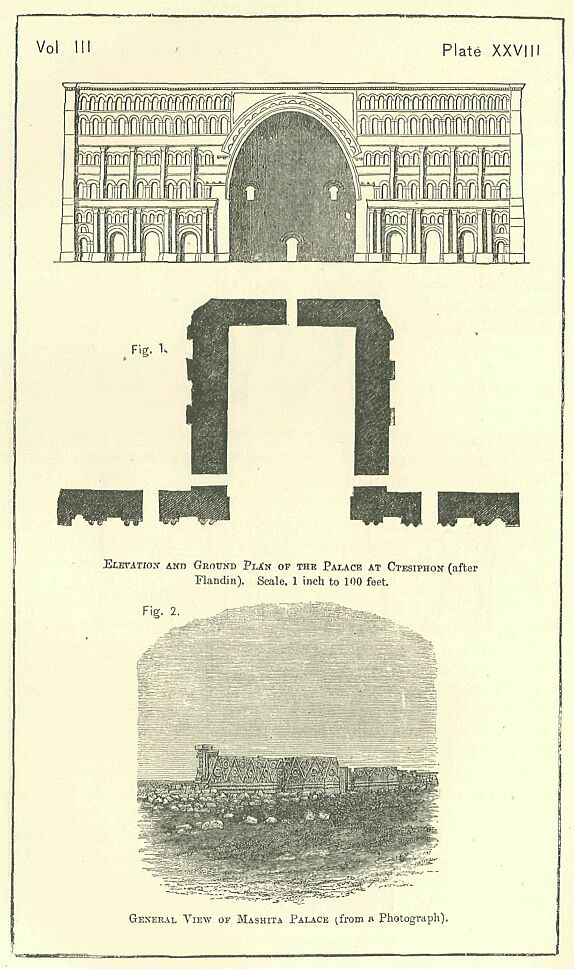

It is difficult to form any very decided opinion upon the architectural merits of the third and grandest of the Sassanian palaces, the well known "Takht-i-Ehosru," or palace of Chosroe's Anushirwan, at Ctesiphon. What remains of this massive erection is a mere fragment, which, to judge from the other extant Sassanian ruins, cannot have formed so much as one fourth part of the original edifice. [PLATE XXVIII., Fig. 1.] Nothing has come down to our day but a single vaulted hall on the grandest scale, 72 feet wide, 85 high, and 115 deep, together with the mere outer wall of what no doubt constituted the main facade of the building. The apartments, which, according to all analogy, must have existed at the two sides, and in the rear, of the great hall, some of which should have been vaulted, have wholly perished. Imagination may supply them from the Firuzabad, or the Mashita palace; but not a trace, even of their foundations, is extant; and the details, consequently, are uncertain, though the general plan can scarcely be doubted. At each side of the great hall were probably two lateral ones, communicating with each other, and capable of being entered either from the hall or from the outer air. Beyond the great hall was probably a domed chamber, equalling it in width, and opening upon a court, round which were a number of moderate-sized apartments. The entire building was no doubt an oblong square, of which the shorter sides seem to have measured 370 feet. It had at least three, and may not improbably have had a larger number of entrances, since it belongs to tranquil times and a secure locality.

The ornamentation of the existing facade of the palace is by doorways, doubly-arched recesses, pilasters, and string-courses. These last divide the building, externally, into an appearance of three or four distinct stories. The first and second stories are broken into portions by pilasters, which in the first or basement stories are in pairs, but in the second stand singly. It is remarkable that the pilasters of the second story are not arranged with any regard to those of the first, and are consequently in many cases not superimposed upon the lower pilasters. In the third and fourth stories there are no pilasters, the arched recesses being here continued without any interruption. Over the great arch of the central hall, a foiling of seventeen small semicircular arches constitutes a pleasing and unusual feature.

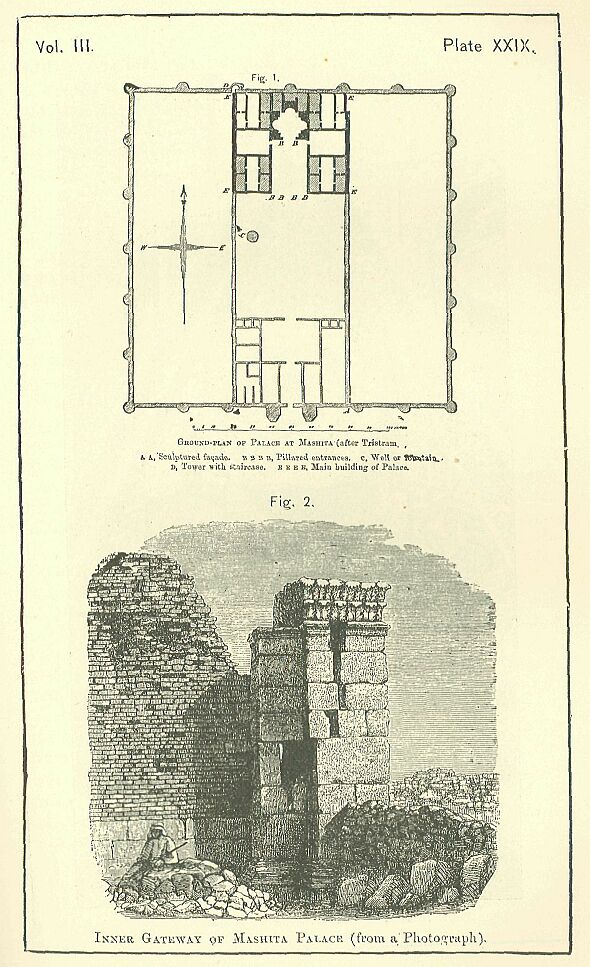

The Mashita palace, which was almost certainly built between A.D. 614 and A.D. 627, while on a smaller scale than that of Ctesiphon, was far more richly ornamented. [PLATE XXVIII., Fig. 2.] This construction of Chosroes II. (Parwiz) consisted of two distinct, buildings (separated by a court-yard, in which was a fountain), extending each of them about 180 feet along the front, with a depth respectively of 140 and 150 feet. The main building, which lay to the north, was entered from the courtyard by three archways, semicircular and standing side by side, separated only by columns of hard, white stone, of a quality approaching to marble. These columns were surmounted by debased Corinthian capitals, of a type introduced by Justinian, and supported arches which were very richly fluted, and which are said to have been "not unlike our own late Norman work." [PLATE XXIX., Fig. 2.] The archways gave entrance into an oblong court or hall, about 80 feet long, by sixty feet wide, on which opened by a wide doorway the main room of the building. This was a triapsal hall, built of brick, and surmounted by a massive domed roof of the same material, which rested on pendentives like those employed at Serbistan and at Firuzabad. The diameter of the hall was a little short of 60 feet. On either side of the triapsal hall, and in its rear, and again on either side of the court or hall on which it opened, were rooms of a smaller size, generally opening into each other, and arranged symmetrically, each side being the exact counterpart of the other. The number of these smaller apartments was twenty-five. [PLATE XXIX., Fig. 1.]

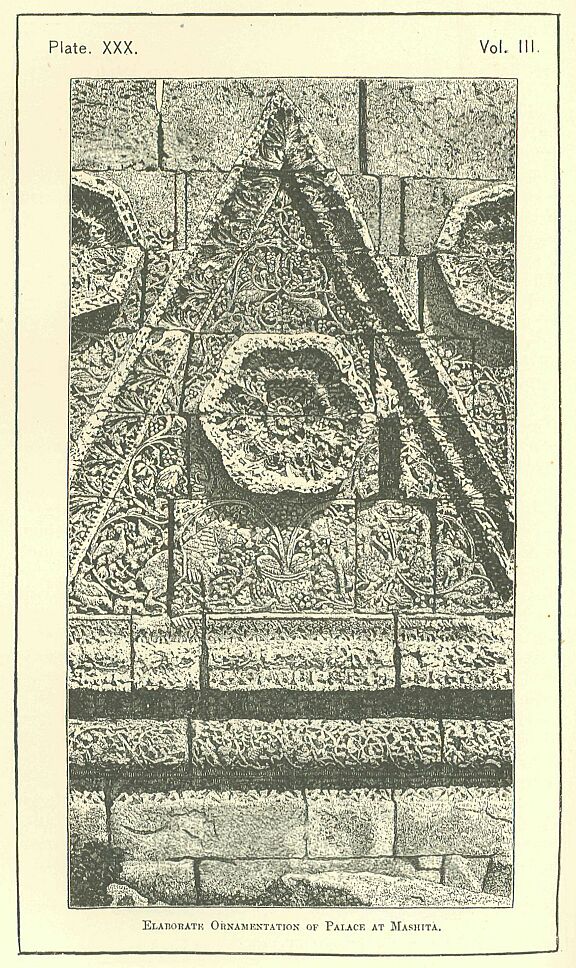

The other building, which lies towards the south, and is separated from the one just described by the whole length of the court-yard, a distance of nearly 200 feet, appears to have been for the most part of an inferior character. It comprised one large hall, or inner court, but otherwise contained only small apartments, which, it is thought, may have been "intended as guard-rooms for the soldiers." Although, however, in most respects so unpretending, this edifice was adorned externally with a richness and magnificence unparalleled in the other remains of Sassanian times, and scarcely exceeded in the architecture of any age or nation. Forming, as it did, the only entrance by which the palace could be approached, and possessing the only front which was presented to the gaze of the outer world, its ornamentation was clearly an object of Chosroes' special care, who seems to have lavished upon it all the known resources of art. The outer wall was built of finely-dressed hard stone; and on this excellent material the sculptors of the time—whether Persian or Byzantine, it is impossible to determine—proceeded to carve in the most elaborate way, first a bold pattern of zigzags and rosettes, and then, over the entire surface, a most delicate tracery of foliage, animals, and fruits. The effect of the zigzags is to divide the wall into a number of triangular compartments, each of which is treated separately, covered with a decoration peculiar to itself, a fretwork of the richest kind, in which animal and vegetable forms are most happily intermingled. In one a vase of an elegant shape stands midway in the triangle at its base; two doves are seated on it, back to back; from between them rises a vine, which spreads its luxuriant branches over the entire compartment, covering it with its graceful curves and abundant fruitage; on either side of the vase a lion and a wild boar confront the doves with a friendly air; while everywhere amid the leaves and grapes we see the forms of birds, half revealed, half hidden by the foliage. Among the birds, peacocks, parrots, and partridges have been recognized; among the beasts, besides lions and wild boars, buffaloes, panthers, lynxes, and gazelles. In another panel a winged lion, the "lineal descendant of those found at Nineveh and Persepolis," reflects the mythological symbolism of Assyria, and shows how tenacious was its hold on the West-Asian mind. Nor is the human form wholly wanting. In one place we perceive a man's head, in close juxtaposition with man's inseparable companion, the dog; in another, the entire figure of a man, who carries a basket of fruit.

Besides the compartments within the zigzags, the zigzags themselves and the rosettes are ornamented with a patterning of large leaves, while the moulding below the zigzags and the cornice, or string-course, above them are covered with conventional designs, the interstices between them being filled in with very beautiful adaptations of lesser vegetable forms.

Altogether, the ornamentation of this magnificent facade may be pronounced almost unrivalled for beauty and appropriateness; and the entire palace may well be called "a marvellous example of the sumptuousness and selfishness of ancient princes," who expended on the gratification of their own taste and love of display the riches which would have been better employed in the defence of their kingdoms, or in the relief of their poorer subjects.

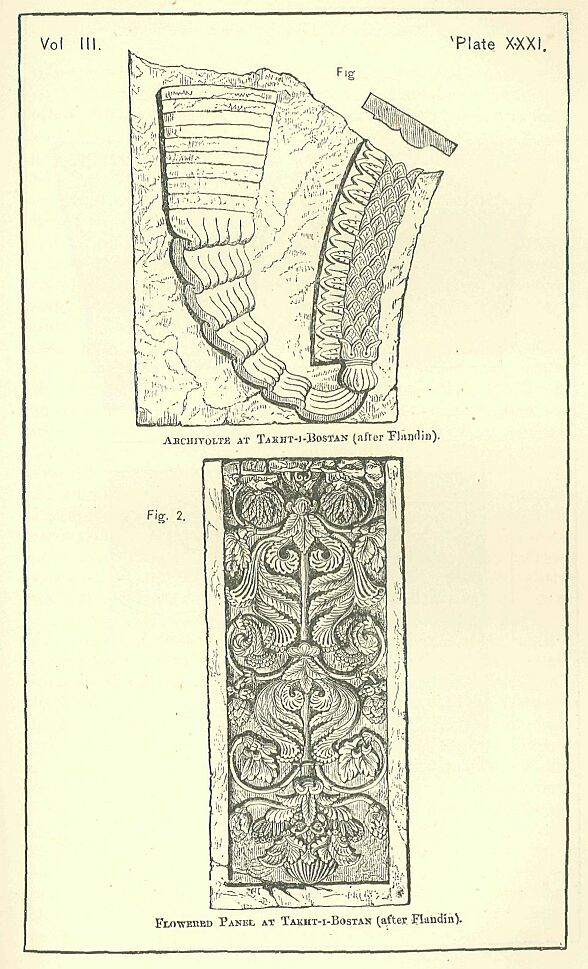

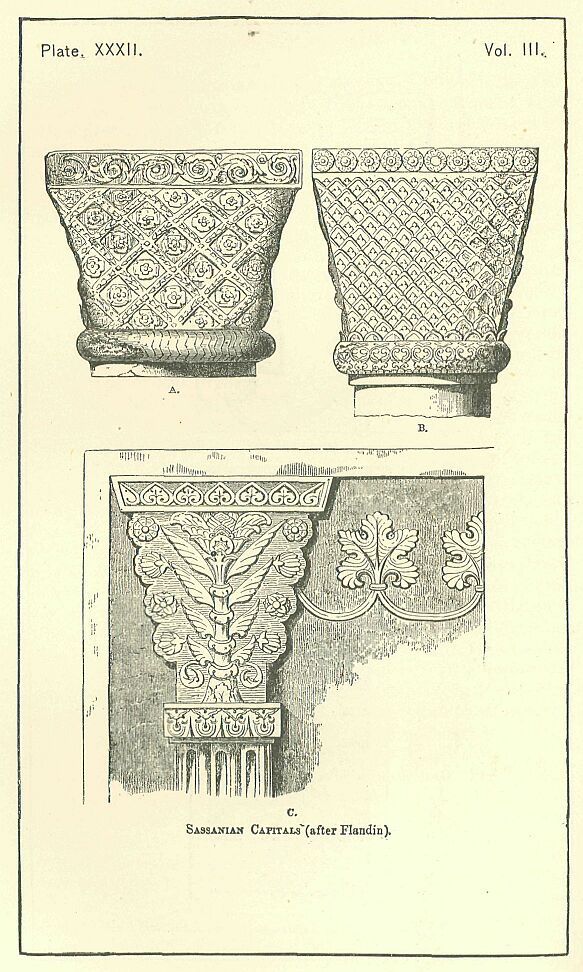

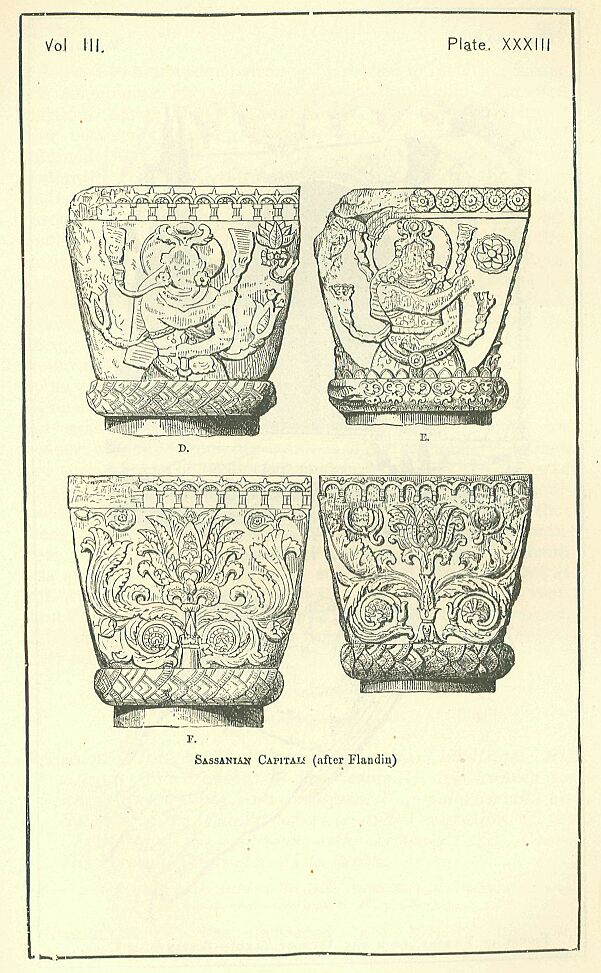

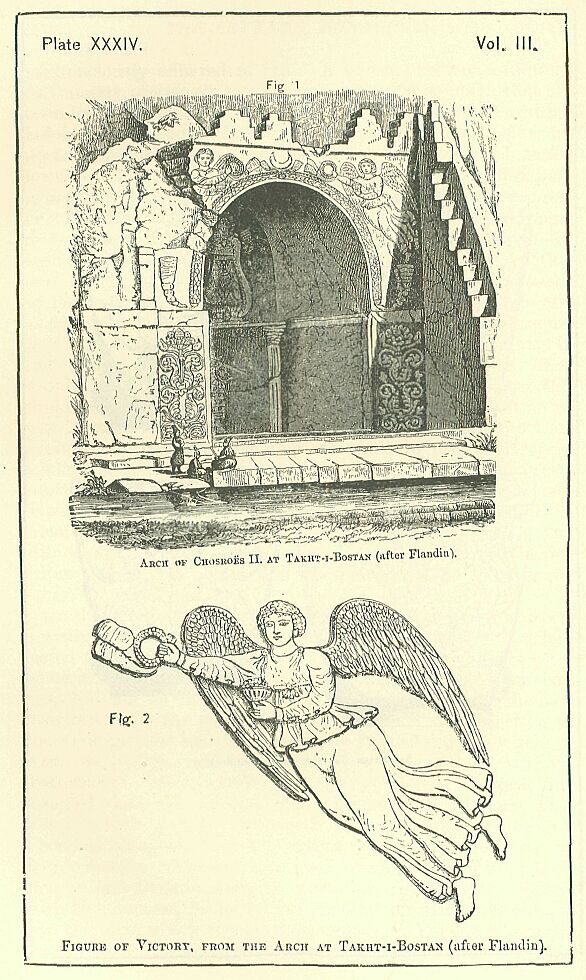

The exquisite ornamentation of the Mashita palace exceeds anything which is found elsewhere in the Sassanian buildings, but it is not wholly different in kind from that of other remains of their architecture in Media and Persia Proper. The archivolte which adorns the arch of Takht-i-Bostan [PLATE XXXI., Fig. 1.] possesses almost equal delicacy with the patterned cornice or string-course of the Mashita building; and its flowered panels may compare for beauty with the Mashita triangular compartments. [PLATE XXXI., Fig. 2.] Sassanian capitals are also in many instances of lovely design, sometimes delicately diapered (A, B), sometimes worked with a pattern of conventional leaves and flowers [PLATE XXXII.], occasionally exhibiting the human form (D, E), or a flowery patterning, like that of the Takht-i-Bostan (F, Q). [PLATE XXXIII.] In the more elaborate specimens, the four faces—for the capitals are square—present designs completely different; in other instances, two of the four faces are alike, but on the other two the design is varied. The shafts of Sassanian columns, so far as we can judge, appear to have been fluted.

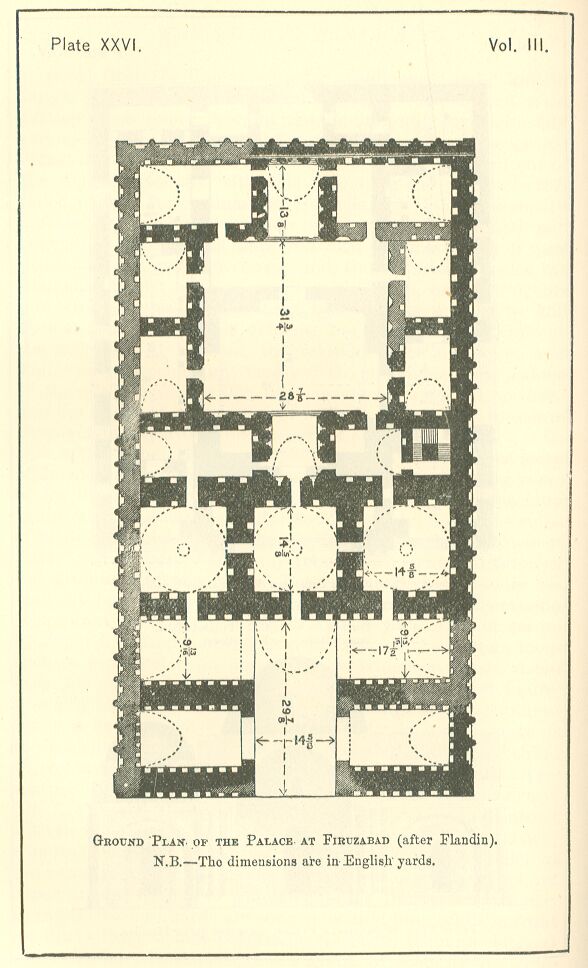

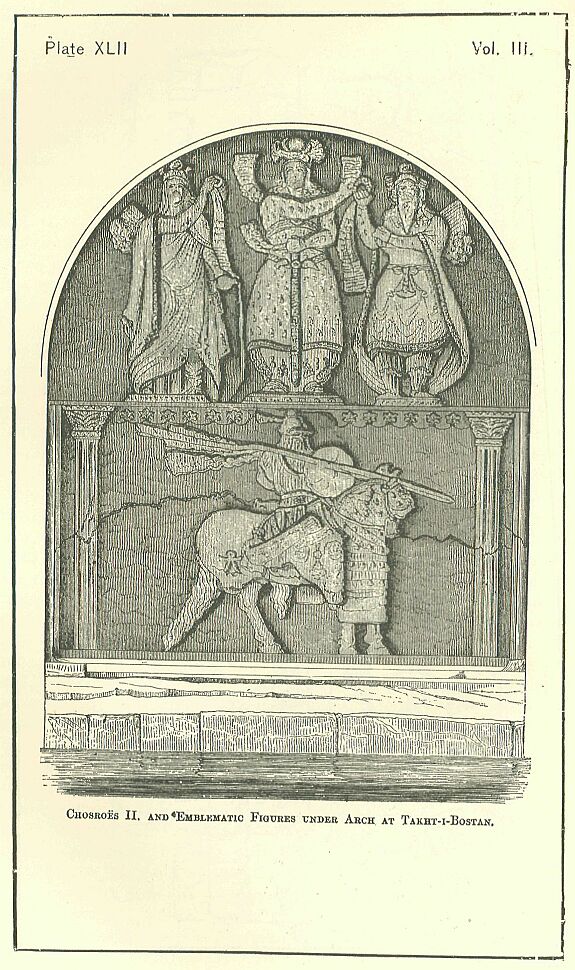

A work not exactly architectural, yet possessing architectural features—the well-known arch of Chosroes II. above alluded to—seems to deserve description before we pass to another branch of our subject. [PLATE XXXIV., Fig. 1.] This is an archway or grotto cut in the rock at Takht-i-Bostan, near Kerman-shah, which is extremely curious and interesting. On the brink of a pool of clear water, the sloping face of the rock has been cut into, and a recess formed, presenting at its further end a perpendicular face. This face, which is about 34 feet broad, by 31 feet high, and which is ornamented at the top by some rather rude gradines, has been penetrated by an arch, cut into the solid stone to the depth of above 20 feet, and elaborately ornamented, both within and without. Externally, the arch is in the first place surmounted by the archivolte already spoken of, and then, in the spandrels on either side are introduced flying figures of angels or Victories, holding chaplets in one hand and cups or vases in the other, which are little inferior to the best Roman art. [PLATE XXXIV., Fig. 2.] Between the figures is a crescent, perhaps originally enclosing a ball, and thus presenting to the spectator, at the culminating point of the whole sculpture, the familiar emblems of two of the national divinities. Below the spandrels and archivolte, on either side of the arched entrance, are the flowered panels above-mentioned, alike in most respects, but varying in some of their details. Within the recess, its two sides, and its further end, are decorated with bas-reliefs, those on the sides representing Chosroes engaged in the chase of the wild boar and the stag, while those at the end, which are in two lines, one over the other, show the monarch, above, in his robes of state, receiving wreaths from ideal beings; below, in his war costume, mounted upon his favorite charger, Sheb-Diz, with his spear poised in his hand, awaiting the approach of the enemy. The modern critic regards this figure as "original and interesting." We shall have occasion to recur to it when we treat of the "Manners and Customs" of the Neo-Persian people.

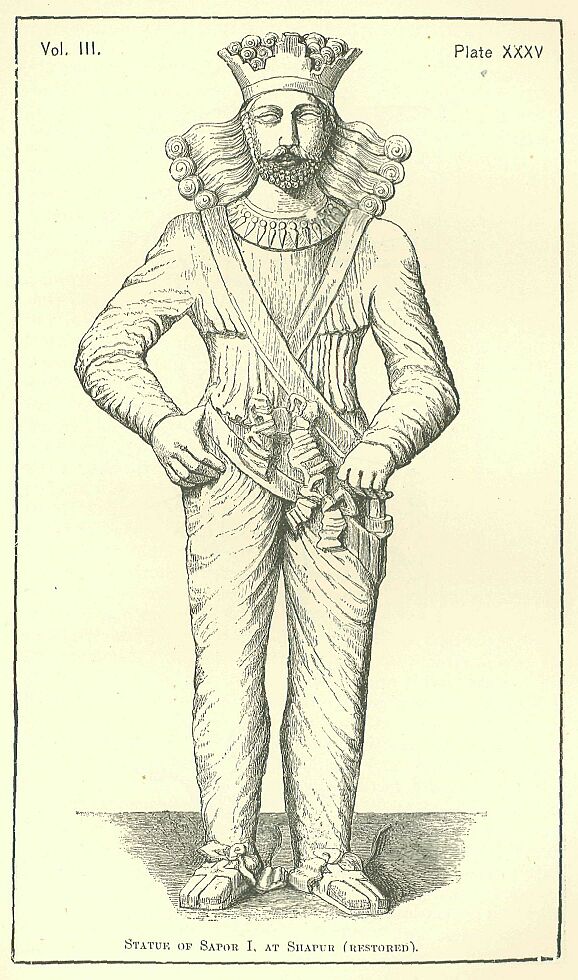

The glyptic art of the Sassanian is seen chiefly in their bas-reliefs; but one figure "in the round" has come down to us from their times, which seems to deserve particular description. This is a colossal statue of Sapor I., hewn (it would seem) out of the natural rock, which still exists, though overthrown and mutilated, in a natural grotto near the ruined city of Shapur. [PLATE XXXV.] The original height of the figure, according to M. Texier, was 6 metres 7 centimetres, or between 19 and. 20 feet. It was well proportioned, and carefully wrought, representing the monarch in peaceful attire, but with a long sword at his left side, wearing the mural crown which characterizes him on the bas-reliefs, and dressed in a tunic and trousers of a light and flexible material, apparently either silk or muslin. The hair, beard, and mustachios, were neatly arranged and well rendered. The attitude of the figure was natural and good. One hand, the right, rested upon the hip; the other touched, but without grasping it, the hilt of the long straight sword. If we may trust the representation of M. Texier's artist, the folds of the drapery were represented with much skill and delicacy; but the hands and feet of the figure, especially the latter, were somewhat roughly rendered.

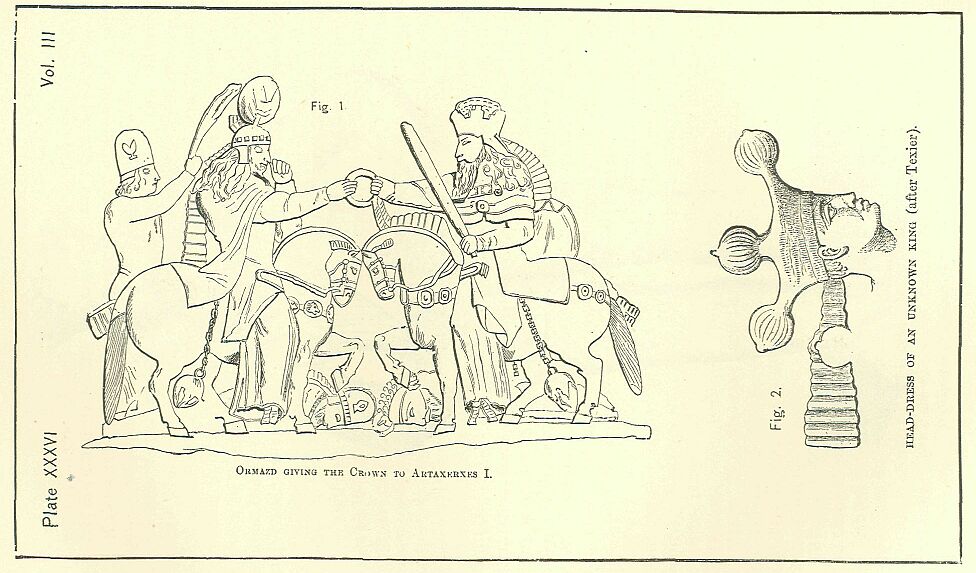

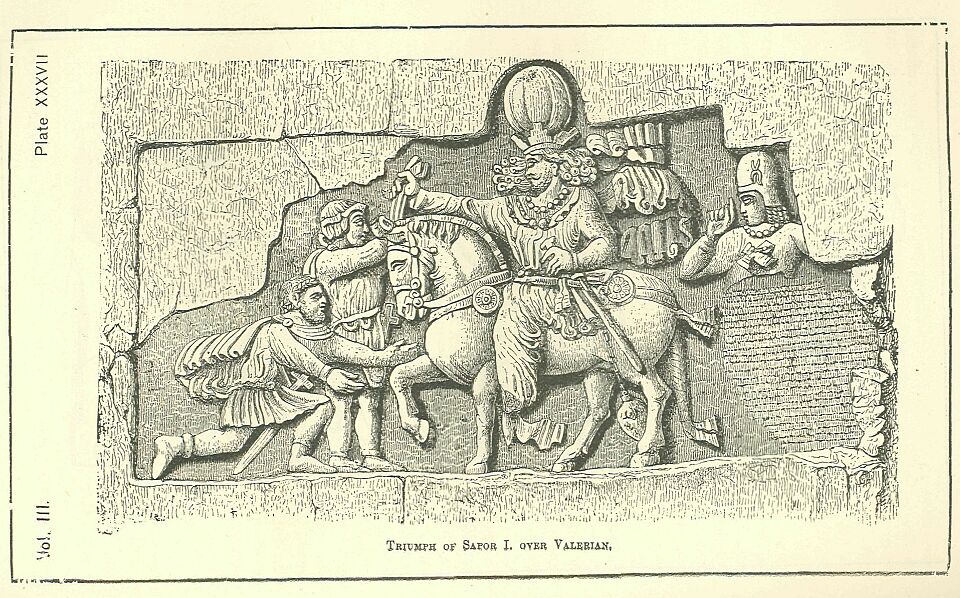

The bas-reliefs of the Sassanians are extremely numerous, and though generally rude, and sometimes even grotesque, are not without a certain amount of merit. Some of the earlier and coarser specimens have been already given in this volume; and one more of the same class is here appended [PLATE XXXVI., Fig. 1.] but we have now to notice some other and better examples, which seem to indicate that the Persians of this period attained a considerable proficiency in this branch of the glyptic art. The reliefs belonging to the time of Sapor I. are generally poor in conception and ill-executed; but in one instance, unless the modern artist has greatly flattered his original, a work of this time is not devoid of some artistic excellence. This is a representation of the triumph of Sapor over Valerian, comprising only four figures—Sapor, an attendant, and two Romans—of which the three principal are boldly drawn, in attitudes natural, yet effective, and in good proportion. [PLATE XXXVII.] The horse on which Sapor rides is of the usual clumsy description, reminding us of those which draw our brewers' wains; and the exaggerated hair, floating ribbons and uncouth head-dress of the monarch give an outre and ridiculous air to the chief figure; but, if we deduct these defects, which are common to almost all the Sassanian artists, the representation becomes pleasing and dignified. Sapor sits his horse well, and thinks not of himself, but of what he is doing. Cyriades, who is somewhat too short, receives the diadem from his benefactor with a calm satisfaction. But the best figure is that of the captive emperor, who kneels on one knee, and, with outstretched arms, implores the mercy of the conqueror. The whole representation is colossal, the figures being at least three times the size of life; the execution seems to have been good; but the work has been considerably injured by the effects of time.

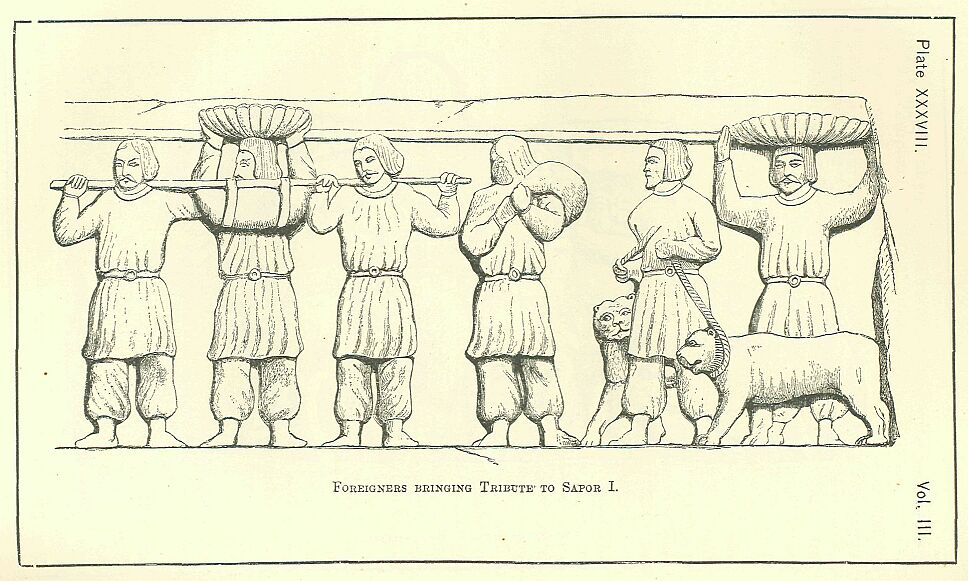

Another bas-relief of the age of Sapor I. is on too large a scale, and too complicated, to be represented here; but a description may be given of it, and a specimen subjoined, from which the reader may judge of its character. On a surface of rock at Shapur, carefully smoothed and prepared for sculpture, the second Sassanian monarch appears in the centre of the tablet, mounted on horseback, and in his usual costume, with a dead Roman under his horse's feet, and holding another (Cyriades?), by the hand. In front of him, a third Roman, the representative of the defeated nation, makes submission; and then follow thirteen tribute-bearers, bringing rings of gold, shawls, bowls, and the like, and conducting also a horse and an elephant. Behind the monarch, on the same line, are thirteen mounted guardsmen. Directly above, and directly below the central group, the tablet is blank; but on either side the subject is continued, above in two lines, and below in one, the guardsmen towards the left amounting in all to fifty-six, and the tribute-bearers on the right to thirty-five. The whole tablet comprises ninety-five human and sixty-three animal figures, besides a Victory floating in the sky. The illustration [PLATE XXXVIII.] is a representation of the extreme right-hand portion of the second line.

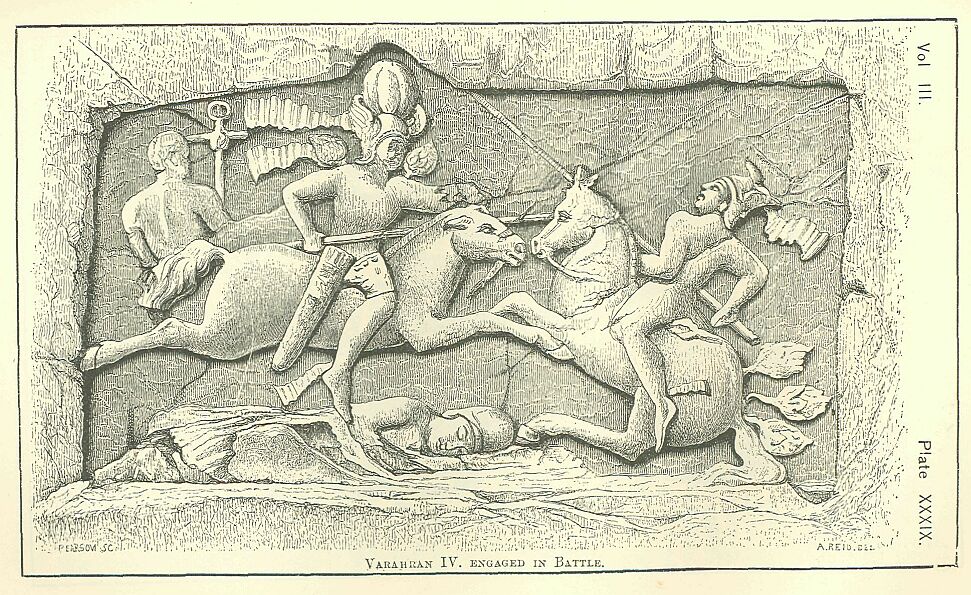

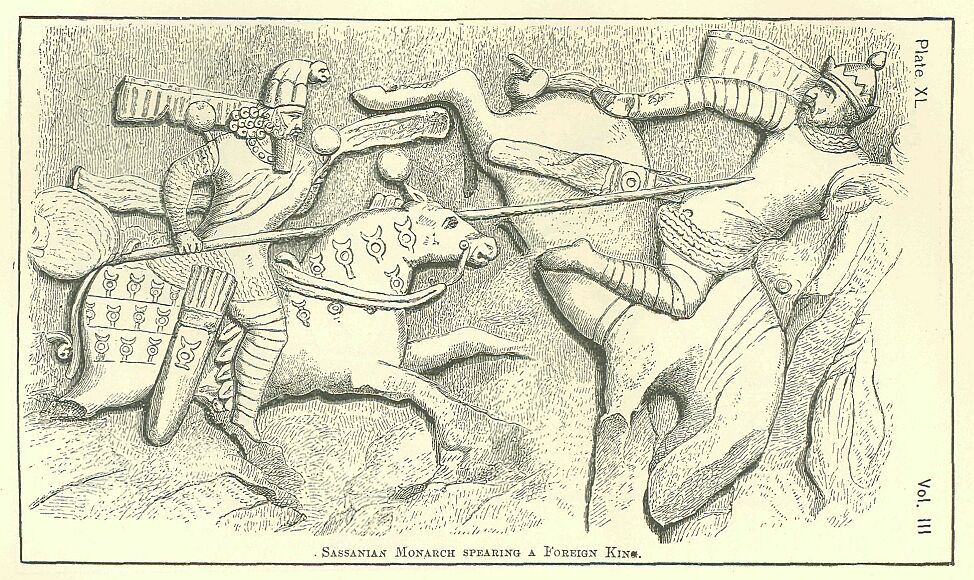

After the time of Sapor I. there is a manifest decline in Sassanian art. The reliefs of Varahran II. and Varahran III., of Narses and Sapor III., fall considerably below those of Sapor, son of Artaxerxes. It is not till we arrive at the time of Varahran IV. (A.D. 388-399) that we once more have works which possess real artistic merit. Indications have already appeared in an earlier chapter of this monarch's encouragement of artists, and of a kind of art really meriting the name. We saw that his gems were exquisitely cut, and embodied designs of first-rate excellence. It has now to be observed further, that among the bas-reliefs of the greatest merit which belong to Sassanian times, one at least must be ascribed to him; and that, this being so, there is considerable probability that two others of the same class belong also to his reign. The one which must undoubtedly be his, and which tends to fix the date of the other two, exists at Nakhsh-i-Kustam, near Persepolis, and has frequently been copied by travellers. It represents a mounted warrior, with the peculiar head-dress of Varahran IV., charging another at full speed, striking him with his spear, and bearing both horse and rider to the ground. [PLATE XXXIX.] A standard-bearer marches a little behind; and a dead warrior lies underneath Varahran's horse, which is clearing the obstacle in his bound. The spirit of the entire composition is admirable; and though the stone is in a state of advanced decay, travellers never fail to admire the vigor of the design and the life and movement which characterize it.

The other similar reliefs to which reference has been made exist, respectively, at Nakhsh-i-Eustam and at Firuzabad. The Nakhsh-i-Rustam tablet is almost a duplicate of the one above described and represented, differing from it mainly in the omission of the prostrate figure, in the forms of the head-dresses borne by the two cavaliers, and in the shape of the standard. It is also in better preservation than the other, and presents some additional details. The head-dress of the Sassanian warrior is very remarkable, being quite unlike any other known example. It consists of a cap, which spreads as it rises, and breaks into three points, terminating in large striped balls. [PLATE XXVI., Fig. 2.] His adversary wears a helmet crowned with a similar ball. The standard, which is in the form of a capital T, displays also five balls of the same sort, three rising from the cross-bar, and the other two hanging from it. Were it not for the head-dress of the principal figure, this sculpture might be confidently assigned to the monarch who set up the neighboring one. As it is, the point must be regarded as undecided, and the exact date of the relief as doubtful. It is, however, unlikely to be either much earlier, or much later, than the time of Varahran IV.

The third specimen of a Sassanian battle-scene exists at Firuzabad, in Persia Proper, and has been carefully rendered by M. Flandin. It is in exceedingly bad condition, but appears to have comprised the figures of either five or six horsemen, of whom the two principal are a warrior whose helmet terminates in the head of a bird, and one who wears a crown, above which rises a cap, surmounted by a ball. [PLATE XL.] The former of these, who is undoubtedly a Sassanian prince, pierces with his spear the right side of the latter, who is represented in the act of falling to the ground. His horse tumbles at the same time, though why he does so is not quite clear, since he has not been touched by the other charger. His attitude is extravagantly absurd, his hind feet being on a level with the head of his rider. Still more absurd seems to have been the attitude of a horse at the extreme right, which turns in falling, and exposes to the spectator the inside of the near thigh and the belly. But, notwithstanding these drawbacks, the representation has great merit. The figures live and breathe—that of the dying king expresses horror and helplessness, that of his pursuer determined purpose and manly strength. Even the very horses are alive, and manifestly rejoice in the strife. The entire work is full of movement, of variety, and of artistic spirit.

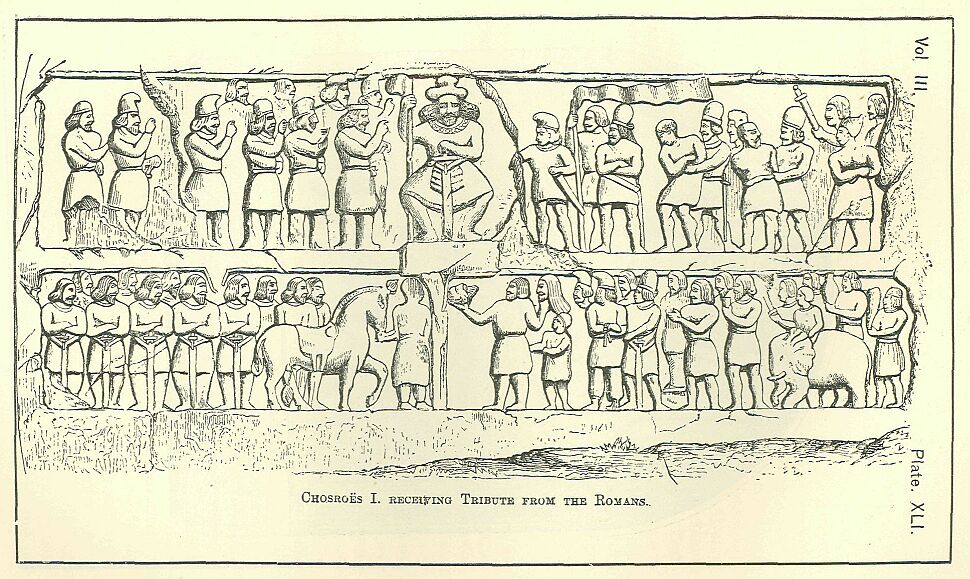

If we have regard to the highest qualities of glyptic art, Sassanian sculpture must be said here to culminate. There is a miserable falling off, when about a hundred and fifty years later the Great Chosroes (Anushirwan) represents himself at Shapur, seated on his throne, and fronting to the spectator, with guards and attendants on one side, and soldiers bringing in prisoners, human heads, and booty, on the other. [PLATE XLI.] The style here recalls that of the tamer reliefs set up by the first Sapor, but is less pleasing. Some of the prisoners appear to be well drawn; but the central figure, that of the monarch, is grotesque; the human heads are ghastly; and the soldiers and attendants have little merit. The animal forms are better—that of the elephant especially, though as compared with the men it is strangely out of proportion.

With Chosroes II. (Eberwiz or Parviz), the grandson of Anushirwan, who ascended the throne only twelve years after the death of his grandfather, and reigned from A.D. 591 to A.D. 628, a reaction set in. We have seen the splendor and good taste of his Mashita palace, the beauty of some of his coins, and the general excellence of his ornamentation. It remains to notice the character of his reliefs, found at present in one locality only, viz., at Takht-i-Bostan, where they constitute the main decorations of the great triumphal arch of this monarch. [PLATE XLII.]

These reliefs consist of two classes of works, colossal figures and hunting-pieces. The colossal figures, of which some account has been already given, and which are represented in PLATE XLI., have but little merit. They are curious on account of their careful elaboration, and furnish important information with respect to Sassanian dress and armature, but they are poor in design, being heavy, awkward, and ungainly. Nothing can well be less beautiful than the three overstout personages, who stand with their heads nearly or quite touching the crown of the arch, at its further extremity, carefully drawn in detail, but in outline little short of hideous. The least bad is that to the left, whose drapery is tolerably well arranged, and whose face, judging by what remains of it, was not unpleasing. Of the other two it is impossible to say a word in commendation.

The mounted cavalier below them—Chosroes himself on his black war horse, Sheb-Diz—is somewhat better. The pose of horse and horseman has dignity; the general proportions are fairly correct, though (as usual) the horse is of a breed that recalls the modern dray-horse rather than the charger. The figure, being near the ground, has suffered much mutilation, probably at the hands of Moslem fanatics; the off hind leg of the horse is gone; his nose and mouth have disappeared; and the horseman has lost his right foot and a portion of his lower clothing. But nevertheless, the general effect is not altogether destroyed. Modern travellers admire the repose and dignity of the composition, its combination of simplicity with detail, and the delicacy and finish of some portions. It may be added that the relief of the figure is high; the off legs of the horse were wholly detached; and the remainder of both horse and rider was nearly, though not quite, disengaged from the rock behind them.

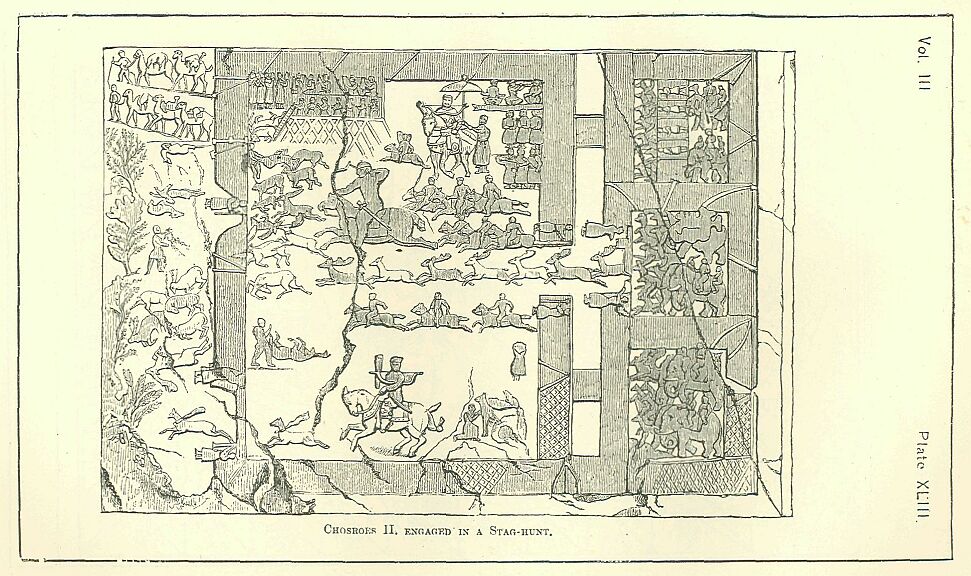

The hunting-pieces, which ornament the interior of the arched recess on either side, are far superior to the colossal figures, and merit an exact description. On the right, the perpendicular space below the spring of the arch contains the representation of a stag hunt, in which the monarch and about a dozen other mounted horsemen take part, assisted by some ten or twelve footmen, and by a detachment mounted on elephants. [PLATE XLIII.] The elephants, which are nine in number, occupy the extreme right of the tablet, and seem to be employed in driving the deer into certain prepared enclosures. Each of the beasts is guided by three riders, sitting along their backs, of whom the central one alone has the support of a saddle or howdah. The enclosures into which the elephants drive the game are three in number; they are surrounded by nets; and from the central one alone is there an exit. Through this exit, which is guarded by two footmen, the game passes into the central field, or main space of the sculpture, where the king awaits them. He is mounted on his steed, with his bow passed over his head, his sword at his side, and an attendant holding the royal parasol over him. It is not quite clear whether he himself does more than witness the chase. The game is in the main pursued and brought to the ground by horsemen without royal insignia, and is then passed over into a further compartment—the extreme one towards the left, where it is properly arranged and placed upon camels for conveyance to the royal palace. During the whole proceeding a band of twenty-six musicians, some of whom occupy an elevated platform, delights with a "concord of sweet sounds" the assembled sportsmen.

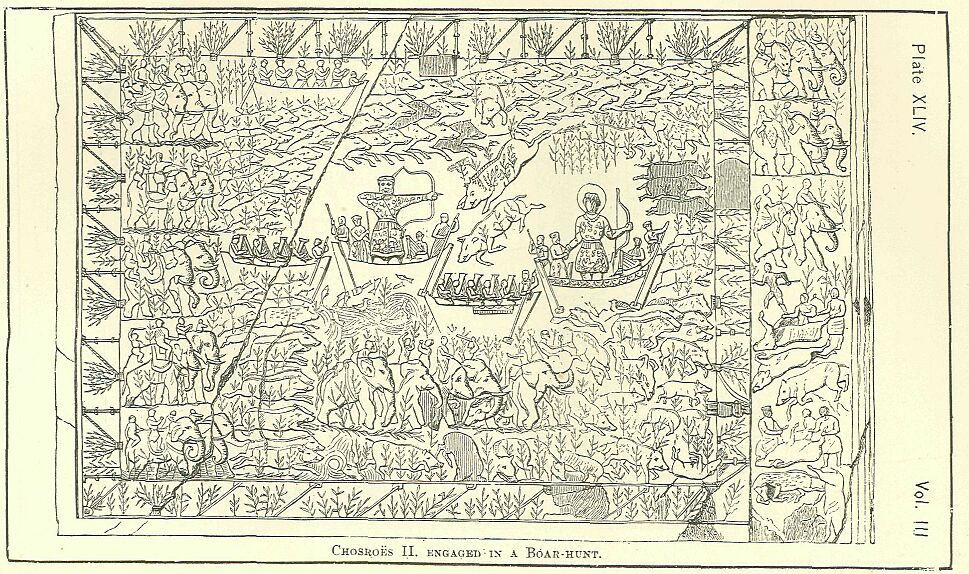

On the opposite, or left-hand, side of the recess, is represented a boar-hunt. [PLATE XLIV.] Here again, elephants, twelve in number, drive the game into an enclosure without exit. Within this space nearly a hundred boars and pigs may be counted. The ground being marshy, the monarch occupies a boat in the centre, and from this transfixes the game with his arrows. No one else takes part in the sport, unless it be the riders on a troop of five elephants, represented in the lower middle portion of the tablet. When the pigs fall, they are carried into a second enclosure, that on the right, where they are upturned, disembowelled, and placed across the backs of elephants, which convey them to the abode of the monarch. Once more, the scene is enlivened by music. Two bands of harpers occupy boats on either side of that which carries the king, while another harper sits with him in the boat from which he delivers his arrows. In the water about the boats are seen reeds, ducks, and numerous fishes. The oars by which the boats are propelled have a singular resemblance to those which are represented in some of the earliest Assyrian sculptures. Two other features must also be noticed. Near the top of the tablet, towards the left, five figures standing in a boat seem to be clapping their hands in order to drive the pigs towards the monarch; while in the right centre of the picture there is another boat, more highly ornamented than the rest, in which we seem to have a second representation of the king, differing from the first only in the fact that his arrow has flown, and that he is in the act of taking another arrow from an attendant In this second representation the king's head is surrounded by a nimbus or "glory." Altogether there are in this tablet more than seventy-five human and nearly 150 animal forms. In the other, the human forms are about seventy, and the animal ones about a hundred.

The merit of the two reliefs above described, which would require to be engraved on a large scale, in order that justice should be done to them, consists in the spirit and truth of the animal forms, elephants, camels, stags, boars, horses, and in the life and movement of the whole picture. The rush of the pigs, the bounds of the stags and hinds, the heavy march of the elephants, the ungainly movements of the camels, are well portrayed; and in one instance, the foreshortening of a horse, advancing diagonally, is respectably rendered. In general, Sassanian sculpture, like most delineative art in its infancy, affects merely the profile; but here, and in the overturned horse already described, and again in the Victories which ornament the spandrels of the arch of Chosroes, the mere profile is departed from with good effect, and a power is shown of drawing human and animal figures in front or at an angle. What is wanting in the entire Sassanian series is idealism, or the notion of elevating the representation in any respects above the object represented; the highest aim of the artist is to be true to nature; in this truthfulness is his triumph; but as he often falls short of his models, his whole result, even at the best, is unsatisfactory and disappointing.

Such must almost necessarily be the sentence of art critics, who judge the productions of this age and nation according to the abstract rules, or the accepted standards, of artistic effort. But if circumstances of time and country are taken into account, if comparison is limited to earlier and later attempts in the same region, or even in neighboring ones, a very much more favorable judgment will be passed. The Saseanian reliefs need not on the whole shrink from a comparison with those of the Achaemenian Persians. If they are ruder and more grotesque, they are also more spirited and more varied; and thus, though they fall short in some respects, still they must be pronounced superior to the Achaemenian in some of the most important artistic qualities. Nor do they fall greatly behind the earlier, and in many respects admirable, art of the Assyrians. They are less numerous and cover a lees variety of subjects; they have less delicacy; but they have equal or greater fire. In the judgment of a traveller not given to extravagant praise, they are, in some cases at any rate, "executed in the most masterly style." "I never saw," observes Sir R. Kerr Porter, "the elephant, the stag, or the boar portrayed with greater truth and spirit. The attempts at detailed human form are," he adds, "far inferior."

Before, however, we assign to the Sassanian monarchs, and to the people whom they governed, the merit of having produced results so worthy of admiration, it becomes necessary to inquire whether there is reason to believe that other than native artists wore employed in their production. It has been very confidently stated that Chosroes the Second "brought Roman artists" to Takht-i-Bostan, and by their aid eclipsed the glories of his great predecessors, Artaxerxes, son of Babek, and the two Sapors. Byzantine forms are declared to have been reproduced in the moldings of the Great Arch, and in the Victories. The lovely tracery of the Mashita Palace is regarded as in the main the work of Greeks and Syrians.06 No doubt it is quite possible that there may be some truth in these allegations; but we must not forget, or let it be forgotten, that they rest on conjecture and are without historical foundation. The works of the first Chosroes at Ctesiphon, according to a respectable Greek writer, were produced for him by foreign artists, sent to his court by Justinian. But no such statement is made with respect to his grandson. On the contrary, it is declared by the native writers that a certain Ferhad, a Persian, was the chief designer of them; and modern critics admit that his hand may perhaps be traced, not only at Takht-i-Bostan, but at the Mashita Palace also. If then the merit of the design is conceded to a native artist, we need not too curiously inquire the nationality of the workmen employed by him.

At the worst, should it be thought that Byzantine influence appears so plainly in the later Sassanian works, that Rome rather than Persia must be credited with the buildings and sculptures of both the first and the second Chosroes, still it will have to be allowed that the earlier palaces—those at Ser-bistan and Firuzabad—and the spirited battle-scenes above described, are wholly native; since they present no trace of any foreign element. But, it is in these battle-scenes, as already noticed, that the delineative art of the Sassanians culminates; and it may further be questioned whether the Firuzabad palace is not the finest specimen of their architecture, severe though it be in the character of its ornamentation; so that, even should we surrender the whole of the later works enough will still remain to show that the Sassanians, and the Persians of their day, had merit as artists and builders, a merit the more creditable to them inasmuch as for five centuries they had had no opportunity of cultivating their powers, having been crushed by the domination of a race singularly devoid of artistic aspirations. Even with regard to the works for which they may have been indebted to foreigners, it is to be remembered that, unless the monarchs had appreciated high art, and admired it, they would not have hired, at great expense, the services of these aliens. For my own part, I see no reason to doubt that the Sassanian remains of every period are predominantly, if not exclusively, native, not excepting those of the first Chosroes, for I mistrust the statement of Theophylact.