Civil War of Narses and his Brother Hormisdas. Narses victorious. He attacks and expels Tiridates. War declared against him by Diocletian. First Campaign of Galerius, A.D. 297. Second Campaign, A.D. 298. Defeat suffered by Narses. Negotiations. Conditions of Peace. Abdication and Death of Narses.

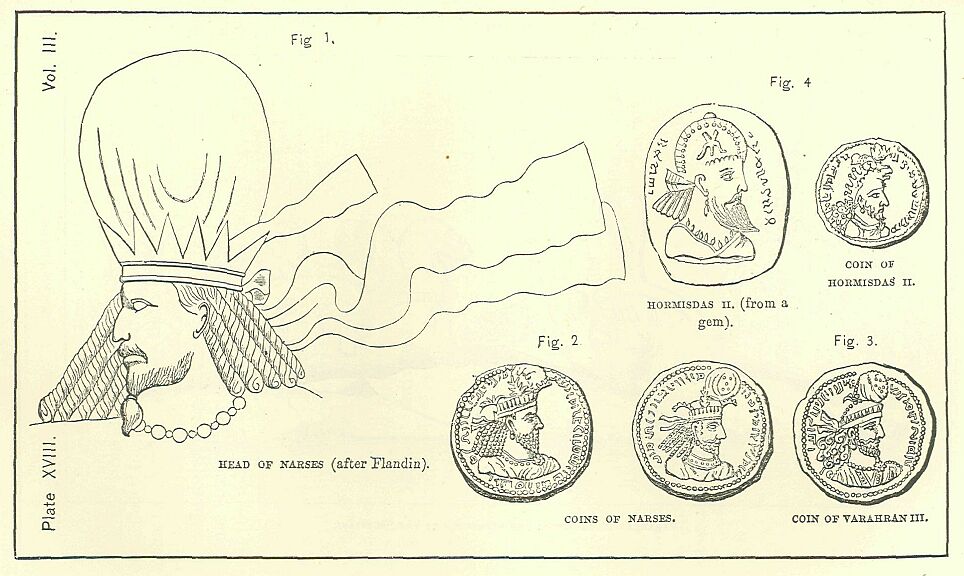

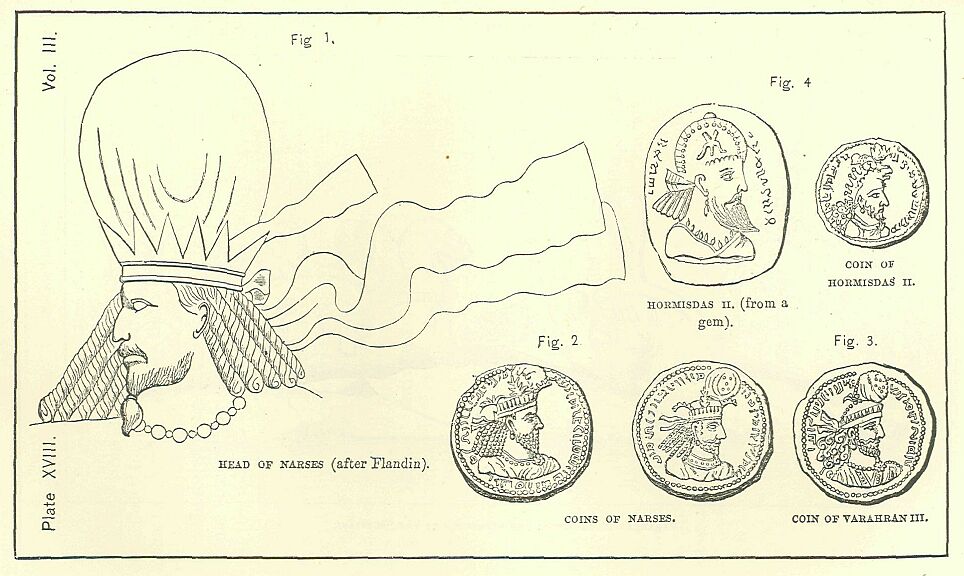

It appears that on the death of Varahran III., probably without issue, there was a contention for the crown between two brothers, Narses and Hormisdas. We are not informed which of them was the elder, nor on what grounds they respectively rested their claims; but it seems that Narses was from the first preferred by the Persians, and that his rival relied mainly for success on the arms of foreign barbarians. Worsted in encounters wherein none but Persians fought on either side, Hormisdas summoned to his aid the hordes of the north—Gelli from the shores of the Caspian, Scyths from the Oxus or the regions beyond, and Russians, now first mentioned by a classical writer. But the perilous attempt to settle a domestic struggle by the swords of foreigners was not destined on this occasion to prosper. Hormisdas failed in his endeavor to obtain the throne; and, as we hear no more of him, we may regard it as probable that he was defeated and slain. At any rate Narses was, within a year or two of his accession, so firmly settled in his kingdom that he was able to turn his thoughts to the external affairs of the empire, and to engage in a great war. All danger from internal disorder must have been pretty certainly removed before Narses could venture to affront, as he did, the strongest of existing military powers. [PLATE XVIII.]

Narses ascended the throne in A.D. 292 or 293. It was at least as early as A.D. 296 that he challenged Rome to an encounter by attacking in force the vassal monarch whom her arms had established in Armenia. Tiridates had, it is evident, done much to provoke the attack by his constant raids into Persian territory, which were sometimes carried even to the south of Ctesiphon. He was probably surprised by the sudden march and vigorous assault of an enemy whom he had learned to despise; and, feeling himself unable to organize an effectual resistance, he had recourse to flight, gave up Armenia to the Persians, and for a second time placed himself under the protection of the Roman emperor. The monarch who held this proud position was still Diocletian, the greatest emperor that had occupied the Roman throne since Trajan, and the prince to whom Tiridates was indebted for his restoration to his kingdom. It was impossible that Diocletian should submit to the affront put upon him without an earnest effort to avenge it. His own power rested, in a great measure, on his military prestige; and the unpunished insolence of a foreign king would have seriously endangered an authority not very firmly established. The position of Diocletian compelled him to declare war against Narses in the year A.D. 296, and to address himself to a struggle of which he is not likely to have misconceived the importance. It might have been expected that he would have undertaken the conduct of the war in person; but the internal condition of the empire was far from satisfactory, and the chief of the State seems to have felt that he could not conveniently quit his dominions to engage in war beyond his borders. He therefore committed the task of reinstating Tiridates and punishing Narses to his favorite and son-in-law, Galerius, while he himself took up a position within the limits of the empire, which at once enabled him to overawe his domestic adversaries and to support and countenance his lieutenant.

The first attempts of Galerius were unfortunate. Summoned suddenly from the Danube to the Euphrates, and placed at the head of an army composed chiefly of the levies of Asia, ill-disciplined, and unacquainted with their commander, he had to meet an adversary of whom he knew little or nothing, in a region the character of which was adverse to his own troops and favorable to those of the enemy. Narses had invaded the Roman province of Mesopotamia, had penetrated to the Khabour, and was threatening to cross the Euphrates into Syria. Galerius had no choice but to encounter him on the ground which he had chosen. Now, though Western Mesopotamia is ill-described as a smooth and barren surface of sandy desert, without a hillock, without a tree, and without a spring of fresh water, it is undoubtedly an open country, possessing numerous plains, where, in a battle, the advantage of numbers is likely to be felt, and where there is abundant room for the evolutions of cavalry. The Persians, like their predecessors the Parthians, were especially strong in horse; and the host which Narses had brought into the field greatly outnumbered the troops which Diocletian had placed at the disposal of Galerius. Yet Galerius took the offensive. Fighting under the eye of a somewhat stern master, he was scarcely free to choose his plan of campaign. Diocletian expected him to drive the Persians from Mesopotamia, and he was therefore bound to make the attempt. He accordingly sought out his adversary in this region, and engaged him in three great battles. The first and second appear to have been indecisive; but in the third the Roman general suffered a complete defeat. The catastrophe of Crassus was repeated almost upon the same battle-field, and probably almost by the same means. But, personally, Galerius was more fortunate than his predecessor. He escaped from the carnage, and, recrossing the Euphrates, rejoined his father-in-law in Syria. A conjecture, not altogether destitute of probability, makes Tiridates share both the calamity and the good fortune of the Roman Caesar. Like Galerius, he escaped from the battle-field, and reached the banks of the Euphrates. But his horse, which had received a wound, could not be trusted to pass the river. In this emergency the Armenian prince dismounted, and, armed as he was, plunged into the stream. The river was both wide and deep; the current was rapid; but the hardy adventurer, inured to danger and accustomed to every athletic exercise, swam across and reached the opposite bank in safety.

Thus, while the rank and file perished ignominiously, the two personages of most importance on the Roman side were saved. Galerius hastened towards Antioch, to rejoin his colleague and sovereign. The latter came out to meet him, but, instead of congratulating him on his escape, assumed the air of an offended master, and, declining to speak to him or to stop his chariot, forced the Caesar to follow him on foot for nearly a mile before he would condescend to receive his explanations and apologies for defeat. The disgrace was keenly felt, and was ultimately revenged upon the prince who had contrived it. But, at the time, its main effect doubtless was to awake in the young Caesar the strongest desire of retrieving his honor, and wiping out the memory of his great reverse by a yet more signal victory. Galerius did not cease through the winter of A.D. 297 to importune his father-in-law for an opportunity of redeeming the past and recovering his lost laurels.

The emperor, having sufficiently indulged his resentment, acceded to the wishes of his favorite. Galerius was continued in his command. A new army was collected during the winter, to replace that which had been lost; and the greatest care was taken that its material should be of good quality, and that it should be employed where it had the best chance of success. The veterans of Illyria and Moesia constituted the flower of the force now enrolled; and it was further strengthened by the addition of a body of Gothic auxiliaries. It was determined, moreover, that the attack should this time be made on the side of Armenia, where it was felt that the Romans would have the double advantage of a friendly country, and of one far more favorable for the movements of infantry than for those of an army whose strength lay in its horse. The number of the troops employed was still small. Galerius entered Armenia at the head of only 25,000 men; but they were a picked force, and they might be augmented, almost to any extent, by the national militia of the Armenians. He was now, moreover, as cautious as he had previously been rash; he advanced slowly, feeling his way; he even personally made reconnaissances, accompanied by only one or two horsemen, and, under the shelter of a flag of truce, explored the position of his adversary. Narses found himself overmatched alike in art and in force. He allowed himself to be surprised in his camp by his active enemy, and suffered a defeat by which he more than lost all the fruits of his former victory. Most of his army was destroyed; he himself received a wound, and with difficulty escaped by a hasty flight. Galerius pursued, and, though he did not succeed in taking the monarch himself, made prize of his wives, his sisters, and a number of his children, besides capturing his military chest. He also took many of the most illustrious Persians prisoners. How far he followed his flying adversary is uncertain; but it is scarcely probable that he proceeded much southward of the Armenian frontier. He had to reinstate Tiridates in his dominions, to recover Eastern Mesopotamia, and to lay his laurels at the feet of his colleague and master. It seems probable that having driven Narses from Armenia, and left Tiridates there to administer the government, he hastened to rejoin Diocletian before attempting any further conquests.

The Persian monarch, on his side, having recovered from his wound, which could have been but slight, set himself to collect another army, but at the same time sent an ambassador to to the camp of Galerius, requesting to know the terms on which Rome would consent to make peace. A writer of good authority has left us an account of the interview which followed between the envoy of the Persian monarch and the victorious Roman. Apharban (so was the envoy named) opened the negotiations with the following speech:

"The whole human race knows," he said, "that the Roman and Persian kingdoms resemble two great luminaries, and that, like a man's two eyes, they ought mutually to adorn and illustrate each other, and not in the extremity of their wrath to seek rather each other's destruction. So to act is not to act manfully, but is indicative rather of levity and weakness; for it is to suppose that our inferiors can never be of any service to us, and that therefore we had bettor get rid of them. Narses, moreover, ought not to be accounted a weaker prince than other Persian kings; thou hast indeed conquered him, but then thou surpassest all other monarchs; and thus Narses has of course been worsted by thee, though he is no whit inferior in merit to the best of his ancestors. The orders which my master has given me are to entrust all the rights of Persia to the clemency of Rome; and I therefore do not even bring with me any conditions of peace, since it is for the emperor to determine everything. I have only to pray, on my master's behalf, for the restoration of his wives and male children; if he receives them at your hands, he will be forever beholden to you, and will be better pleased than if he recovered them by force of arms. Even now my master cannot sufficiently thank you for the kind treatment which he hears you have vouchsafed them, in that you have offered them no insult, but have behaved towards them as though on the point of giving them back to their kith and kin. He sees herein that you bear in mind the changes of fortune and the instability of all human affairs."

At this point Galerius, who had listened with impatience to the long harangue, burst in with a movement of anger that shook his whole frame—"What? Do the Persians dare to remind us of the vicissitudes of fortune, as though we could forget how they behave when victory inclines to them? Is it not their wont to push their advantage to the uttermost and press as heavily as may be on the unfortunate? How charmingly they showed the moderation that becomes a victor in Valerian's time! They vanquished him by fraud; they kept him a prisoner to advanced old age; they let him die in dishonor; and then when he was dead they stripped off his skin, and with diabolical ingenuity made of a perishable human body an imperishable monument of our shame. Verily, if we follow this envoy's advice, and look to the changes of human affairs, we shall not be moved to clemency, but to anger, when we consider the past conduct of the Persians. If pity be shown them, if their requests be granted, it will not be for what they have urged, but because it is a principle of action with us—a principle handed down to us from our ancestors—to spare the humble and chastise the proud." Apharban, therefore, was dismissed with no definite answer to his question, what terms of peace Rome would require; but he was told to assure his master that Rome's clemency equalled her valor, and that it would not be long before he would receive a Roman envoy authorized to signify the Imperial pleasure, and to conclude a treaty with him.

Having held this interview with Apharban, Galerius hastened to meet and consult his colleague. Diocletian had remained in Syria, at the head of an army of observation, while Galerius penetrated into Armenia and engaged the forces of Persia. When he heard of his son-in-law's great victory he crossed the Euphrates, and advancing through Western Mesopotamia, from which the Persians probably retired, took up his residence at Nisibis, now the chief town of these parts. It is perhaps true that his object was "to moderate, by his presence and counsels, the pride of Galarius." That prince was bold to rashness, and nourished an excessive ambition. He is said to have at this time entertained a design of grasping at the conquest of the East, and to have even proposed to himself to reduce the Persian Empire into the form of a Roman province. But the views of Diocletian were humbler and more prudent. He held to the opinion of Augustus and Hadrian, that Rome did not need any enlargement of her territory, and that the absorption of the East was especially undesirable. When he and his son-in-law met and interchanged ideas at Nisibis, the views of the elder ruler naturally prevailed; and it was resolved to offer to the Persians tolerable terms of peace. A civilian of importance, Sicorius Probus, was selected for the delicate office of envoy, and was sent, with a train of attendants, into Media, where Narses had fixed his headquarters. We are told that the Persian monarch received him with all honor, but, under pretence of allowing him to rest and refresh himself after his long journey, deferred his audience from day to day; while he employed the time thus gained in collecting from various quarters such a number of detachments and garrisons as might constitute a respectable army. He had no intention of renewing the war, but he knew the weight which military preparation ever lends to the representations of diplomacy. Accordingly it was not until he had brought under the notice of Sicorius a force of no inconsiderable size that he at last admitted him to an interview. The Roman ambassador was introduced into an inner chamber of the royal palace in Media, where he found only the king and three others—Apharban, the envoy sent to Galerius, Archapetes, the captain of the guard, and Barsaborsus, the governor of a province on the Armenian frontier. He was asked to unfold the particulars of his message, and say what were the terms on which Rome would make peace. Sicorius complied. The emperors, he said, required five things:—(i.) The cession to Rome of five provinces beyond the river Tigris, which are given by one writer as Intilene, Sophene, Arzanene, Carduene, and Zabdicene; by another as Arzanene, Moxoene, Zabdicene, Rehimene, and Corduene; (ii.) the recognition of the Tigris, as the general boundary between the two empires; (iii.) the extension of Armenia to the fortress of Zintha, in Media; (iv.) the relinquishment by Persia to Rome of her protectorate over Iberia, including the right of giving investiture to the Iberian kings; and (v.) the recognition of Nisibis as the place at which alone commercial dealings could take place between the two nations.

It would seem that the Persians were surprised at the moderation of these demands. Their exact value and force will require some discussion; but at any rate it is clear that, under the circumstances, they were not felt to be excessive. Narses did not dispute any of them except the last: and it seems to have been rather because he did not wish it to be said that he had yielded everything, than because the condition was really very onerous, that he made objection in this instance. Sicorius was fortunately at liberty to yield the point. He at once withdrew the fifth article of the treaty, and, the other four being accepted, a formal peace was concluded between the two nations.

To understand the real character of the peace now made, and to appreciate properly the relations thereby established between Rome and Persia, it will be necessary to examine at some length the several conditions of the treaty, and to see exactly what was imported by each of them. There is scarcely one out of the whole number that carries its meaning plainly upon its face; and on the more important very various interpretations have been put, so that a discussion and settlement of some rather intricate points is here necessary.

(i.) There is a considerable difference of opinion as to the five provinces ceded to Rome by the first article of the treaty, as to their position and extent, and consequently as to their importance. By some they are put on the right, by others on the left, bank of the Tigris; while of those who assign them this latter position some place them in a cluster about the sources of the river, while others extend them very much further to the southward. Of the five provinces three only can be certainly named, since the authorities differ as to the two others. These three are Arzanene, Cordyene, and Zabdicene, which occur in that order in Patricius. If we can determine the position of these three, that of the others will follow, at least within certain limits.

Now Arzanene was certainly on the left bank of the Tigris. It adjoined Armenia, and is reasonably identified with the modern district of Kherzan, which lies between Lake Van and the Tigris, to the west of the Bitlis river. All the notices of Arzanene suit this locality; and the name "Kherzan" may be regarded as representing the ancient appellation.

Zabdicene was a little south and a little east of this position. It was the tract about a town known as Bezabda (perhaps a corruption of Beit-Zabda), which had been anciently called Phoenica. This town is almost certainly represented by the modern Fynyk, on the left bank of the Tigris, a little above Jezireh. The province whereof it was the capital may perhaps have adjoined Arzanene, reaching as far north as the Bitlis river.

If these two tracts are rightly placed, Cordyene must also be sought on the left bank of the Tigris. The word is no doubt the ancient representative of the modern Kurdistan, and means a country in which Kurds dwelt. Now Kurds seem to have been at one time the chief inhabitants of the Mons Masius, the modern Jebel Kara j ah Dagh and Jebel Tur, which was thence called Oordyene, Gordyene, or the Gordisean mountain chain. But there was another and a more important Cordyene on the opposite side of the river. The tract to this day known as Kurdistan, the high mountain region south and south-east of Lake Van between Persia and Mesopotamia, was in the possession of Kurds from before the time of Xenophon, and was known as the country of the Carduchi, as Cardyene, and as Cordyene. This tract, which was contiguous to Arzanene and Zabdicene, if we have rightly placed those regions, must almost certainly have been the Cordyene of the treaty, which, if it corresponded at all nearly in extent with the modern Kurdistan, must have been by far the largest and most important of the five provinces.

The two remaining tracts, whatever their names, must undoubtedly have lain on the same side of the Tigris with these three. As they are otherwise unknown to us (for Sophene, which had long been Roman, cannot have been one of them), it is impossible that they should have been of much importance. No doubt they helped to round off the Roman dominion in this quarter; but the great value of the entire cession lay in the acquisition of the large and fruitful province of Cordyene, inhabited by a brave and hardy population, and afterwards the seat of fifteen fortresses which brought the Roman dominion to the very edge of Adiabene, made them masters of the passes into Media, and laid the whole of Southern Mesopotamia open to their incursions. It is probable that the hold of Persia on the territory had never been strong; and in relinquishing it she may have imagined that she gave up no very great advantage; but in the hands of Rome Kurdistan became a standing menace to the Persian power, and we shall find that on the first opportunity the false step now taken was retrieved, Cordyene with its adjoining districts was pertinaciously demanded of the Romans, was grudgingly surrendered, and was then firmly re-attached to the Sassanian dominions.

(ii.) The Tigris is said by Patricius and Festus to have been made the boundary of the two empires. Gibbon here boldly substitutes the Western Khabour and maintains that "the Roman frontier traversed, but never followed, the course of the Tigris." He appears not to be able to understand how the Tigris could be the frontier, when five provinces across the Tigris were Roman. But the intention of the article probably was, first, to mark the complete cession to Rome of Eastern as well as Western Mesopotamia, and, secondly, to establish the Tigris as the line separating the empires below the point down to which the Romans held both banks. Cordyene may not have touch the Tigris at all, or may have touched it only about the 37th parallel. From this point southwards, as far as Mosul, or Nimrud, or possibly Kileh Sherghat, the Tigris was probably now recognized as the dividing line between the empires. By the letter of the treaty the whole Euphrates valley might indeed have been claimed by Rome; but practically she did not push her occupation of Mesopotamia below Circeshim. The real frontier from this point was the Mesopotamian desert, which extends from Kerkesiyeh to Nimrud, a distance of 150 miles. Above this it was the Tigris, as far probably as Feshapoor; after which it followed the line, whatever it was, which divided Oordyene from Assyria and Media.

(iii.) The extension of Armenia to the fortress of Zintha, in Media, seems to have imported much more than would at first sight appear from the words. Gibbon interprets it as implying the cession of all Media Atropatene, which certainly appears a little later to be in the possession of the Armenian monarch, Tiridates. A large addition to the Armenian territory out of the Median is doubtless intended; but it is quite impossible to determine definitely the extent or exact character of the cession.

(iv.) The fourth article of the treaty is sufficiently intelligible. So long as Armenia had been a fief of the Persian empire, it naturally belonged to Persia to exercise influence over the neighboring Iberia, which corresponded closely to the modern Georgia, intervening between Armenia and the Caucasus. Now, when Armenia had become a dependency of Rome, the protectorate hitherto exercised by the Sassanian princes passed naturally to the Caesars; and with the protectorate was bound up the right of granting investiture to the kingdom, whereby the protecting power was secured against the establishment on the throne of an unfriendly person. Iberia was not herself a state of much strength; but her power of opening or shutting the passes of the Caucasus gave her considerable importance, since by the admission of the Tatar hordes, which were always ready to pour in from the plains of the North, she could suddenly change the whole face of affairs in North-Western Asia, and inflict a terrible revenge on any enemy that had provoked her. It is true that she might also bring suffering on her friends, or even on herself, for the hordes, once admitted, were apt to make little distinction between friend and foe; but prudential considerations did not always prevail over the promptings of passion, and there had been occasions when, in spite of them, the gates had been thrown open and the barbarians invited to enter. It was well for Rome to have it in her power to check this peril. Her own strength and the tranquillity of her eastern provinces were confirmed and secured by the right which she (practically) obtained of nominating the Iberian monarchs.

(v.) The fifth article of the treaty, having been rejected by Narses and then withdrawn by Sicorius, need not detain us long. By limiting the commercial intercourse of the two nations to a single city, and that a city within their own dominions, the Romans would have obtained enormous commercial advantages. While their own merchants remained quietly at home, the foreign merchants would have had the trouble and expense of bringing their commodities to market a distance of sixty miles from the Persian frontier and of above a hundred from any considerable town; they would of course have been liable to market dues, which would have fallen wholly into Roman hands; and they would further have been chargeable with any duty, protective or even prohibitive, which Rome chose to impose. It is not surprising that Narses here made a stand, and insisted on commerce being left to flow in the broader channels which it had formed for itself in the course of ages.

Rome thus terminated her first period of struggle with the newly revived monarchy of Persia by a great victory and a great diplomatic success. If Narses regarded the terms—and by his conduct he would seem to have done so—as moderate under the circumstances, our conclusion must be that the disaster which he had suffered was extreme, and that he knew the strength of Persia to be, for the time, exhausted. Forced to relinquish his suzerainty over Armenia and Iberia, he saw those countries not merely wrested from himself, but placed under the protectorate, and so made to minister to the strength, of his rival. Nor was this all. Rome had gradually been advancing across Mesopotamia and working her way from the Euphrates to the Tigris. Narses had to acknowledge, in so many words, that the Tigris, and not the Euphrates, was to be regarded as her true boundary, and that nothing consequently was to be considered as Persian beyond the more eastern of the two rivers. Even this concession was not the last or the worst. Narses had finally to submit to see his empire dismembered, a portion of Media attached to Armenia, and five provinces, never hitherto in dispute, torn from Persia and added to the dominion of Rome. He had to allow Rome to establish herself in force on the left bank of the Tigris, and so to lay open to her assaults a great portion of his northern besides all his western frontier. He had to see her brought to the very edge of the Iranic plateau, and within a fortnight's march of Persia Proper. The ambition to rival his ancestor Sapor, if really entertained, was severely punished; and the defeated prince must have felt that he had been most ill-advised in making the venture.

Narses did not long continue on the throne after the conclusion of this disgraceful, though, it may be, necessary, treaty. It was made in A.D. 297. He abdicated in A.D. 301. It may have been disgust at his ill-success, it may have been mere weariness of absolute power, which caused him to descend from his high position and retire into private life. He was so fortunate as to have a son of full age in whose favor he could resign, so that there was no difficulty about the succession. His ministers seem to have thought it necessary to offer some opposition to his project; but their resistance was feeble, perhaps because they hoped that a young prince would be more entirely guided by their counsels. Narses was allowed to complete his act of self-renunciation, and, after crowning his son Hormisdas with his own hand, to spend the remainder of his days in retirement. According to the native writers, his main object was to contemplate death and prepare himself for it. In his youth he had evinced some levity of character, and had been noted for his devotion to games and to the chase; in his middle age he laid aside these pursuits, and, applying himself actively to business, was a good administrator, as well as a brave soldier. But at last it seemed to him that the only life worth living was the contemplative, and that the happiness of the hunter and the statesman must yield to that of the philosopher. It is doubtful how long he survived his resignation of the throne, but tolerably certain that he did not outlive his son and successor, who reigned less than eight years.